“When I first came out to L.A. [in 1968], my friend [photographer] Joel Bernstein found an old book in a flea market that said: Ask anyone in America where the craziest people live and they’ll tell you California. Ask anyone in California where the craziest people live and they’ll say Los Angeles. Ask anyone in Los Angeles where the craziest people live and they’ll tell you Hollywood. Ask anyone in Hollywood where the craziest people live and they’ll say Laurel Canyon. And ask anyone in Laurel Canyon where the craziest people live and they’ll say Lookout Mountain. So I bought a house on Lookout Mountain.” That’s a quote from the one and only Joni Mitchell, one of many beloved artists who were somehow influenced by the folk-pop scene in the Laurel Canyon neighborhood of Los Angeles in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Last year, Jakob Dylan produced a documentary about this Laurel Canyon scene, called Echo in the Canyon, which featured many of the most recognizable faces from the era, including Brian Wilson, Ringo Starr, Michelle Phillips, Eric Clapton, Stephen Stills, David Crosby, Graham Nash, Roger McGuinn and Jackson Browne, plus artists who’ve been carrying the legacy of the Laurel Canyon sound beyond the 20th century, including Tom Petty in his final filmed interview, Beck, Fiona Apple, Cat Power, Regina Spektor and Norah Jones. The influence of the sounds that were being made during the Laurel Canyon era can be felt across rock, pop and folk even today.

Last year, our critic noticed a trend in Laurel Canyon sounds appearing throughout indie music. Artists like Jenny Lewis, Weyes Blood and Molly Tuttle have been channelling Mitchell, Carole King, Emmylou Harris and more artists who were posting up with the likes of Neil Young, Jackson Browne, J.D. Souther, Glenn Frey, Don Henley and Gram Parsons in the late ’60s. The free spiritedness of the hippie era could be felt across the cottages and hills dotting the Laurel Canyon area. In honor of this “bohemian refuge” and the distinct sound it inspired (plus Neil Young and James Taylor, two stalwarts of the scene, have released albums this year), we decided to gather a list of albums we love here at Paste that came out of that era. While the Laurel Canyon sound can undoubtedly be heard today in artists like the aforementioned Weyes Blood plus Jonathan Wilson and Dawes, we decided to restrain this list to albums that arrived around the actual time that all these folks were living in Laurel Canyon. Not every album listed here was made in L.A. as a direct result of hanging out with Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young (the most notable residents of Laurel Canyon during this time) or one of the other Laurel Canyon legends, but they all share a similar sound, style and spirit undoubtedly inspired by the Canyon. Please enjoy the 10 best Laurel Canyon albums.

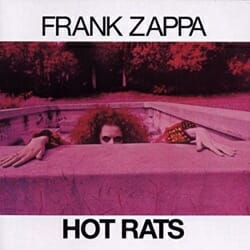

10. Frank Zappa: Hot Rats (1969)In 1968, you could have dismissed Frank Zappa as an unsavory-minded joke rocker with a hideous mustache. You would have been wrong, of course, but you could, conceivably, have believed such a thing. In 1969, Zappa, temporarily exiled from his Mothers of Invention, released an album with no jokes and very little rock-and-roll. Hot Rats, a kaleidoscopic exercise in jazz-rock fusion, introduced fans to Zappa’s virtuosic compositional abilities and near-limitless fascination with lengthy guitar solos. The rocker’s approach to jazz bursts with cartoonish energy, in part due to his unusual use of speed manipulation to rev up the rhythm tracks. Of particular interest are the opening numbers: “Peaches En Regalia,” an astonishing circus orgy of melodic ideas, and “Willie the Pimp,” a sleazeball anthem sung by gruff-voiced Zappa associate Captain Beefheart. Zappa would follow it up with two subsequent fusion records: Waka/Jawaka and The Grand Wazoo. —Zach Schonfeld

