Though he died 31 years ago, Doc Pomus is back on the radar. Bob Dylan’s new book, The Philosophy of Modern Song, is dedicated to Pomus. One of the longest chapters in Peter Guralnick’s excellent recent book, Looking To Get Lost, is devoted to the songwriter. In recent years, Pomus’s most famous song, “Save the Last Dance for Me,” has been recorded by country superstar Eric Church and jazz guitarist Bill Frisell. The past dozen years have seen Pomus’s songs recorded by Lake Street Dive, Diana Krall, Mick Hucknall, Aaron Neville and Chris Isaak.

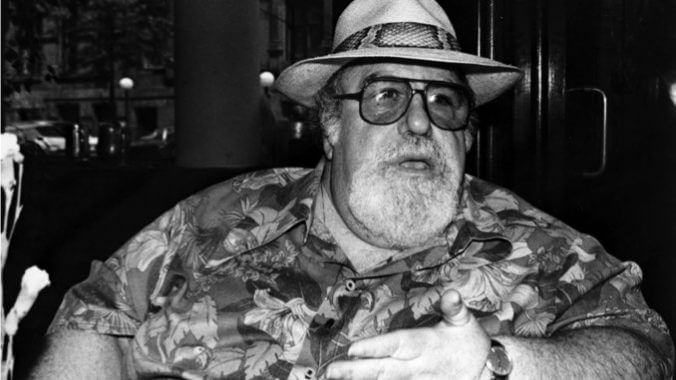

Much of the Pomus legend rests on his reputation as a master raconteur. In the final decade of his life, he was often found at a back table in a Manhattan nightclub, holding court with his colorful tales of encounters with John Lennon, Lou Reed, Colonel Tom Parker and Jerry Wexler and his profane opinions on modern rock ’n’ roll. He was a charismatic figure, no doubt, but what he should really be remembered for are his lyrics.

Like so many musical wordsmiths of his generation, he was a child of the Great Depression who found the best mirror for the situation to be the African-American blues, an art form that was as underappreciated as it was overachieving. Here was a literature that placed a premium on both musicality and economy in language. It was a form of verse that acknowledged the fundamental difficulty and unfairness of life but asserted that it was possible to survive—maybe even find laughter and love.

Pomus served a long apprenticeship on this circuit, writing songs for his own singles recorded for nearly every small blues label in New York. The general public didn’t pay much attention, but other performers and songwriters appreciated what he was doing. Ray Charles, LaVern Baker, Jimmy Witherspoon and Big Joe Turner all recorded some of the youngster’s tunes.

He had mastered the form, but he needed to make more money. What if he tried his hand at this new fad called rock ’n’ roll? Could you blend the clear-eyed realism of an adult music like the blues with the rosy-eyed romanticism of teenage pop? This wasn’t an easy problem to solve, but Pomus’s ability to do so is what makes him one of the great wordsmiths of rock ’n’ roll’s first generation.

Pomus often told the story of how he wrote 1959’s “Teenager in Love,” which became the signature song for Dion & the Belmonts. “It was originally going to be ‘(It’s Great To Be) Young and in Love.,’” he told journalist Pat Hackett in 1986. “But then I got the concept that it was actually tough to be young and in love. I was starting to get that whole feeling toward young people’s misery and love. So I changed it to ‘(Why Must I Be a) Teenager in Love?’”

That was his secret: He wrote the teenage blues. He wrote about adolescence not as most people wanted to imagine it but as it actually was. As Dion DiMucci sang, “One day I feel so happy; next day I feel so sad…. Every night I ask the stars up above: Why must I be a teenager in love?” The music behind the words merely amplified this paradox of ecstasy and despair.

Pomus’s evolution into storytelling is obvious on 1960’s “Save the Last Dance for Me.” The title line in the chorus seems to be a pledge of romantic loyalty, but the verses tell a different story. “You can dance every dance with the guy who gave you the eye,” sings the Drifters’ Ben E. King, “let him hold you tight.” It’s a blues about tolerating small amounts of disloyalty as long as the ultimate loyalty remains. It’s a recognition of emotional trade-offs that often occur in the blues but seldom in teenage pop. “Don’t forget who’s taking you home,” King sings in the chorus, “and in whose arms you’re gonna be.”

