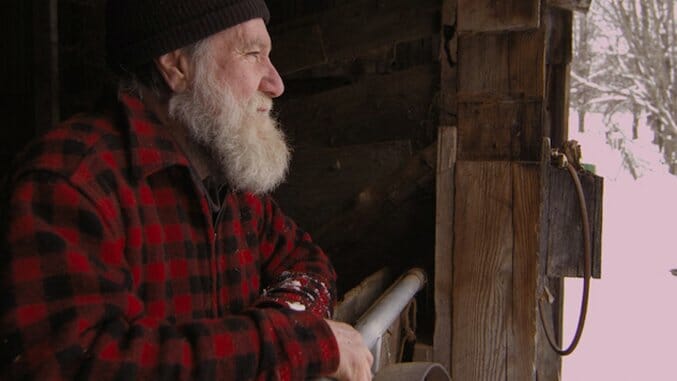

Peter and the Farm

If the success of a character study can be measured purely by the extent to which the character him-/herself draws one’s attention, then the new documentary Peter and the Farm is surely one of the most successful of recent years. On the surface, beyond his long white beard, there isn’t anything extraordinarily distinctive about Peter Dunning, a solitary farmer who has devoted 35 years of his life to tending his farm in Vermont, and whose lonely existence masks deep psychological scars underneath. Even his traumas are fairly mundane: estrangement from his ex-wives and kids, curdled hippie idealism, a hand accident that ended his artistic dreams. And yet, once you hear Peter speak in his dramatically galvanizing voice, one can’t help but sit up and pay attention to whatever cantankerous, world-weary, brutally candid statements he utters.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-