Can I Get a Witness: I Am Not Your Negro Gives the Race Problem Back to White American Film Critics

Movies Features James Baldwin

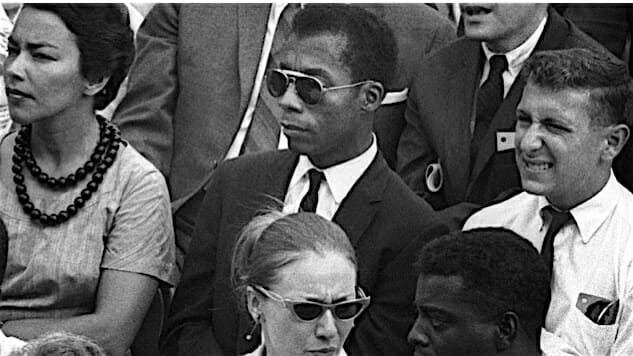

It’s rare that an artist is celebrated for an unfinished work. One has to be a Picasso, a Woolf or a Shakur to have built up enough of an audience so that even an incomplete work is worthy of great attention. James Baldwin falls into this category, as one of the most sought-after voices (past and present) for issues concerning race (and many other things) in America.

In 2017, filmmaker Raoul Peck presents an unfinished work of Baldwin’s as a visual essay with I Am Not Your Negro, in an attempt to pose lingering questions from the great writer’s time. I wanted to say that he does this because Baldwin isn’t here to do it himself … but isn’t he? I Am Not Your Negro sure makes it feel like one of the world’s most compelling minds is still here with us, still angry and still giving the so-called race problem back to its source: white America.

Black America did not invent slavery, Jim Crow, the school-to-prison pipeline, Ferguson or the Flint Water crisis; black America did not assassinate Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X (in spite of the optics) or Medgar Evers, all within the span of five years.

And black America did not “invent the nigger.”

In 2017, Peck and Baldwin want to know why so many of those who did invent such things have yet to admit that they did, and furthermore have yet to explain why they invented it. Why did you need to invent the nigger? When Baldwin poses the question, he poses it to white America. But re-stated in I Am Not Your Negro—a stylistically distinctive documentary with particular concern for American cinema—the question seems to beg a response from a group of people who might be just as unwilling to answer it as the general white public—white film critics.

First, it must be acknowledged that it’s no simple task for anyone to write about Peck’s film, in part because anything you may want to say about the film, you realize, you are saying about Baldwin himself. The documentary is presented using solely the words of James Baldwin, either via televised interviews and debates, or words narrated for the film, taken from the unpublished manuscript sent to his literary agent in 1979, “Notes Toward Remember This House.” How do you write about I Am Not Your Negro the film, without creating a piece that reads as merely in favor of, or against the ideas of James Baldwin? But something that must be considered alongside this question of the critic’s problem is that Peck’s decision to not include the perspectives and interpretations of others is a decision against distraction. When you refuse any intellectual analysis, celebrity commentary or fanfare—people telling you what Baldwin meant and how he meant it—what’s left? What do we see, or, rather, witness (a very important word for Baldwin)? What truths are unveiled when we let a great mind from the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s speak for itself in 2017?

Peck formally demands that we not only sit with Baldwin’s words, but that we engage with them, and respond. So how is it that not a single white film critic has responded to the most powerful and poignant question posed by Baldwin in a 1963 interview, and re-presented by Peck today?

Now here in this country we’ve got something called a nigger. It doesn’t in such terms exist in any other country in the world. We have invented the nigger. I didn’t invent him. White people invented him. I’ve always known and I had to know by the time I was 17 years old, what you were describing was not me, and what you were afraid of was not me. It had to be something else. You had invented it, so it had to be something you were afraid of … I’ve always known—and really, always, that’s part of the agony—I’ve always known that I’m not a nigger. But if I am not the nigger, and if it’s true that your invention reveals you, then who is the nigger?

