She Knows How to Work It: Madonna: Truth or Dare Turns 25

With the 25th anniversary of Madonna's underappreciated documentary, we take a look at what it means to be a "calculating" celebrity woman—then and now.

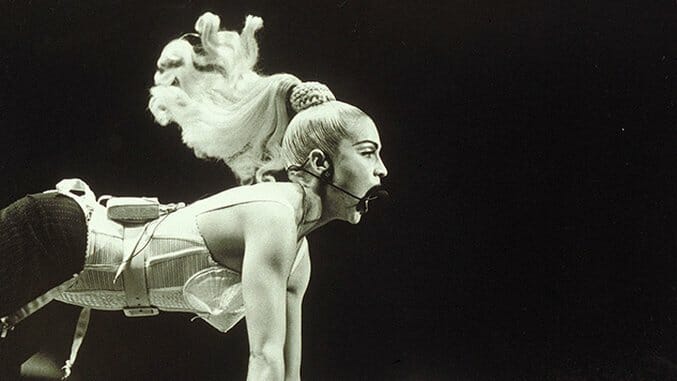

Twenty-five years ago this month, Madonna’s self-celebrating documentary Madonna: Truth or Dare was released. The film, which joins Madonna on her blockbuster 1990 Blonde Ambition tour, promised a “backstage” look at the world-famous pop star “as she really is,” but with its staged “confessions” and cheekily pretentious, black-and-white art-house style (likely an homage to D.A. Pennebaker’s famous Bob Dylan study Dont Look Back), Madonna: Truth or Dare challenged expectations.

It did not introduce audiences to a more down-to-earth star. It did not present a likable Madonna. Instead, Truth or Dare provided a portrait of Madonna the constant performer, at times abrasive and demanding, in control of every aspect of her career. Criticized upon its release for being “contrived” and “manipulated” by its subject—for its failure to reveal what audiences conceived to be a hidden “real Madonna”—the film is often gleefully phony. It is fascinating to watch for precisely the reason it was criticized—it is Madonna’s story told completely on Madonna’s terms, and challenges the idea of what is acceptably “real” when it comes to female celebrities.

What is “real,” and why is it something we expect of our pop icons?

Particularly when applied to female celebrities, it’s usually shorthand for down-to-earth and humble, describing an average person thrust into stardom, not one who instigates it. Kelly Clarkson is “real” because she was just a small-time Texas girl who won American Idol, while Lana del Rey is “fake” because she changed her image and gave herself a stage name in order to further her musical career. Personal crises also serve to make stars seem “real” by this definition—just look at the popularity of Jennifer Aniston and Jennifer Garner, two stars who suffered through public divorces and displayed emotional vulnerability in the press.

Being “real” usually translates to being “likable,” something against which Madonna has spent her career fighting. Yet, she still faces pressure to prove she is “real,” as do her successors in pop stardom, women like Beyoncé and Taylor Swift. What makes Madonna: Truth or Dare so compelling 25 years later is the way it subtly mocks this definition of “real,” extending a defiant middle finger into the face of “likability.”

It’s hard to remember now just how captivating a figure Madonna was in 1991, at the height of her music-bred fame, branching out into acting and keeping tabloid editors busy with her divorce from Sean Penn and subsequent romance with Warren Beatty. Known for unapologetically pushing boundaries of sexuality and exhibitionism, she was a woman constantly under a microscope. So, she decided to take that to its logical conclusion: Why not have cameras follow her around 24/7, recording her every dance rehearsal and bawdy backstage joke?

Madonna: Truth or Dare chronicles an especially grueling five-month tour at the height of Madonna’s international stardom (i.e., in her ice-blond, fake ponytail, underwear-over-clothing era). The film finds her at 32 years old, already a seasoned veteran of the music business and the pop-star life—she’s bossy, bitchy and funny, totally unafraid to show it. In Truth or Dare, we see Madonna as she sees herself, and the documentary highlights what she feels is important, not what someone else wants to reveal about her. In turn, director Alek Kesheshian takes an obviously hands-off approach, capturing a Madonna that is ultimately in charge of her image, her team and the documentary itself, bossing him around when he’s not actively deferring to her. In even the film’s final shot, Madonna hollers, “Cut it, Alek, goddamn it!”

Mixing on stage performances with backstage drama—Madonna bonding with her exuberant team of male dancers, joking with her brother Christopher, yelling at various members of the tech crew, lounging in glamorous robes and speaking directly to the camera in “confessional” portions—Madonna doesn’t hesitate to incorporate her personal life into all she does. Whether she’s dragging a recalcitrant Warren Beatty before the camera, meeting somewhat awkwardly with her father, or dishing with friend Sandra Bernhard, she rarely comes across as particularly “nice” or “likable,” preferring to be provocative above all. Madonna’s flippant attitude toward personal matters is captured in an exchange with Bernhard:

Madonna: I had those dreams when my mother died. For like a five-year period after that, that’s all I dreamed about—that people were jumping on me and strangling me. And I was constantly screaming for my father, and no sound would come out.

Bernhard: What happened when you woke up? You were crying?

Madonna: I’d be sweating and afraid and have to go sleep with my father.

Bernhard: Was that before he got remarried? How was that when you slept with him?

Madonna: Fine. I went right to sleep after he fucked me. [Laughter] I’m just kidding!

She can’t resist disrupting a moment of sincerity, upending the expectation that she recount her childhood trauma on camera. She does this throughout Truth or Dare, joking about deeply personal matters and then attempting to refocus the film’s attention on the rigors of the tour, which is clearly what she believes to be more important.

Truth or Dare’s central concern, then, is not to accurately depict Madonna’s personal relationships, but to showcase the pop star as the boss, a role that, in 1991, many did not see her inhabiting.

She was still often characterized as a provocateur with little substance, a performer whose creative output was the product of producers and hired professionals. In Truth or Dare she’s still very much the provocateur, but she’s also the prickly professional, demanding and exacting, sweating it out on stage night after night alongside a crew that obviously looks to her as their leader. Roger Ebert, who gave the film a positive review, praised its focus on the work of pop stardom, writing, “The organizing subject of the whole film is work. We learn a lot about how hard Madonna works, about her methods for working with her dancers and her backstage support team, about how brutally hard it is to do a world concert tour.” The film’s emphasis on Madonna’s intentionality is plainly stated on camera by one of her dancers: “She knows what she’s doing and she knows how to work it and that’s what’s important. That’s why she’s such a big star.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-