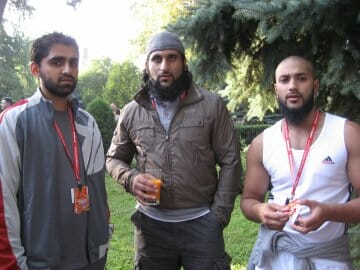

Above, from left to right: Asif Iqbal, Shafiq Rasul and Ruhel Ahmed. Photo credit: Lala Ráscic

There were accolades aplenty for female filmmaker Andra Štaka at this year’s Sarajevo Film Festival (Aug. 18-26), culminating with her receiving top honors and the Heart of Sarajevo prize for her debut film Das Fräulein. A complex portrait of former Yugoslav women living in Zurich because of the disintegration of their country into war, Štaka’s film stirred critics and public alike at the 12th annual festival, placing third in the audience participation poll. Das Fräulein also produced the best actress prize, with the award going to Marija Skaricic for her maverick emotional style.

As might be expected at a film festival focusing on the Balkan region, the violent breakup of Yugoslavia and the transitional friction of communism into capitalism following the fall of the Berlin Wall were twin themes reverberating throughout the 200-odd films from the region’s 12 participating countries. Good Luck Nedim, by Slovenian filmmaker Marko Šantic, claimed the prize for best short film. Clocking in at just 13 minutes, Good Luck Nedim is a poignant portrayal of a terminal cancer patient lacking proper official papers trying to cross Slovenia from Germany in order to die in his Bosnian homeland. Croatian director Ivona Juka won best documentary prize for her Facing the Day, an existential glimpse at three inmates rehearsing for a prison production of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, examining the impact of recent history on their lives. Best actor award went to Rakan Rushaidat for his role in Antonio Nuic’s All For Free, in which Rushaidat sells his possessions and seeks to do something memorable after all his friends are killed in a Bosnian bar fight.

Non-competition entries from outside the region were heavily represented by films exposing the effects and side effects of America’s five-year old War on Terror. The Road to Guantanamo, directed by UK filmmakers Michael Winterbottom and Matthew Whitecross, is a controversial fusion of feature and documentary that peers into the darkness of the Guantanamo Prison through the eyes of three young British men held there: Shafiq Rasul, Ruhel Ahmed and Asif Iqbal. Post-war Iraq, meanwhile, is the subject of two American documentaries: Iraq in Fragments, by James Longley, and My Country, My Country, by Laura Poitras. Filmed stealthily during the run up to elections in Iraq, My Country, My Country provides living room access into Sunni family life under U.S. occupation that surprises when moments of humor and sweetness break through the weeks of frustration and uncertainty.

This emphasis on films with political overtones is a choice rather than coincidence, according to festival director Mirsad Purivatra. Speaking with Paste before opening night, Purivatra stressed that he sees the festival not only as a platform for regional film development, but also for world political concerns. Undoubtedly, a hefty majority of the festival’s audience share Purivatra’s sensibility. The Road to Guantanamo sold out the massive open-air theater and won the audience participation poll, while its three young British protagonists were treated like celebrities at the invitation-only opening-night party.

Shy, and certainly conspicuous among the glamorous mingling of Balkan actors, models and pop stars, the former prisoners spoke candidly with Paste about their terrifying two years of threats and torture while being held in Guantanamo without ever being charged with a crime. “If you would have told me two years ago that I would be here now,” the salient-bearded Rasul began, nodding to the surrounding rose garden of gaiety. White-gloved waiters were shuffling silver trays of champagne and hors d’oeuvres. Black-skirted models were passing out Jack Daniels with You know you want it smiles. A string quartet was bowing highlights from the Western cannon. He shook his head and left his sentence unfinished at his dramatic swing of fate from imprisoned terrorist to opening night celebrity. Irony aside, Rasul said he hoped the film would help make people aware “that to torture is illegal. It’s not OK for anyone, not even the U.S., to torture people.” When asked if he was bitter, he paused, his penetrating eyes unblinking, and responded, “I lost two years of my life, but bitterness is not going to control my life.”

Politics was not the only course on the festival’s menu, as the 11-day event was peppered with eclectic fare such as Philippe Parreno and Douglas Gordon’s Zidane, a 21st Century Portrait, an intriguing close up of French soccer star Zinédine Zidane over the course of a match. Tribute programs to the cine-sleaze of Bronx-born Abel Ferrara and the grim, long-take realizations of Hungary’s Bela Tarr also featured among the cinematic sidebars.

For me, the festival’s opening bang proved the biggest. With bats flitting about the Sarajevo sky and Nick Nolte and U2’s Bono among the stars on hand, Corneliu Porumboiu’s 12:08 East of Bucharest charmed those fortunate enough to secure open-air seating to the festival’s most sought-after ticket. A hilarious take on collective introspection, 12:08 East of Bucharest is about a small town in Romania that looks back at the 16 years since the overthrow of Dictator Nicolae Ceausescu and asks whether or not a revolution occurred (the literal translation of the Romanian title is “Did it or did it not happen?”). Deftly handling this heavy theme via a live television show that has telephone callers disputing the legacy of the small town revolutionaries, Porumboiu melds wonderful acting, tight scripting and clever camerawork into Something Special. Dark but not morbid, witty without becoming frivolous, this film is worth putting into your celluloid search engine – one that tickles the head and touches the heart.

That combination, along with Porumboiu’s deft touch and fine balance, was often lacking in other films previewing in Sarajevo. Given that their subject is the suffering from the fallout of war (whether it be Terror, Yugoslavian or Cold), the filmmakers had no trouble provoking audience sympathy in their features and documentaries. Often, however, the reach of their mission exceeds their grasp of the craft, and the viewer experiences more idealism than realization.

Continuing a troubling trend that began in 2004 with the Cannes Film Festival’s beatification of Michael Moore for his fizzling Fahrenheit 911, a significant amount of the enthusiastic jury and audience response in Sarajevo seemed based more on political needling or emotional tugging than cinematic brilliance. One example of this is the Bosnian film Carnival by director Alen Drljevic. Despite a standing ovation and a second-place finish in the audience participation poll, weak transitions and unimaginative editing of its heartrending interviews plague this investigation into the disappearance and deaths of Bosnian men during the war.

And yet I would not hesitate to admit that Drljevic’s heart, like Sarajevo’s (prominently displayed through the festival as its logo) is in the right place, as Hollywood or even Sundance can never be. Drljevic’s quest to confront history and resolve the past, while clumsier than Porumboiu’s 12:08 East of Bucharest, is a worthy one for our cynical and shame-filled age. Which just might explain why I found myself instinctively participating in Carnival’s thunderous closing applause.