10. Frank Zappa: Hot Rats (1969)In 1968, you could have dismissed Frank Zappa as an unsavory-minded joke rocker with a hideous mustache. You would have been wrong, of course, but you could, conceivably, have believed such a thing. In 1969, Zappa, temporarily exiled from his Mothers of Invention, released an album with no jokes and very little rock-and-roll. Hot Rats, a kaleidoscopic exercise in jazz-rock fusion, introduced fans to Zappa’s virtuosic compositional abilities and near-limitless fascination with lengthy guitar solos. The rocker’s approach to jazz bursts with cartoonish energy, in part due to his unusual use of speed manipulation to rev up the rhythm tracks. Of particular interest are the opening numbers: “Peaches En Regalia,” an astonishing circus orgy of melodic ideas, and “Willie the Pimp,” a sleazeball anthem sung by gruff-voiced Zappa associate Captain Beefheart. Zappa would follow it up with two subsequent fusion records: Waka/Jawaka and The Grand Wazoo. —Zach Schonfeld

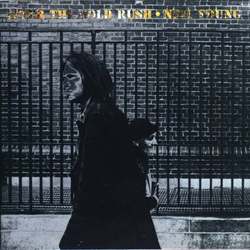

9. Neil Young: After the Gold Rush (1970)Along with Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks, After the Gold Rush is one of the greatest break-up records ever made regardless of intention. Even though it has nothing to do with the album, which was inspired by a Dean Stockwell-Herb Berman screenplay, I liked to imagine that it was written to capture the feeling too often ignored by movies and music. The truth of loss that comes after the magic, after the bum-rush of serotonin and possibilities, after you realize the holes inside haven’t been plugged, that the overflow of emotion you poured in ran right out. —Jeff Gonick

9. Neil Young: After the Gold Rush (1970)Along with Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks, After the Gold Rush is one of the greatest break-up records ever made regardless of intention. Even though it has nothing to do with the album, which was inspired by a Dean Stockwell-Herb Berman screenplay, I liked to imagine that it was written to capture the feeling too often ignored by movies and music. The truth of loss that comes after the magic, after the bum-rush of serotonin and possibilities, after you realize the holes inside haven’t been plugged, that the overflow of emotion you poured in ran right out. —Jeff Gonick

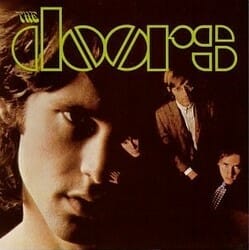

8. The Doors: The Doors (1967)The Doors’ 1967 self-titled debut catapulted the Los Angeles four-piece from house band at the Whiskey A Go-Go into the national spotlight. Though their rapid ascension can be attributed to the success of singles “Light My Fire” and “Break On Through (To The Other Side),” the album is full of gems from start to finish, culminating with “The End,” a chilling 11-minute, 43-second Oedipal examination that was as much a performance piece as it was a song. Morrison and The Doors would grow beards and foray into more blues-based material in the ’70s, but The Doors will always be the album they are most remembered for. —Ryan Bort

8. The Doors: The Doors (1967)The Doors’ 1967 self-titled debut catapulted the Los Angeles four-piece from house band at the Whiskey A Go-Go into the national spotlight. Though their rapid ascension can be attributed to the success of singles “Light My Fire” and “Break On Through (To The Other Side),” the album is full of gems from start to finish, culminating with “The End,” a chilling 11-minute, 43-second Oedipal examination that was as much a performance piece as it was a song. Morrison and The Doors would grow beards and foray into more blues-based material in the ’70s, but The Doors will always be the album they are most remembered for. —Ryan Bort

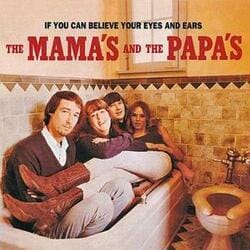

7. The Mamas & the Papas: If You can Believe Your Eyes and Ears (1966)California, land of Ronald Reagan and P. F. Sloan, deserves the credit for latching on to these four wanderers long enough to record them and turn them into superstars. Appropriately, their first single, “California Dreamin’,” is a paean to that state, and is still, for my money, the finest song they have recorded. The very concept of the song (“California dreamin’ on such a winter’s day”) is evocative; but it is the execution of the song that makes it a masterpiece. The Mamas and the Papas are extremely sensitive to their material and to the impact of their finished product (producer Lou Adler probably deserves quite a bit of the credit here); their whole gimmick, if you want to call it that, is complex harmonies, each group member singing on one or several tracks which, when all mixed together, produce a new sort of harmony, not at all choral. The ancient concept of the round figures importantly, as do the very modern innovations of the Beatles and the Beach Boys. The impact of this harmonic style, used effectively, is wondrous: “California Dreamin’” changes from a still image into a movie of emotion, tapping the listener on the shoulder and swirling him through the singers’ world. And the vocal is framed with precision and love by the instrumental solos: guitar at the opening, electric violin and flute in the middle of the song. The poignant effect of the flute is a tribute both to the orchestration and to John Phillips, who arranged (and wrote) the song. —Paul Williams

