My First Time with My First Film

Zia Anger's live performance documentary is finally available for at-home consumption—within a certain context.

Images via MEMORY Movies Features Zia Anger

Note: The following contains potential spoilers for Zia Anger’s My First Film.

![]()

In some places it’s listed as a 2018 film, in some 2019, but only in 2020 has My First Film —Zia Anger’s second feature—become available for at-home consumption. For the occasional venue that’s hosted it, the film’s duration is usually labeled as 75 minutes; when my RSVP was confirmed on April 8th, the message advised me the film “can run anywhere between 85 and 110 minutes.” Our mid-afternoon session with an audience of about 60 lasted almost exactly 90. I haven’t stopped thinking about it since.

Time is essential to Anger’s ever-shifting opus, because context is everything. Performed live in theaters throughout 2018 and 2019—often at film festivals and colleges, with the final performance, as described in an interview in Filmmaker Magazine, unexpectedly ending up being at Borscht before the pandemic canceled a few future UK dates—My First Film is now available through “preview” streams online all while Anger and her studio/distributor, MEMORY, feel out ways to get people to see it. As they responded in an email: “…we are figuring that out right now.”

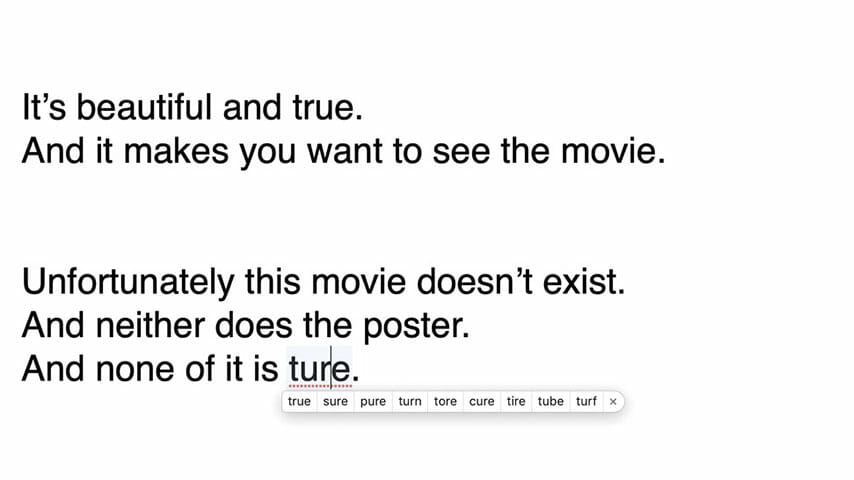

To put its conceit lightly, My First Film is never quite the same. It’s at the mercy of not just the audience (as are most moviegoing experiences), but of the mood of the performer (the director, alone with only her laptop), of the venue, of the efficiency of the technology used, of all previous performances, of access, of class, of our individual ability, our intimate desire, to justify using our time anymore. It is built to be singular, built as we watch it from screengrabs and YouTube videos and Google searches and whatever detritus Anger has culled from the unending, vista-defining flotsam of her, and our, digital selves. The frame is her laptop screen, the film narrated via her typing into Apple’s TextEdit, replete with real-time typos and rewrites, meaning mutating as she deletes and then re-words herself. She tells us what the movie is about, repeatedly, were we not already clued in by the title: It’s about the making of her first movie, a movie from a decade or so ago so unseen it’s practically listed nowhere. We watch big chunks of it with her; she has no hesitation in foregrounding the experience with the admission that the movie has been unseen for a reason. It’s a bad movie.

On April 8th, Bernie Sanders “suspended” his campaign, and Anger, who refrained from using her voice almost completely throughout her film, revealed, during that particular performance, her head with a Bernie Sanders hat fit snugly on top. She typed, before we “began” (though as soon as we logged in we’d arguably begun), that she wasn’t feeling good that day. Many of us, too, were processing the news of what it meant to be stuck with the illusion of choice in a world already so dramatically out of our control. Which is why she may have first called us “blasé,” at least until we began to take the short videos she texted to us (via iMessage) and pass them to other numbers that appeared on screen. The videos were unearthed corpses from her past Instagram stories, Anger explained, and the dumbly laborious process of getting those stories deserves more enthusiasm and participation from us select bystanders. We obliged; I accidentally sent someone a video I took of Jackie Chan in Island of Fire until I realized what was actually happening.

