By the time Daniel Craig started his turn as Agent 007, every central tenet of the Bond mythos had been challenged somehow. James doesn’t have the Soviet Union to kick around anymore—his enemies in every film since 1995’s GoldenEye have been terrorists or sophisticated criminals. That same film featured Judi Dench’s most memorable line in her entire seven-film run as spymaster M, in which she opines that Bond is a “sexist, misogynist dinosaur, a relic of the Cold War …” (Pierce Brosnan’s 007 would go on to bed an average of two women per film across four films, according to the bean-counters.)

Daniel Craig is one Bond removed from this withering lampshade line, and it’s hard not to think he’s laboring under writers who feel a little uncomfortable with a more virile Bond. As the pre-Spectre chart in the link above notes, Craig’s 007 has had the fewest dalliances of any Bond, and as this depressing one notes, he has drunk the most.

Adjusting for Spectre (two ladies) and even adding Moneypenny to his conquests (Skyfall plays coy), he has whipped out his License To Kill before an average of 1.75 women per film. By comparison, his forebears average at least two ladies per film.

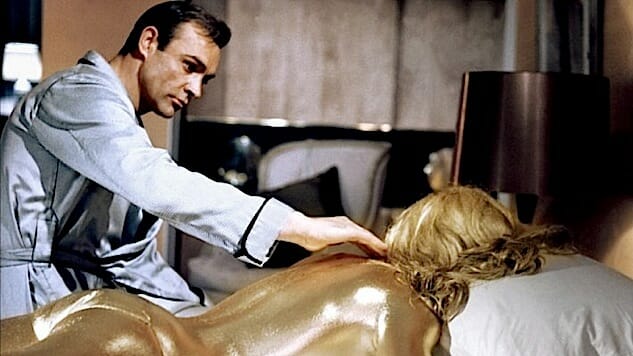

Canonically, this is the same agent who in past portrayals has cheerily leered at gypsy belly dancers (From Russia With Love), frequently begun the movie in female company (Tomorrow Never Dies as just one example) and declined to call in for debriefing in favor of a touchdown dance with a ladyfriend (too many to list).

We can’t even have fun with his female acquaintances’ names any longer. Past companions have included Pussy Galore, Kissy Suzuki, and for goodness sake, Plenty O’Toole. Yet only the sharp-eyed credits viewer will notice that Quantum of Solace’s disposable woman’s name was Strawberry Fields (not evocative of genitalia unless you’re really stretching). And that’s as clever as any of them get.

Wherefore did this suave superspy become a dour trainwreck? I asked Will Scheibel, a professor at Syracuse University who wrote about the film adaptation of Casino Royale in “Revisioning 007: James Bond and Casino Royale.”

Vesper Lynd: You think of women as disposable pleasures, rather than meaningful pursuits. So as charming as you are, Mr. Bond, I will be keeping my eye on our government’s money—and off your perfectly formed ass.

James Bond: You noticed.

—Casino Royale, 2006

Scheibel said shifting societal mores toward how men treat women might be exerting some influence over the newest portrayal of Bond, but so is the shrewdness of his franchise’s masters.

“[The Craig movies are] an attempt to capture the darker, more psychologically realist tone of the Ian Fleming novels, which are quite brutal,” Scheibel says. “They’re not playful or tongue-in-cheek the way that the Bond films are.”

Part of that might be push-back against Pierce Brosnan’s portrayal, which Scheibel said lapsed into self-parody after its strong first outing in GoldenEye.

“A lot of Bond fans felt that the character had become a joke. I think part of [the Craig films] was an attempt to go back to the drawing board and get closer to the original conception: Darker, less likable, more realistic and with more at stake. Bond can actually get hurt and die.”

So, manifestly, can his lovers. The films since Casino Royale have been particularly deadly for the women who have handled Bond’s Walther: Add it up and you see four of the seven lucky ladies in Daniel Craig’s films have met decidedly unlucky ends (again, if you count Moneypenny and don’t count the fact she loses her field agent superpowers at the end). That is a better than even chance of dying. (By comparison, the most recent link above says the franchise average survival rate of a Bond girl is about 1 in 3.)

No wonder Daniel Craig’s Bond drinks so much.

The films also seem more interested in interrogating the audience’s expectations of Bond’s casual use of women, Scheibel says.

“We’re invited by Vesper [in Casino Royale] and other characters to question his ethics and moral compass. It’s a process of laying Bond bare. You get films that are nostalgic, but are asking you to examine your nostalgia.”

Critical of Bond’s dalliances or not, there seems to be a coldness, even a meanness, to his relationships in the Craig films. The fact the first two Craig films revolved around Bond’s heartbreak over one woman (even one as mesmerizing as Eva Green’s Vesper Lynd) make his treatment of women in the latter two films seem callous: Skyfall’s Sévérine (Bérénice Marlohe) and Spectre’s Lucia Sciarra (a much-ballyhooed and little-used Monica Bellucci) both bite it graphically and within minutes of knowing 007’s cold embrace.

