When I was at drama school, I went to a professor’s office hours for talk about my future. His name was Dan. He asked me what I wanted to do with all of this, which was big question at 20 (and still is). I told him I wanted to do something with performing and writing, but I didn’t know what yet (I still don’t). By way of encouragement, he gave me some examples of people who had managed to do just that. “Tracey Letts,” Dan said, before bending his head down as if to look over a pair glasses and say ‘or, obviously,’ “Sam Shepard.”

I’ve thought about this interaction a lot since Shepard passed away last week, because Dan clearly felt, in that little head bend, that there was something perfunctory about naming Shepard as a writer-performer. And he’s right: If anyone was to name the ten greatest dramatic writers of the 20th century, Shephard would undoubtedly be on that list, and chances are that he would be the only writer-performer to make the cut.

Shepard was the consummate writer-performer, in fact. To his acting he brought a writerly eye for idiosyncrasy and detail, and to his writing he brought an actor’s empathy and rhythm. These were the qualities that placed him at the nexus of contemporary American theatre, as he moved from working as an experimental absurdist downtown to the savage realist of Buried Child and Curse of the Starving Class, allowing him to reinvent American realism in an age of confusion and malaise. There was never another writer of his or any generation who could make the kitchen sink so believably violent, crackling and alive. And no one else infused that realism with a current of pitch-back surrealism quite like him.

We may be at a point, in the wake of his passing, where much of what he gave us has become ubiquitous enough that we often take it for granted. This is our mistake. Before disillusionment with the myth of American exceptionalism was in vogue, Shepard was there, disillusioned. Shepard broke up the family before it broke itself up.

These theatrical sensibilities were only amplified in his film work—both in his acting roles and in the filmic adaptation: the Farmer in Days of Heaven, Spud in Steel Magnolias, Frank James in The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford and of course pilot Chuck Yeager in The Right Stuff, for which he was rightfully nominated for an Academy Award.

In any one of those characters you’ll find a performance enhanced by the legend of the man and the depth of his insight. In many ways he was the only choice to momentarily play a poet-patriarch in the film adaptation of Tracy Lett’s play August: Osage County. The film cast a hatful of celebrities, but Shepard was uniquely qualified to capture the play’s sense of reflection and exhaustion.

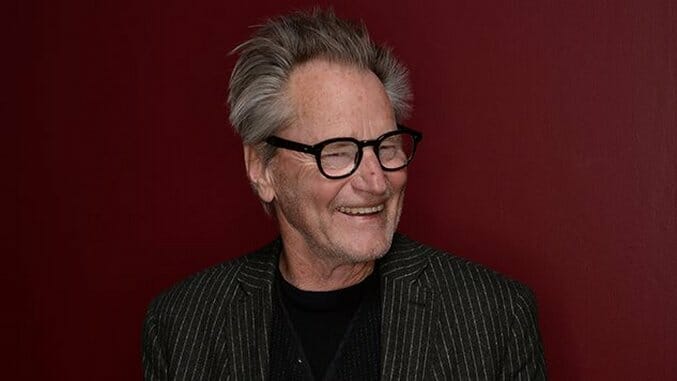

That’s our image of Shepard, and it contributes to his own mythology, in a way with which he may or may not have been comfortable. In the few days after his death, it’s been remarkable to see the number of people who identify Shepard as the rugged individualist. Face carved from limestone. I myself am guilty of this, and it’s not without basis in Shepard’s own life. He was, after all, one of the writers at the first O’Neill Playwrights Conference, and the first writer to walk out of it. He would leave a show in New York to fly to London without telling anyone. He was a resident of the Chelsea Hotel. He had an affair with Patti Smith. He drank, frequently, though, he wasn’t sure if it really benefited his writing as we like to imagine. He was handsome. He was quiet. Even the Paris Review once noted that “…Shepard is easy to imagine as one of the characters in his own work. In person, he is closer to the laconic and inarticulate men of his plays than to his movie roles.” When people talk about some imaginary lost ideal of American manhood, they may in fact be thinking of Shepard.

But now that he’s gone, I can’t help but feel that this is too uncomplicated a view of the man. Something is missing. As to what that something is? When I first read Shepard and devoured his movies, part of me felt he was unknowable. In reality it was a case of not being able to see an object that was so close to my face. There of course would seem something unknowable of anyone who poured so much of himself into his work. Shepard’s psychological nuance remains unparalleled. There is something of the soul of the 20th century in him. And the 21st, and, I expect, the 22nd.

For proof,here he is on the psychological scars of the America he grew up in:

Those Midwestern women from the forties suffered an incredible psychological assault, mainly by men who were disappointed in a way that they didn’t understand. While growing up I saw that assault over and over again, and not only in my own family. These were men who came back from the war, had to settle down, raise a family and send the kids to school—and they just couldn’t handle it. There was something outrageous about it.

As the face of American playwriting continues to change, even if it changes beyond what we could possibly expect, there is something universal in the work of Sam Shepard. A universality born of his own synthesis as a master of multiple art forms—-an understanding we were fortunate enough to have him put into words. That he will always be the quintessential American dramatist is a given (his childhood nickname was, after all, Steve Rogers). He remains, additionally, one of the few great American artists with a firm grip on just how fortunate he was.

A friend reminded me of a quote from True West, my favorite work of his, and one that—as a stage play about brothers arguing over a screenplay—lands neatly in the intersection of the worlds Shepard inhabited.

“When you consider all the writers who never even had a machine. Who would have given an eyeball for a good typewriter. Any typewriter. All the ones who wrote on a matchbook covers. Paper bags. Toilet paper. Who had their writing destroyed by their jailers. Who persisted beyond all odds.”

How lucky we are that Sam Shepard had a machine.