My First Film is a literal deconstruction: Anger takes us through her first finished film, bit by bit, condensing its two and a half hours into a series of key scenes, relaying anecdotal and apocryphal information about how the movie came about, how it was funded, how it and she came to be—came to be there, really, a filmmaker manifesting a film about a previous film right before our eyes. As she edits herself—typing, for example, the word “sick” and then quickly deleting to replace with the word “pregnant”—she draws attention to the artifice of what she’s doing as much as to the eccentricity of it. She follows a script, but that’s never absolute. She’ll say something happened a month ago, then erase and correct it to “five weeks.” We’re in this moment, this unique spot, together, she seems to be reassuring us, even if this moment is all kinds of contrived.

As she grows increasingly intimate with us, talking through her personal life and her cast of non-professional actors (all people from her hometown, including her father) and her responsibility as a director—all within the nebulously artsy confines of this unseen film she wrote based unabashedly on herself—we’re bound to interrogate ourselves in that moment, the responsibility we bear, as an audience, to the film we’re watching, the film we’ve agreed to some to extent to help create. Anger brings us to a party scene, a cadre of kids in their early 20s downing endless beer, and relates the consequences of getting the cast sloppy drunk in order to capture an underlying sense of naturalism. What is our responsibility as we bear witness? The “DONATE” button looms large at the bottom of our screens; we know she can’t keep doing this without money.

Anger has an incisive sense of humor about her failures, especially about her first film, which she concedes may not actually be her first film because nobody saw it. If a movie is never viewed, is it even a movie? We are made complicit: My First Film may actually be her first, technically, when it comes to modern models of distribution and how the industry refers to independent filmmakers, and in this time, an unprecedented iteration of our shared reality, we’re given the chance to assist in pulling apart, and rebuilding in our image, what it means to share in a communal cinematic experience. She does more than ask us to join in, to become part of the film at the beginning and at the end, she joins us in explicating this “thing” she does, undergirding raw, plainspoken revelations with grief and acceptance. During My First Film, we embrace what any of this means together. It feels like a rare, beautiful moment of levity to swallow back tears in unison.

One story, one of her final stories—true or not, as told by her dad—details her conception. It involves a little film canister and one of her two moms, who is a mime, and a plastic syringe used to feed kittens. It beams with mythic portent—the film-maker born from the same shell as the art she makes—reeks of the stuffing of good storytelling. During it, I thought of the fertility treatments my wife and I, but especially my wife, have gone through, of all the syringes placed against the cervix and the semen samples and the renewed hope, every month, that if we do everything as we’re supposed to, entelechy will shake out to be us, quarantine long behind us, pregnant. Our ideal selves, a family. I thought instead how, as we both turn 37, as we lose these precious months to our own evolutionarily incompetent reproductive systems, IVF might be our only chance. Were we able to afford it. We aren’t. Meanwhile, I have to justify my job just so I can keep it. We all do. All we may have left is to accept, and to grieve, and to move on. Or maybe that’s just my own shit.

One of the final sentences Anger typed to us on April 8th, 2020, wearing a Bernie hat, was “I’m thinking of you all.” There was a lot of warmth in that, and I felt the same way. I’m thinking of everyone who saw that movie with me, about everyone who saw it before me, about everyone who didn’t see Anger’s first film, and everyone who hasn’t seen My First Film. These days, I’m thinking a lot about myself. I’m thinking of you all.

![]()

The best way to watch My First Film right now is to follow Zia Anger on Twitter, set an alert, and as soon as she tweets about a showing that day, follow her directions and RSVP as quickly as possible. Then donate.

Dom Sinacola is Associate Movies Editor at Paste and a Portland-based writer. You can follow him on Twitter.