7. The Mamas & the Papas: If You can Believe Your Eyes and Ears (1966)California, land of Ronald Reagan and P. F. Sloan, deserves the credit for latching on to these four wanderers long enough to record them and turn them into superstars. Appropriately, their first single, “California Dreamin’,” is a paean to that state, and is still, for my money, the finest song they have recorded. The very concept of the song (“California dreamin’ on such a winter’s day”) is evocative; but it is the execution of the song that makes it a masterpiece. The Mamas and the Papas are extremely sensitive to their material and to the impact of their finished product (producer Lou Adler probably deserves quite a bit of the credit here); their whole gimmick, if you want to call it that, is complex harmonies, each group member singing on one or several tracks which, when all mixed together, produce a new sort of harmony, not at all choral. The ancient concept of the round figures importantly, as do the very modern innovations of the Beatles and the Beach Boys. The impact of this harmonic style, used effectively, is wondrous: “California Dreamin’” changes from a still image into a movie of emotion, tapping the listener on the shoulder and swirling him through the singers’ world. And the vocal is framed with precision and love by the instrumental solos: guitar at the opening, electric violin and flute in the middle of the song. The poignant effect of the flute is a tribute both to the orchestration and to John Phillips, who arranged (and wrote) the song. —Paul Williams

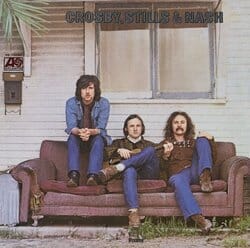

6. Crosby, Stills & Nash: Crosby Stills & Nash (1969)The self-titled debut album from this supergroup made up of former members of The Byrds, Buffalo Springfield and The Hollies starts with the flooring and intricate harmonies on “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes” and doesn’t let up. While their musicianship—blending the rootsy sounds of blues, jazz, country and folk—was undeniable, Crosby, Stills & Nash’s legacy is also heavily politically vibrant. Later albums would include responses to police brutality during peaceful protests, but their involvement with activism stems from “Long Time Gone”—a response to the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy. The reflection of their bold viewpoints begins on this friendly pop-medley album that became a cornerstone and a launching point for many musicians’ activism. —Adam Vitcavage

6. Crosby, Stills & Nash: Crosby Stills & Nash (1969)The self-titled debut album from this supergroup made up of former members of The Byrds, Buffalo Springfield and The Hollies starts with the flooring and intricate harmonies on “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes” and doesn’t let up. While their musicianship—blending the rootsy sounds of blues, jazz, country and folk—was undeniable, Crosby, Stills & Nash’s legacy is also heavily politically vibrant. Later albums would include responses to police brutality during peaceful protests, but their involvement with activism stems from “Long Time Gone”—a response to the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy. The reflection of their bold viewpoints begins on this friendly pop-medley album that became a cornerstone and a launching point for many musicians’ activism. —Adam Vitcavage