You still think, I gather, that the nigger is necessary. But it’s unnecessary to me, so it must be necessary to you. So I give you your problem back. You’re the nigger, baby. It isn’t me. —James Baldwin

“Critics are those who have failed in art and literature,” said Benjamin Disraeli hundreds of years ago, and while many have since proven him false, there remains the belief that those who cannot create great works of art themselves are often destined to merely respond to and explain how greatness happens. One could argue that there remains, for example, a lack of interactive creativity between filmmaker and film writer, and similarly, a lack of interactive activism between the documentarian and his critic.

Something about I Am Not Your Negro offers up a chance for critics to do more. But so far as I can see, they have failed to embrace this opportunity. White critics in particular have all managed to ignore the most pressing message of the film. They have refused to acknowledge, let alone answer, the question given back to white audiences. Who is the nigger in modern-day America? Why is the nigger still necessary?

The argument here will of course be that it’s not a critic’s job to respond to political questions posed by subjects of a documentary. And I don’t mean to say that critics haven’t done their job—they have. Matt Zoller Seitz for Roger Ebert.com appropriately declares that I Am Not Your Negro is “a film that bears witness to a writer bearing witness.” For The Guardian, Jordan Hoffman writes a moving review, describing Peck’s work as “a cinematic séance, and one of the best movies about the civil rights era ever made.” The New Yorker’s Richard Brody says, “Peck’s references to current events reveal Baldwin’s view of history and his prophetic visions to be painfully accurate.” It appears that the film is beloved by practically all. “From the French New Wave-y opening credits, to editor Alexandra Strauss’ dynamic way of inserting startling posters and dozens of splendid film clips stretching from King Kong, Stagecoach and Dance, Fools, Dance to Elephant,” gushes Deborah Young of The Hollywood Reporter, “there is much to visually enjoy.”

But the film isn’t just here for us to enjoy, nor is it here for us to simply experience a baptism of Baldwin’s words over our collective consciousnesses. There is work to do, and the critic is not immune. So while many have done their jobs, I can’t help but feel that the job description must change, if only for this film, and for this moment.

I Am Not Your Negro, framed by this unwritten work of Baldwin’s, celebrates the incomplete, but perhaps it also tasks us with finishing, or working towards resolutions to the narrative Baldwin began so many years ago. Otherwise, what’s the point? Owen Gleiberman of Variety, who describes the film as “the rare movie that might be called a spiritual documentary,” is that rare critic willing to address his own personal biases towards Baldwin’s words. He admits to being jolted by what feels like pessimism from Baldwin, concerning “the Negro” problem. He finds himself, a white man, wondering why Baldwin told Dick Cavett that the problem might indeed be “hopeless.” Gleiberman is also willing to go further than other critics, admitting in the end that although there’s a feeling of being uplifted by Baldwin’s words, watching the film is “to feel cleansed, but warned. It’s to feel that the fire is here.” I agree that there is a warning here—a warning not to look away from the difficult parts, including this lingering question.

In 2017, as the veil of white supremacy in America is being lifted, I don’t believe it’s enough to simply write about a film like I Am Not Your Negro, and not push oneself beyond traditional styles of review. Can white film writers even ask themselves why they’ve no desire to sit with this question: why is it necessary to have a nigger? (I can hear them now: “But I do not need a nigger!”—as incredulous as all of the whites in America who insisted, “But I didn’t vote for Trump!”—as if they didn’t come from a world of people who did, as if a vote for Clinton absolved them of any and all possibilities of racism.)

And if such questions feel too big, why can’t film critics—particularly white critics—really ask themselves why this film is relevant today? Why are you, in this moment, writing down the word “Negro,” as if that is not a strange thing? It should be enough to shock you into some sort of fury—to shock you into writing something that transcends the film review and leaps into the political and social arenas, where it belongs. The question isn’t only, Why are you writing the word ‘Negro,’ but also, Do you want to still be writing that word, ten years from now? Will you have done the world, and future film critics a disservice if the words of I Am Not Your Negro still ring true in a decade?

