The hero would be no hero if death held for him any terror. … The hero … after his death, is still a synthesizing image: like Charlemagne, he sleeps only and will arise in the hour of destiny, or he is among us in another form. – The Hero with a Thousand Faces, by Joseph Campbell

From a few relatively small quarters, there is a great lot of dissatisfied howling over Star Wars Episode VIII: The Last Jedi. Director Rian Johnson took the film to a few places the saga has never been to before, and any film with a runtime that stretches past 150 minutes is going to start to warp under the force of its own gravity. The one area which seems to unite a lot of fan disappointment—including, it must be noted, even some naysaying from Mark Hamill—is Luke Skywalker.

But he hasn’t, not really (and he proves it in a way I found spellbinding). There are moments in the film that were hard to watch for people who have grown up on Luke’s good-hearted heroics. For those who take this stuff way too seriously, those who see in Star Wars a modern return to an old way of telling stories, though, I think Luke’s final moments in The Last Jedi make a perfect sort of sense. It puts him among a pantheon that includes the greatest heroes of song and story.

“Oh, father, don’t kneel down like that, because it breaks my heart. Please get up, Sir Ector, and don’t make everything so horrible. Oh, dear, oh, dear, I wish I had never seen that filthy sword at all.” And the Wart burst into tears. —The Once and Future King, by T.H. White

Luke: “Listen, I can’t involved! I’ve got work to do. It’s not that I like the Empire—I hate it—but there’s nothing I can do about it right now. It’s such a long way from here.”

It’s no minor detail that in the moments before he ascends to the next world, Luke sees the twin suns of his home world Tattoine. The quiet moment in the very first Star Wars film when a Luke barely out of boyhood gazes at the suns is the first real signal of exactly what kind of story we’re seeing. George Lucas wisely opened that movie on thrilling action that set the stakes, but it’s here in the drab and ho-hum Known World that we first pick up the thread of Luke’s life.

If Campbell deserves scholarly credit for that, Lucas deserves at least a fraction of credit for making Campbell’s work common pop culture knowledge. Pretty much any humanities teacher who needs to do a unit on the Hero’s Journey/monomyth can engage pretty much any class of North American high schoolers by holding Luke up as an example.

Our naïve farm boy begins in the Known World, a mundane place where all the regular rules apply—Tattoine, where a kid needs to drive all the way to Tosche Station just to have any fun. He receives a call to adventure from a distant princess, but when a wise old mentor entreats him to go forth on his adventure, he rejects the call. Soon, though, evil strikes his home and forces him on the path into the Unknown World. After crossing into this realm by way of a particular hive of scum and villainy, he ends up in the belly of a large malevolent entity, fights his way out of it, and destroys it.

It’s all familiar, but if you must have a “belly of the whale,” why not make it a planet-busting space station and then hinge the entire plot on destroying the thing? It’s at least novel. If the seams show a bit, it’s only because we’ve become so educated about those seams that we can’t help but look for them everywhere.

An Underworld in the Clouds

Campbell’s prescribed journey takes its hero through a long “road of trials,” knocking him down and giving him excuses to drag himself back onto his feet, over and over again, learning some lessons along the way. In many of these cycles, the nadir comes in a journey through an underworld—some terrible chthonic place of woe where the hero often sees apparitions, or is confronted by the specter of what may happen if he loses.

In The Empire Strikes Back, Luke’s journey along the road of trials and into the darkness of the underworld made Star Wars what it will always be remembered as, with its deeper philosophizing about the Force and the nature of evil. I was too young to really comprehend what was going on when I first saw the descent into the cave, not mature enough to see that Luke’s insistence on bringing his weapons against the advice of Yoda was a bad thing instead of a prudent thing.

Blowing up Alderaan near the beginning of Episode IV was George Lucas’ way of telling us all we needed to know about the Empire. Luke’s fight against a phantom Darth Vader that is revealed to share his own face told us something much more dire—that the Empire and the Rebellion were pawns on a galactic chessboard whose size we were just beginning to understand. Up until then, Luke’s journey was about little more than ruining the Empire’s day. After that scene, it became about defeating the evil in his own heart, to be followed swiftly by the revelation that this evil had already claimed his father’s.

Heroes Never Die

“Fate swept us away, sent my whole brave high-born clan to their final doom. Now I must follow them.” That was the warrior’s last word. —Beowulf, Heaney translation

Luke: “See you around, kid.”

For me, Luke has always had shades of King Arthur closer to his surface than any he might share with Odysseus (the hubristic wanderer) or Rama (the outcast monarch) from Hindu tradition. He’s a boy whose noble lineage is hidden from him for his own protection. Luke is, or wishes to be, a knight, from an order we’re told championed peace and justice. He gets a neat sword from a wise old mentor who spirited him to safety as a newborn, and he becomes a righteous warrior. Unlike Arthur, Luke is a rebel. Where Arthur has always been England’s avatar of conquest and order, Luke is trying to break a toxic status quo and restore a better world. That seemed more modern to me, but it also seemed more interesting.

