Anyone who’s remotely familiar with filmmaker Ken Loach will know what to expect from The Old Oak. The performances, from a mix of non-actors and professionals, are variable; documentary-flavored scenes of characters gathered in rooms to argue and bluntly state their passions oscillate between stimulating and didactic; and a tone of oftentimes grave seriousness is occasionally punctured by scenes of such earnestness they border on the saccharine. If anything distinguishes the 27th feature by the grand old social realist of British cinema from the rest of his filmography, it’s that The Old Oak has the quiet, contemplative melancholy of a late work. If we’re to take Loach at his word, this movie will be his last.

Always at his strongest when he has a clear target at which to direct a righteous anger, Loach—who last teased retirement following the release of his 2014 period drama Jimmy’s Hall—has been lately re-energized by social and political turbulence in Britain under its recent series of Conservative governments. But where the two previous films in Loach’s unofficial state-of-the-nation trilogy, I, Daniel Blake and Sorry We Missed You, were bursts of fury, The Old Oak is a relative sigh. Though still a damning portrait of a country that has delivered its poor to the free market, The Old Oak is a comparatively gentle, reflective and even tentatively hopeful work.

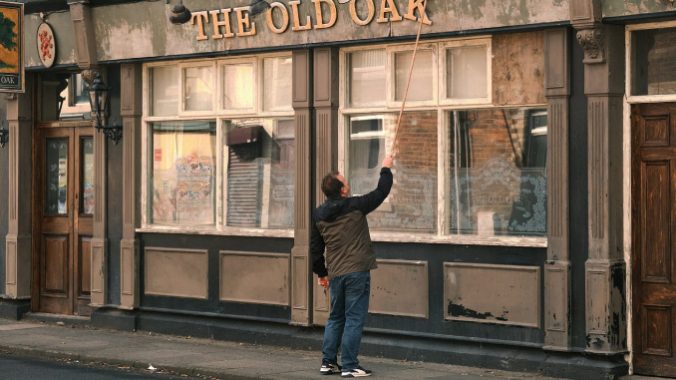

The Old Oak begins in 2016, the year of Britain’s fateful EU referendum, as a rundown former mining village in England’s North East is made a temporary home to a group of Syrian refugees. After clashing with some hostile locals for taking their picture, refugee and aspiring photographer Yara (Ebla Mari) is befriended by TJ Ballantyne (Dave Turner), owner of the film’s titular pub. A lapsed trade union firebrand, TJ is coaxed by Yara into reopening the long-closed back room of The Old Oak for a community feast, with the aim of uniting the village natives and their new neighbors.

Narrower in scope than Loach’s two previous broadsides against Tory rule, The Old Oak nods to wider problems—refugees fleeing conflict in the Middle East, the domestic earthquake of Brexit—but this time less space is given to forensically examining U.K. government policy and its deleterious effects on society. Instead, Loach and his regular screenwriter Paul Laverty keep the focus on The Old Oak’s divided village and its inhabitants’ hesitant path to unity.

With streets that are cluttered with rubbish and seemingly lawless—in addition to the many unchallenged instances of racist abuse directed at Yara and her family, at one point a beloved neighborhood dog is mauled to death by a ferocious pit bull, with no repercussions—the village feels more akin to a frontier town than a part of modern Britain. Loach rarely takes the action out of the village, making the isolation of the setting all the more pronounced, while also lending the film’s petty small-town dramas and their eventual resolutions that much more weight.

Aside from the misstep of giving TJ a history of suicidal ideation, something that plays like an unnecessary attempt to inject higher stakes into the film, The Old Oak is content to remain small; the antagonists are local bigots who want to keep the newcomers out of the pub, the film’s single most dramatic development involves a burst water pipe, and the big character arc is TJ’s journey from indifferent publican to the kind of community-minded organizer he used to be back in the village’s heyday.

It’s hard not to see parallels between Loach and TJ, an old rabble-rouser who can’t help advocating for social justice even as the landscape changes and his customers dwindle to a loyal few. Loach began his career in the 1960s, when as many as a quarter of people in Britain would tune in to watch his issue-led, documentary-style TV plays, and he has—up to the age of 87—continued to make issue-led, documentary-style movies even though those have long since become an arthouse concern. It seems that Loach is taking stock with The Old Oak, asking what impact a kitchen sink filmmaker like him might even still have in 2024, and ultimately deciding that, regardless, he’s going to tell stories his way.

There is in one sense a feeling of resignation to The Old Oak, with Loach still finding the need to address issues he’s addressed before in a number of other films (the British government’s disinterest in the welfare of its industrial towns and war’s tendency to displace innocent people, to name two). Of all Loach’s work, though, The Old Oak is most reminiscent of Jimmy’s Hall, and 10 years after that similarly minor “last film” about a well-loved community hub, Loach has reached the same conclusion: The world is set up to be hard for many, but it can be made a little easier when those people choose to unite. If The Old Oak really is Loach’s final film, that’s a bittersweet and, yes, overly-simplistic parting message, but it’s a comfortingly familiar one from a director who has been unshakably consistent over six decades.

Director: Ken Loach

Writer: Paul Laverty

Starring: Ebla Mari, Dave Turner

Release Date: April 5, 2024

Brogan Morris is a London-based freelance writer and editor, whose writing on film can also be found at the BFI, The Guardian, BBC Culture and more. You can follow him on X formerly known as Twitter at @BroganJMorris.