Silence is in thrall to the spiritual crises of its two authors, novelist Shusaku Endo and filmmaker Martin Scorsese, and of its protagonist, Sebastião Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield), a Portuguese Jesuit living in the 1600s who must either reckon with his beliefs or die for them. Despite being separated from one another by both geography and time, Endo and Scorsese feel like creative kindred spirits: Endo, a member of Japan’s third wave of postwar writers and essayists in the 1950s, explored Christian identity, and thus his identity as a Roman Catholic, through his work, much as Scorsese has grappled with his Roman Catholic background—from Mean Streets, whose protagonist is torn between his Mafioso dreams and his Catholic upbringing, to The Last Temptation of Christ—for his whole career.

So Silence, Scorsese’s big screen adaptation of Endo’s best-known text, is a well-tuned thematic union between two artists whose art dissects matters of ideology, of what it means to believe, of the cost our beliefs incur upon ourselves and our fellow believers. It’s also a taxing and unforgiving film that relentlessly interrogates Christian dogma by reshaping the Endo book into cinema, which itself reshaped real world history into literature. Both film and novel tell of how, in 1600s Japan, Japanese Christians were brutally suppressed by their government for their choice in worship, and how doomed Jesuits attempted to guide the Kakure Kirishitan (“hidden Christians”) in their time of need. Both tell of the folly of spreading the words of Christ in unfamiliar lands—lands where those words are unwelcome.

It’s rare for a movie to demand its viewers do their homework before buying a ticket, but context for Silence is a boon (though not a necessity) for comprehending the “why” of its plot’s grim particulars. The film’s source material may be historical fiction, but it’s impossible to ignore the emphasis Endo put on “historical,” perhaps because he took Silence’s history personally. Scorsese provides background for the film’s chronicle of religious persecution in its first scene, where Father Cristóvão Ferreira (Liam Neeson) stares wide-eyed as members of his Japanese flock are bound and tortured on the edge of a hot spring. Later, Scorsese references the Shimabara Rebellion, a peasant uprising that lasted five months and was soundly crushed by the joint armies of daimyos representing several Japanese domains.

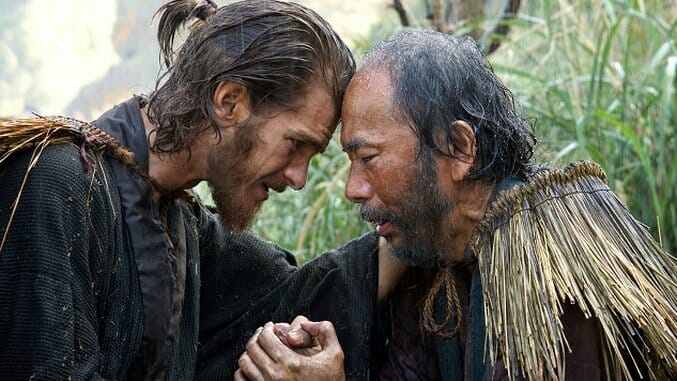

But Silence is chiefly concerned with Garfield’s character before Neeson’s: Rodrigues, formerly a student of Ferreira’s, is determined to seek out his erstwhile teacher and verify reports of his apostasy. Upon arriving in Japan alongside fellow padre Francisco Garrpe (Adam Driver), Rodrigues grows increasingly confounded by the country, its people and his god’s refusal to answer his prayers.

Silence derives its title from the last of these three bewilderments, referring to the slow, agonizing rate at which Rodrigues’s faith unravels while God remains deaf to his pleas. The Japanese government subjects its Christians to forms of punishment as cunning as they are cruel, and Rodrigues can only stand by and bear witness to their pain. Watching them suffer is how he suffers. Unlike, say, Mel Gibson, whose The Passion of the Christ gorily depicts the end of Jesus’s life in a vulgar blend of revulsion and awe, Scorsese treats the desecration of human bodies with dignity, preferring not to linger longer than he must on images of physical anguish. That, of course, is in part because he doesn’t need to: Silence’s aural component, punctuated by the wailing of the oppressed, is reminder enough of its violence when violence alone would normally suffice.