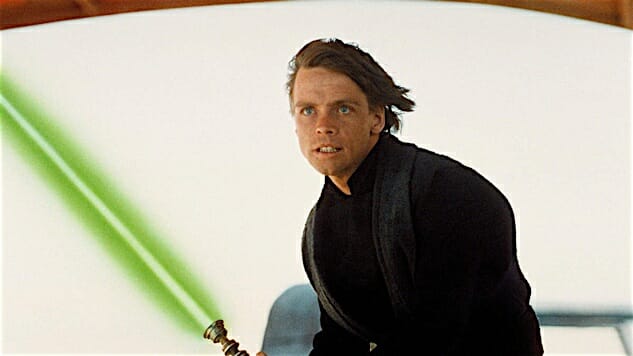

Luke has had a bad rap in the fandom from a lot of quarters in the character’s 40-year life. He’s been called whiny and virginal, dorky and callow. People point out that Han Solo has more charm and Leia has more grit. These people aren’t wrong, necessarily, but I feel they miss the point. Of the three main characters, Luke grows the most. When he strides into Jabba the Hutt’s palace in Return of the Jedi, the first we’ve seen of him since he got his shit kicked in by his homicidal megalomaniacal father, there’s something different about him—a confidence and determination that aren’t the same as his boldness from before. When he gives himself up to be taken to the Emperor, it’s not at all about a yearning for adventure or a thirst for excitement and glory. It’s a devotion to an ideal that’s as matter-of-fact as the samurai that inspired Lucas to create the Jedi.

That’s an arc. And as it turns out, not the end of one.

I was born in 1983, so I do not exaggerate when I say that I’ve known literally my entire life that Luke undergoes Campbell’s prescribed transformation and triumphant return. The monomyth he outlines includes things like gifts from a goddess or a magic elixir to be brought back to the people, and a magic flight back to the Known World. These elements are largely implied to occur after the end credits of Return of the Jedi, with his “elixir” being his position as a conquering Jedi Knight ready to revive the Jedi Order and bring back the peace and justice and stability that the Empire denied everybody.

But here’s what else happens, in a lot of these stories. These heroes, many of them, unleash their great strength or cleverness in their drive to right wrongs and fix the world. For a brief and shining moment, it looks like they succeed. Camelot thrives around the righteous men of the Round Table, with pure Sir Galahad in the Siege Perilous. Beowulf saves Heorot and returns to Geatland as a hero, loaded down with treasure, and in time succeeds mighty Hygelac to rule justly for 50 years.

And then, over time, these heroes bite off more than they can chew. The nature of the world changes, or maybe just reveals itself to be what it was all along. They grow older. Arthur’s Camelot may be a beacon, but the man himself is unequal to it, undone by sin and scandal. Beowulf’s rule is just, but his countrymen fail him, whether they be a thief who disturbs the sleeping dragon or the men who aren’t brave or strong enough to help him slay it.

And Luke tries to be a better mentor to a new generation of Jedi Knights, only to become so afraid of his nephew’s power that he momentarily considers the unthinkable, and pays for it. When you slay monsters and topple empires, you’re beyond the realm of neat, happy little endings where everyone loves you and nothing ever goes wrong.

But it isn’t all bad, either. Arthur’s court is diminished in its quest for the Holy Grail and then undone in civil war with his own bastard son, but we’re told he has sailed to the undying lands of Avalon. We want so badly to believe, as they assure us, that he will return.

The haters are partly right on this one: Luke’s last stand against Kylo Ren and the First Order is not what the Luke of Return of the Jedi would do. That Luke probably would waltz in with his laser sword and try to go to town on them, and he’d look good while doing it. But this Luke is the one who only now is wise enough to realize he isn’t and shouldn’t be the last of the Jedi—and that the Jedi weren’t all we thought they were. He defeats his foes and ensures his allies don’t die.

Then he goes on to another place, but I don’t think it’s all bad. The people are singing of him. Episode IX will be upon us soon enough. Force ghosts are a thing, guys. Maybe I should spell it out:

And many men say that there is written upon his tomb this verse: HIC IACET ARTHURUS, REX QUONDAM REXQUE FUTURUS (Here lies Arthur, the once and future king.)

I see why it was hard for some people to see Luke Skywalker at dusk. But do you see why I believe he will return?

Kenneth Lowe has been blown to Bermuda. He works in media relations for state government in Illinois and his writing has also appeared in Colombia Reports, Illinois Issues magazine and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Read more of his writing at his blog or follow him on Twitter.