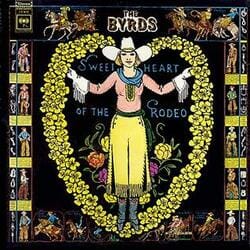

5. The Byrds: Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1968)Considered the definitive moment when hippie rock met country, Sweetheart of the Rodeo marked Chris Hillman’s buddy Gram Parsons joining the band that defined folk-rock with “Turn! Turn! Turn!” and Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man.” Suddenly aligned with a hardcore right-wing genre, stereotypes were shattered—not with Clarence White’s electric guitar, but pools of Jay Dee Maness and Lloyd Green’s plangent steel. Songs from bluegrass stalwarts The Louvin Brothers (“The Christian Life”), hard folkie Woody Guthrie (“Pretty Boy Floyd”) and emerging superstar Merle Haggard (“Life in Prison”) sat comfortably beside Dylan (“You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere”) and Tom Hardin (“You’ve Got A Reputation”) as simpatico companions, making the synthesis seamless. Parsons’ enduring “Hickory Wind,” a wistful song of time spent growing up, embodies what’s to come, stands out along with his “100 Years From Now.” Considered a failure when it was released, the visionary adaptation of country & western with California rock and pop paved the way for The Eagles, Linda Ronstadt, Poco and Emmylou Harris. —Holly Gleason

5. The Byrds: Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1968)Considered the definitive moment when hippie rock met country, Sweetheart of the Rodeo marked Chris Hillman’s buddy Gram Parsons joining the band that defined folk-rock with “Turn! Turn! Turn!” and Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man.” Suddenly aligned with a hardcore right-wing genre, stereotypes were shattered—not with Clarence White’s electric guitar, but pools of Jay Dee Maness and Lloyd Green’s plangent steel. Songs from bluegrass stalwarts The Louvin Brothers (“The Christian Life”), hard folkie Woody Guthrie (“Pretty Boy Floyd”) and emerging superstar Merle Haggard (“Life in Prison”) sat comfortably beside Dylan (“You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere”) and Tom Hardin (“You’ve Got A Reputation”) as simpatico companions, making the synthesis seamless. Parsons’ enduring “Hickory Wind,” a wistful song of time spent growing up, embodies what’s to come, stands out along with his “100 Years From Now.” Considered a failure when it was released, the visionary adaptation of country & western with California rock and pop paved the way for The Eagles, Linda Ronstadt, Poco and Emmylou Harris. —Holly Gleason

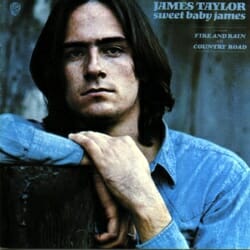

4. James Taylor: Sweet Baby James (1970) James Taylor is hard to dislike. There’s an earnest warmth to all of his music. Sure, it’s inoffensive and always well-meaning, but even most curmudgeons will admit to being charmed by his soft-hearted tunes. His music is a crucial part of the fabric of American culture—I mean, who among us has parents, aunts and uncles or grandparents that don’t adore Taylor? Taylor made introspective, folky soft rock that helped define the modern singer/songwriter tradition. By the early ‘70s, the dust hadn’t yet settled after such a revolutionary decade, and intergenerational discord still remained, but apolitical music with wide-ranging appeal still had its place. Taylor’s 1968 debut album underperformed commercially, but the follow-up, Sweet Baby James, arrived two years later, sold millions of copies and kickstarted his decades-long career. One reason an album like Sweet Baby James didn’t appear tone-deaf in spite of the times was because of Taylor’s raw depiction of his inner demons. Taylor struggled with drug addiction and depression, two factors that led to his exemption from serving in the Vietnam War, and he sings of these pains on songs like “Steamroller Blues” and “Sunny Skies.” While following deeply American traditions of singing personal tales about overcoming darkness, the music was also unabashedly rootsy, but it blended influences well enough that it still felt fresh. With its slightly twangy acoustic pop sound, it’s Taylor’s best album for a melancholic Sunday stroll—and his finest album, period. —Lizzie Manno

James Taylor is hard to dislike. There’s an earnest warmth to all of his music. Sure, it’s inoffensive and always well-meaning, but even most curmudgeons will admit to being charmed by his soft-hearted tunes. His music is a crucial part of the fabric of American culture—I mean, who among us has parents, aunts and uncles or grandparents that don’t adore Taylor? Taylor made introspective, folky soft rock that helped define the modern singer/songwriter tradition. By the early ‘70s, the dust hadn’t yet settled after such a revolutionary decade, and intergenerational discord still remained, but apolitical music with wide-ranging appeal still had its place. Taylor’s 1968 debut album underperformed commercially, but the follow-up, Sweet Baby James, arrived two years later, sold millions of copies and kickstarted his decades-long career. One reason an album like Sweet Baby James didn’t appear tone-deaf in spite of the times was because of Taylor’s raw depiction of his inner demons. Taylor struggled with drug addiction and depression, two factors that led to his exemption from serving in the Vietnam War, and he sings of these pains on songs like “Steamroller Blues” and “Sunny Skies.” While following deeply American traditions of singing personal tales about overcoming darkness, the music was also unabashedly rootsy, but it blended influences well enough that it still felt fresh. With its slightly twangy acoustic pop sound, it’s Taylor’s best album for a melancholic Sunday stroll—and his finest album, period. —Lizzie Manno

