The fog that envelops Inherent Vice might bring to mind the old expression “thick as pea soup.” But that’s not quite right. Sometimes it’s like cotton candy, at others like ominous smoke. Paul Thomas Anderson’s drug-fueled detective odyssey depicts the end of the 1960s in a way that’s both mournful and madcap; coherency isn’t a priority—or even intended—in this tale of an era of endless possibilities coming to a close.

Anderson’s adaptation of Thomas Pynchon’s 2009 novel is both unnervingly surreal and pliably, affably keen to take every detour possible on the road from A to B. While its gags are ingenious and plentiful, heady themes rise from the madness: some good for laughs—the culture war is at the forefront of the story, and Anderson isn’t beneath milking a chocolate-covered banana’s phallic qualities as a hippie-hating authority figure devours it—and some, sometimes the very same themes, conjure up a distinct melancholy in the same breath, as in how the ideal of free love gives way to disturbing sexual dynamics.

Anderson delves into the stoned haze of the era, and of course, when drugs are involved, there are side effects. Anderson’s past films have always breathed precision: whether he indulged in the stylistic bravado of Punch Drunk Love and Boogie Nights, or stewed with the quieter brilliance of The Master and There Will Be Blood, each film, and each scene, carried an overarching purpose, even if they may have been initially puzzling. Here, the lack of a point sometimes is the point, which lends the film an aimless aura much more than any of Anderson’s past work. It can be frustrating at times, but one thing Anderson never is? Boring.

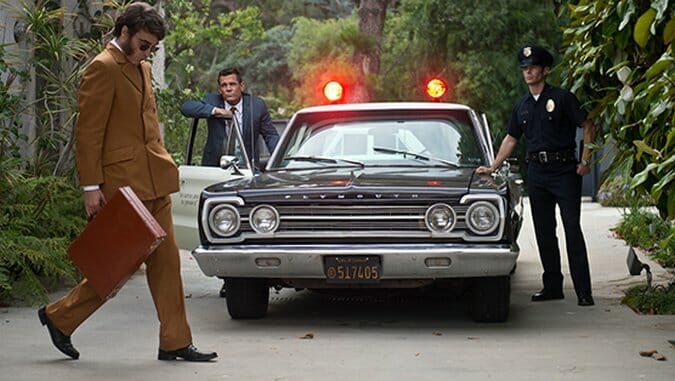

An attempt to summarize the plot would be just that: an attempt—and even then there’s no guarantee how clear it would be. Joaquin Phoenix stars as Doc Sportello, a burn-out private investigator trying to locate: 1) a potentially kidnapped billionaire; 2) that billionaire’s missing bodyguard; 3) a missing saxophone player; and 4) Doc’s own ex-girlfriend, who initiated the investigation in the first place. Phoenix plays the part with a mastery of facial manipulation, a breezy and casual physicality that belies his impeccable comic timing. Each scene is one more way to exploit Phoenix’s presence; take, for example, simply the way he walks to avoid abusive police officers, which provides one of the funniest moments of the year in film.

Anderson is clearly in love with the source text, incorporating sections of Pynchon’s writing into narration by Joanna Newsom. Yet he also has his actors deliver Pynchon’s stylized dialogue with a relaxed naturalism. As such, the words blend in quite well with the film’s smoky atmosphere, while simultaneously undermining the importance of actually understanding what they’re saying as our roadmap through the plot’s many nuances. The implied message: sit back and enjoy the ride.

And what a ride it is. We encounter “black power” groups, shady FBI agents, government informants, prostitutes and other staples of the era as Doc unravels layer upon layer of his investigation. In any traditional mystery story, the mystery itself becomes clearer as the puzzle pieces connect, leading our detective hero from one illuminating clue to another. In Inherent Vice, it’s as if three different jigsaw puzzles were thrown into a box together. Tangents rule the day, as new information presents itself only to be contradicted and confused. An entity called the Golden Fang, which Doc identifies as a unifying key to his many mysteries, morphs from a smuggling boat to a sinister crime syndicate to some sort of dental organization. Just when it seems like the group’s sinister dealings will be revealed, the film delivers a cocaine-fueled comedic vignette with an insane performance by Martin Short.

Anderson carefully introduces characters and plot points, then almost immediately, and religiously, subverts what he’s done. One subtle example is when we greet Tariq Khalil (Michael Kenneth Williams), who arrives at Doc’s office to provide exposition for the first of many sub-mysteries. The camera observes the character from an awkwardly low angle, suggesting a sort of domineering quality. Then Tariq sits down, the camera tilts with him, and suddenly we have a traditional straight-on shot without any expressionistic baggage. It’s consequently unclear what to expect of the character, and, by extension, what to expect from the film—and it simultaneously resembles a low-budget Blaxploitation cut, suggesting that even the film itself is unstable, bound to change at any moment, for any reason.

The characters are made all the more slippery due to the sheer number of them (along with their tendency to drift out of the story for long stretches—that is, if they appear more than once). Anderson hasn’t dealt with such a wide array of characters since 1999’s Magnolia, but that films told multiple, intercut stories with remarkable efficiency. Inherent Vice ostensibly tracks one dense, convoluted one, and its goal isn’t clarity or efficiency whatsoever, but to embrace the confusion.

So Phoenix is our guide, our constant, throughout this shifting landscape. The only other recurring face is Josh Brolin’s, who provides a fantastic foil to Doc as nemesis Bigfoot Bjornsen. Former actor turned LAPD poster boy, Bigfoot despises Doc and the drug-using, order-threatening culture he represents. Yet, while they dislike each other, their clashing personalities are also a source of comfort. It’s one of the few things they can each rely upon on. And similarly, their dynamic grounds the swirling plots that surround them: in both their animosity and dependence, Anderson finds the film’s anchor.

The title references an insurance term used on items that have a built-in instability that somehow causes the items to destroy themselves. Pynchon surely saw such an instability in the whole of ‘60s culture, whose anti-establishment ethos may have been too laid-back and too high to bring about anything but its own demise. Inherent Vice shares that instability: always in flux, it perseveres as a screwball elegy to a lost time, refusing to function solely as a stoner comedy or a serious drama or any one thing for that matter. Anderson is mannered enough to shift from one tone to another organically, making the whole seem part of one larger kaleidoscopic feeling rather than a series of disjointed vignettes, and that alone is a huge accomplishment. That he also characteristically includes a series of unforgettable scenes makes this film one that must be seen again, if not to better understand it, then to remember the sweet feeling of reveling in its haze.

Director: Paul Thomas Anderson

Writer: Paul Thomas Anderson, based on the book by Thomas Pynchon

Starring: Joaquin Phoenix, Josh Brolin, Benicio Del Toro, Jena Malone, Owen Wilson, Sasha Pieterse, Martin Short, Maya Rudolph, Katherine Waterston, Reese Witherspoon

Release Date: December 12, 2014