James Bond is what every man would like to be, and what every woman would like between her sheets.

—Raymond Mortimer’s review of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, 1969

So what happened to the virile, strutting Bond of earlier films?

Scheibel said the literary version of Bond, especially in the earlier Fleming novels, might not be as recognizable to younger, film-version-only fans who delight in his free attitude toward fraternization while on government time. (Scheibel disclosed that GoldenEye was the first Bond film he was old enough to see in theaters—better known as the film in which Russian antagonist and Bond playmate Xenia Onatopp finds death orgasmic.)

“When I read the Fleming novels, I’m shocked by a lot of the sexist language that’s used to describe his dealings with women,” Scheibel says. “In that sense, the Daniel Craig films are very different, but tonally and stylistically I think they’re going back to that Fleming model.”

It’s not the first time the character has been rebooted and his sexual overtones re-examined, either. Timothy Dalton’s Bond was thought of as monogamous, recalls Dann Gire, Chicago area film critic and President of the Chicago Film Critic Association, yet that was hardly the case. Dalton’s inaugural Bond film, 1987’s The Living Daylights, paired him with a comely Soviet defector for much of the film, and some in the media read too much into it.

“I remember vividly how the media went nuts over James Bond’s new turn toward monogamy in The Living Daylights,” Gire says. “It was at the height of AIDS awareness and Hollywood hacks were abuzz with how the 007 movies responsibly responded by having Timothy Dalton’s agent stick with one woman for the whole adventure. Except they were dead wrong, victims of wishful thinking or creating a story where there was none.”

As Gire points out, the movie’s cold open has Dalton parachuting onto a young woman’s boat, borrowing her phone to check in with MI6, and then thanking her thoroughly.

Raoul Silva: Well, first time for everything, yes?

James Bond: What makes you think this is my first time?

—Skyfall, 2012

Yet, in a world of deafening speculation about Idris Elba possibly taking up the role of Bond, one or two interviews wherein Daniel Craig seemed less than enthused about continuing in the role, and a riotous list of totally implausible reboot ideas by the A.V. Club, it’’s fair to wonder whether Bond’s status as a cisgender male stud might soon be upended somehow.

In a memorable 1998 interview with Barbara Walters, gay British actor Rupert Everett revealed he was adamant about shopping around a script for a gay Bond. When asked who his “Bond girl” would be, Everett said: “Dennis Rodman.”

He added: “I’m serious.”

Back in 2012, you’d think that this idea had never before been uttered aloud, what with the raised eyebrows over the suggestive scene between Javier Bardem’s gay antagonist Silva and a physically bound, captive Bond.

(Though Craig’s description of Silva’s sexuality is a bit more pansexual: “I’m like, I think he’ll fuck anything.”)

The scene is interesting for more than just its tame bit of titillation. Bond’s villains have also changed, and the fact Silva might not be straight might actually be a step forward for the franchise in some ways. Bond’s villains of late have become more and more like him, after all: GoldenEye’s 006 and Skyfall’s Silva are both bitter MI6 rejects, The World Is Not Enough’s Malik an unfeeling physical powerhouse, Die Another Day’s Gustav Graves a sneering aristocrat who openly monologues that his persona is based on Bond’s.

“For a long time, James Bond’s villains were painted to be everything that James Bond was not,” Scheibel says. “You had these characters that are marked by an ethnic or sexual otherness. Everything Bond does not possess. Since GoldenEye, the villains are more often like Bond’s dark other. You dial James Bond ever so slightly in another direction, you get Sean Bean from GoldenEye, or Javier Bardem from Skyfall.”

If Skyfall meant to suggest that Bond can loosen up a bit about his defined gender role, it also proved the franchise is unwilling to leave behind its formula: The film begins with a gun-toting Moneypenny and a nail-eating female M and ends with M safely male and Moneypenny back behind a desk.

“I think that one of the things I hear a lot of young people ask, and I’m always glad they are: Why does James Bond have to be an ostensibly straight, male, British character?” Scheibel says. “Can we have a female James Bond, a black James Bond?”

Can we? Would that shake James out of his funk? It would be a liberating moment for a good number of his fans and for the character, who seems trapped in a cycle of dour reboots, forced to wring his hands over lost women instead of enjoy their company—to do battle with his mirror image instead of fighting colorful henchmen with ridiculous names. Who knows what romantic pairings might result when writers are given the freedom to step outside that formula?

Even though it would modernize the character, a sexual revolution like that would somehow feel right at home in the ’60s, too.