3. Crosby Stills Nash & Young: Déjà Vu (1970)  With the follow-up to Crosby, Stills & Nash’s critically acclaimed debut, the group decided to enlist the talents of Canadian singer/songwriter Neil Young. All of the group’s members, including Young, had already established themselves as musical powerhouses through their work with previous bands Buffalo Springfield (Stills and Young), The Byrds (Crosby), and The Hollies (Nash), and all were on the verge of launching successful solo careers as well. With the addition of Young, CSN gained an extra voice to add to their already complex tidal waves of harmony as well as another unique songwriter. The result turned the band that is often cited as one of the first supergroups into something even better. Despite the tensions within the band that stunted their potential over the following years, the fusion of country/folk songwriting with psychedelic/hippie flair and pop sensibility caused Déjà Vu to become a standout record of its time and the diamond of the group’s catalog. —Wyndham Wyeth

With the follow-up to Crosby, Stills & Nash’s critically acclaimed debut, the group decided to enlist the talents of Canadian singer/songwriter Neil Young. All of the group’s members, including Young, had already established themselves as musical powerhouses through their work with previous bands Buffalo Springfield (Stills and Young), The Byrds (Crosby), and The Hollies (Nash), and all were on the verge of launching successful solo careers as well. With the addition of Young, CSN gained an extra voice to add to their already complex tidal waves of harmony as well as another unique songwriter. The result turned the band that is often cited as one of the first supergroups into something even better. Despite the tensions within the band that stunted their potential over the following years, the fusion of country/folk songwriting with psychedelic/hippie flair and pop sensibility caused Déjà Vu to become a standout record of its time and the diamond of the group’s catalog. —Wyndham Wyeth

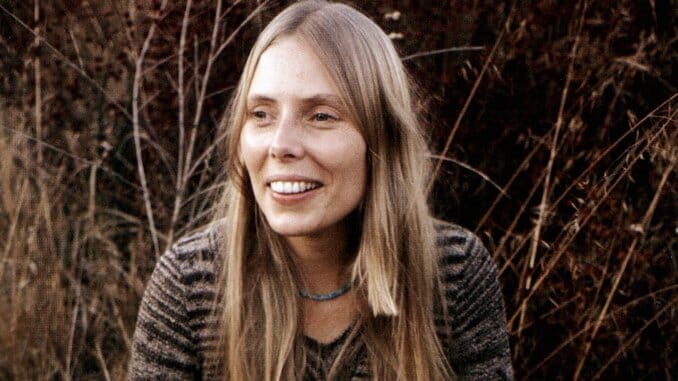

2. Joni Mitchell: Ladies of the Canyon (1970) The title track of Joni Mitchell’s 1970 album Ladies Of The Canyon describes three women. They lived in Laurel Canyon, up in the Hollywood Hills, along a mountain gorge that had long been a bohemian refuge not far from Sunset Strip. In the late ’60s, folk and rock ‘n’ roll musicians began moving into the cheap cottages on the dead-end streets branching off Laurel Canyon Boulevard. Mitchell lived in one such home with her then-lover Graham Nash, who immortalized it as “a very, very, very fine house with two cats in the yard” and who has always insisted he first sang with David Crosby and Stephen Stills in that cottage. There was a lot of sex and drugs going on, but we’ll leave those stories to the anthropologists. What endures from that time is a particular kind of music, a reaction to the urban, street-corner masculinity of most rock ‘n’ roll before 1970. By contrast, the Laurel Canyon Sound was rural, domestic and feminine, full of introspective lyrics, twangy wood instruments and pillowy vocal blends. And Mitchell was the genre’s true genius. One of the women in the song “Ladies of the Canyon,” was Trina (loosely based on cartoonist/artist Trina Robbins), who embroidered her second-hand coat with leaves and vines. Yes, it was beautiful, but is this “antique luxury” rebellion or middle-class privilege? Annie (loosely based on the Mamas and Papas’ Cass Elliot) fed every stray who walked in—feral cat or male musician, it didn’t matter. But was this maternal magnanimity or servile co-dependence? Estrella (loosely based on Mitchell herself) hurled “songs like tiny hammers” at “beveled mirrors in empty halls.” The domestic sphere of women deserves attention, she implied, but at what point does it become merely insular? With such questions, Mitchell pushed the boundaries of the Laurel Canyon Sound as far as it could go. —Geoffrey Himes