Yet this is a film about perspective, specifically Rodrigues’s perspective, and how observing such barbarity forces him to reconsider the lens through which he sees the world. Which is to say that his lens ends up shattering. Seeing the people he’s supposed to shepherd put to death, whether by drowning, or burning, or worse, upends his belief structure and awakens him from the dreams he’s embraced his entire life—the dream of Christ’s love, the dream of glorious martyrdom, the dream of eternity in paradise. Silence asks us to lend Rodrigues our empathy, which anyone in his position surely deserves. He’s like a newborn lamb taking his first steps upon ground he’s never tread before, a man just made aware that the laws he has used as his moral compass were always just assumptions.

Silence pivots on this development, which begins in earnest as soon as Rodrigues and Garrpe come ashore but escalates in the movie’s second half, when they’re split and captured by Japanese officials (represented by the great Tadanobu Asano and the greater Issey Ogata) intent on sniffing out Kakure Kirishitan in small coastal villages. The goal is to compel them to apostatize by trodding on engraved images of Christ, but with Rodrigues in their grasp, the scope of that goal expands: They instead focus on persuading him to apostatize, while also exposing him to his own ignorance. Silence invests in the plight of Rodrigues—because how could it not?—but Scorsese doesn’t necessarily consider him innocent, and neither do his hosts, and therein lies the film’s complex heart.

The best intended virtues of the lead characters collide with guilt passed down to them by their forebears. Neither Scorsese nor his characters directly invoke the spectre of European colonialism, but it’s there, woven into the film’s subtext, and Rodrigues is its agent, regardless of whether he or the movie acknowledge it. He is the outsider wandering into a culture he doesn’t understand, oblivious of his presumptuousness at preaching gospel to people whose language he hasn’t bothered to learn. Silence isn’t just a portrait of horrific abuses committed in keeping with humanity’s tradition of butchering the hapless unfortunates who believe differently than the ruling class. It’s a critique of fundamentalist Christian pretensions. It’s a Möbius strip of spiritual doubt.

On the opposite side of the lens, manned by cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto, Scorsese can be heard wrestling with his personal metaphysical crises, just as Endo, who was baptized only six decades and some change after the Japanese government officially repealed the edicts banning Christianity in Japan, must surely have wrestled with his own while writing his novel. Silence is a movie composed of questions: What’s the truest test of a person’s faith? How can faith adapt to suit the faithful, and can it be adapted at all? Is the realization that it perhaps cannot be adapted the most painful realization a person can arrive at? Most importantly, is it possible to have faith without struggle, and if so, what does that mean in regards to the role of Christ and the role of Judas? The movie isn’t heavy handed, but the relationship between Rodrigues and Kichijiro (Y?suke Kubozuka), his PTSD-stricken convoy in his journey to find Ferreira, clearly mirrors that of the Son of God and his treacherous disciple.

It should go without saying that the package Scorsese has carefully, delicately crafted for storing these questions and concepts is stunning. Though in his mid-70s, Scorsese nonetheless possesses the fire and vitality of a much younger filmmaker, which he supplements in Silence with incredible grace. It’s a harsh experience made with a gentle hand and shot through the eyes of a master director. Scorsese has been trying to get his version of Silence (which marks the second time Endo’s book has been adapted into a movie, the first being Masahiro Shinoda’s 1971 film) made since 1990, just after the release of The Last Temptation of Christ, and you can sense his patience along with his passion in each of his movie’s frames. More importantly, that patience has paid off: This isn’t just one of the best films of 2016, it’s one of the most richly layered, faith-driven narratives you’re likely to encounter in modern cinema.

Director: Martin Scorsese

Writers: Jay Cocks, Martin Scorsese; Shusaku Endo (novel)

Starring: Andrew Garfield, Adam Driver, Issey Ogata, Tadanobu Asano, Liam Neeson, Y?suke Kubozuka

Release Date: December 23, 2016

Boston-based critic Andy Crump has been writing about film online since 2009, and has been contributing to Paste Magazine since 2013. He writes additional words for Movie Mezzanine, The Playlist, and Birth. Movies. Death., and is a member of the Online Film Critics Society and the Boston Online Film Critics Association. You can follow him on Twitter and find his collected writing at his personal blog. He is composed of roughly 65% craft beer.