Other, more difficult questions might be, “What do you, white film critics, gain, from such a word, still needing to be written down? And what are you, white film critics, willing to lose (because you would have to lose quite a lot—maybe even everything, depending on how you define yourself in this world, and how you are defined), so that such a word, such a thing as a negro, a nigger, may not need to exist as it currently does—in film or anywhere else?

I charge the critics with these tasks because I Am Not Your Negro also demands that we critique popular images in film and TV, which work to define our culture. Baldwin rages against the trope of the kind and noble black man: Sidney Poitier, and Hollywood’s insistence on reassuring white people that black people do not hate them. Listening to him, it occurs to me that in 2016 we had, for the first time, Oscar-contending movies with black characters who were neither supporting, uplifting or being uplifted or affirmed by white characters. In two major Hollywood productions, we saw black characters firmly set in black worlds. I Am Not Your Negro falls in line with them, in many ways, as a film disinterested in bringing pleasure to white audiences, figuring out white people, or offering up white heroes.

But Baldwin’s constant interrogation of pop culture suggests that it’s not enough to accept the “success” of such stories finally making it to the big screen and being met with critical acclaim. What few may have been willing to address, in their high praise of Moonlight, Fences and I Am Not Your Negro is that none of these stories would even exist if white America hadn’t insisted on having a nigger. Without white supremacy, we wouldn’t have neighborhoods in Miami, like the one Chiron grows up in (like Liberty City, where Moonlight director Barry Jenkins and playwright Tarell Alvin McCraney both grew up). Baseball players turned garbage collectors wouldn’t exist as they do in August Wilson’s Fences, and characters like Troy Maxson, performed by Denzel Washington, wouldn’t tell tales of battles with the Grim Reaper if white people hadn’t insisted on having niggers. If, in 2017, in this moment in history you only exalt the films and filmmakers, but refuse to think about the strangeness, and the irony in the name Liberty City, or refuse to think about what it took for you to finally see and thoughtfully review a film with an all-black cast, from a black director, then you are not performing this job to its full potential. You are seeing these films, but you are not a witness to their stories.

You cannot lynch me and keep me in ghettos without becoming something monstrous yourselves. And furthermore, you give me a terrifying advantage: you never had to look at me; I had to look at you. I know more about you than you know about me. Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.—James Baldwin

Most would agree that I Am Not Your Negro is the right film to have come along right now, though it’s not only because of the Black Lives Matter movement or because of Donald Trump winning the American presidency. Something like Syria, where an estimated 400,000 people have been killed, has, hopefully, left many of us changed. We will never again look back in history, wondering at how a Holocaust could have been achieved, with the whole world watching. But many of us will wonder about our place, as witnesses to a violent, ongoing catastrophe.

Baldwin himself struggled with the fact that he knew he was not meant to be on the front lines of a war. He wasn’t at every protest, he wasn’t beaten by cops, thrown in jail repeatedly, spat on at lunch counters, or lynched like so many of his brothers and sisters. Instead, he called himself a “witness.” He served his purpose, and even to this day, continues to serve. He was no Martin Luther King Jr., no Malcolm X, no Medgar Evers. But he bore witness to the lives, times and deaths of these Civil Rights icons, and so many others, and in that witnessing he became an icon himself. And I am Not Your Negro is concerned with the power of the audience, the witnesses, because Peck knows all too well that witnessing is no passive act.

I’m not putting it to white film critics to witness, so as to become icons. I’m wondering aloud if they might have the daring to witness, so as to come face to face with the real issues and questions of race and racism in Hollywood and beyond (so as to face the monstrous beings that might await them, in their very own reflections). We do not need more critics—especially white film critics—seeing films—especially films concerned with race in America—reviewing them, and then moving on with their lives, as if such stories were not a matter of life and death for some of us. In 2017 and beyond, we need film witnesses who are willing to step into the fire.

Otherwise, what are you here for?