The title track of Joni Mitchell’s 1970 album Ladies Of The Canyon describes three women. They lived in Laurel Canyon, up in the Hollywood Hills, along a mountain gorge that had long been a bohemian refuge not far from Sunset Strip. In the late ’60s, folk and rock ‘n’ roll musicians began moving into the cheap cottages on the dead-end streets branching off Laurel Canyon Boulevard. Mitchell lived in one such home with her then-lover Graham Nash, who immortalized it as “a very, very, very fine house with two cats in the yard” and who has always insisted he first sang with David Crosby and Stephen Stills in that cottage. There was a lot of sex and drugs going on, but we’ll leave those stories to the anthropologists. What endures from that time is a particular kind of music, a reaction to the urban, street-corner masculinity of most rock ‘n’ roll before 1970. By contrast, the Laurel Canyon Sound was rural, domestic and feminine, full of introspective lyrics, twangy wood instruments and pillowy vocal blends. And Mitchell was the genre’s true genius. One of the women in the song “Ladies of the Canyon,” was Trina (loosely based on cartoonist/artist Trina Robbins), who embroidered her second-hand coat with leaves and vines. Yes, it was beautiful, but is this “antique luxury” rebellion or middle-class privilege? Annie (loosely based on the Mamas and Papas’ Cass Elliot) fed every stray who walked in—feral cat or male musician, it didn’t matter. But was this maternal magnanimity or servile co-dependence? Estrella (loosely based on Mitchell herself) hurled “songs like tiny hammers” at “beveled mirrors in empty halls.” The domestic sphere of women deserves attention, she implied, but at what point does it become merely insular? With such questions, Mitchell pushed the boundaries of the Laurel Canyon Sound as far as it could go. —Geoffrey Himes

1. Carole King: Tapestry (1971)With Tapestry, Carole King grapples with the grief, anger and—eventual—hope at the end of a relationship with devastating honesty. Following her divorce from husband and songwriting partner Gerry Goffin, King left New York for Laurel Canyon where she met Joni Mitchell and James Taylor (i.e., Two More Singer-Songwriters Here to Emotionally Wreck You) who encouraged her to perform on her own album. The pair sang backup on Tapestry, which features both originals and covers that King had co-written with Goffin during their marriage, like her ugly cry-inducing version of “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow?” From the album’s bare bones cover (featuring King and her cat Telemachus, added for the last photo of the shoot) to her aching lyrical talents (just try to keep a dry eye during “Way Over Yonder”), King’s vulnerability is startling—and wholly responsible for the album’s resonate lasting power. —Katie Cameron

1. Carole King: Tapestry (1971)With Tapestry, Carole King grapples with the grief, anger and—eventual—hope at the end of a relationship with devastating honesty. Following her divorce from husband and songwriting partner Gerry Goffin, King left New York for Laurel Canyon where she met Joni Mitchell and James Taylor (i.e., Two More Singer-Songwriters Here to Emotionally Wreck You) who encouraged her to perform on her own album. The pair sang backup on Tapestry, which features both originals and covers that King had co-written with Goffin during their marriage, like her ugly cry-inducing version of “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow?” From the album’s bare bones cover (featuring King and her cat Telemachus, added for the last photo of the shoot) to her aching lyrical talents (just try to keep a dry eye during “Way Over Yonder”), King’s vulnerability is startling—and wholly responsible for the album’s resonate lasting power. —Katie Cameron