The push-and-pull Cuban rhythm that Shuman engineered for the song reinforced the romantic sentiment of the chorus, leaving it to the catch in King’s vocal to reveal the anxiety of the verses. Alex Halberstadt, who wrote the fine biography, Lonely Avenue: The Unlikely Life & Times of Doc Pomus, in 2007, reveals that Pomus wrote the lyrics when a wedding invitation reminded him of his own wedding, when he had to watch his new bride dance with everyone but himself. But the finished song transcended any specific incident to speak to anyone juggling trust and doubt about a lover.

“One of the problems with the singer/songwriter,” he told Guralnick, “is that he writes songs according to the way he sings. So, often those songs are not going to be recorded by anyone else; they just don’t have a life. Now, you take a song like ‘Save the Last Dance for Me,’ or any of the Latin songs that Mort and I wrote together, I was trying to get the lyrics to sound like a translation,… to bring the thing back to some elemental point.”

“Save the Last Dance for Me” didn’t fit the formula for teenage wish fulfillment, and Atlantic Records consigned it to the B-side of a Drifters’ single, “Nobody but Me.” It took Dick Clark, of all people, to recognize that the blues-tinged drama of “Save the Last Dance for Me” was more likely to resonate with the audience. He urged the label to flip the 45 over and promote the B-side instead. They did, and it spent three weeks at #1 on the pop chart. And it proved so adaptable that both Emmylou Harris and Dolly Parton scored top-10 country singles with the song, in 1979 and 1983 respectively.

RCA made the same mistake with another Pomus masterpiece of teenage blues. “Suspicion” is the confession of a boy who keeps tormenting himself about his lover’s true feelings. “Every time you call me and tell me we should meet tomorrow,” Elvis Presley sang in 1962 over a push-and-pull Latin big-band arrangement, “I can’t help but think that you’re meeting someone else today…. Suspicion torments my heart; suspicion keeps us apart.” Presley’s light, moody baritone captures the ambivalence of Pomus’s words: he wants to believe the best, but he can’t stop thinking about the worst.

RCA shied away from such a complicated tangle of emotions, relegating the song to the B-side of the more straightforward “Kiss Me Quick” (also by Pomus and Shuman). As a result Presley’s “Suspicion” peaked at #103 on the Billboard chart. Two years later Terry Stafford recorded a close copy of the Presley record and was rewarded with a #3 pop hit.

The Stafford version was a solid performance, but no one sang like Presley. His gorgeous baritone could glide through any song—blues, country, gospel, rock ’n’ roll, disposable pop—and coax every drop of pleasure out of the melody. But beneath the surface of the obvious emotion—whether a lament about mistreatment or a plea for fuller love—there was always an implied chuckle, as if he were amused by the whole situation. You could act like a hound dog; you could try to step on his blue suede shoes, but he just couldn’t take you seriously as a threat.

And that’s why Presley’s records had a sense of freedom that none of his influences had. Think about it: Are you freer if you’re angry at the person who did you wrong or if you’re laughing at that person? Presley sang as if he were so liberated, he was beyond any attempts to fence him in or bring him down. For this to work, he needed songs that hinted at both the wound and the chuckling resiliency. Pomus, Shuman, Leiber and Stoller provided those songs.

“You know people always talk about the different influences he had,” Pomus told interviewer Mojo Nixon in 1989, “but the truth of the matter is he was an original. And like I have always told people, the one thing about getting Elvis Presley [to] record [one of my songs], that always meant that you were gonna hear your song plus, because he always put something in the song that maybe you never heard…. I always anticipated the Presley record because you would get something in that song you never dreamed of.”

A great example of this is 1961’s “(Marie’s the Name) His Latest Flame.” As he listens to a friend describing a new love, the narrator gradually realizes that it’s the same woman he was with last night. “I wished him luck and then he said goodbye,” Presley sang in the chorus. “He was gone but still his words kept returning. What else was there for me to do but cry?” He says he’s crying, but the jauntiness of the vocal suggests that he got over it fairly quickly. Presley and his ghostwriter Pomus are suggesting that, yes, setbacks sting, but if you can appreciate the absurdity of human nature, you can recover quickly and move on.

Born as Jerome Solon Felder in Brooklyn in 1925, the boy who would take the stage name of Doc Pomus had a gift for language. He could wage the battle of insults known as “playing the dozens” with quick-witted, razor-tongued triumph. He could make up his own lyrics to the pop and blues songs he heard on the radio. He tested near the top of IQ spectrum. He would eventually win his first wife, actress Willi Burke, by composing dozens of romantic poems that he would slip under her door.

If he had been born in a different era, into a different economic class or with a different body, he might have gone to a top college and become a conventional writer: a novelist, poet or journalist. As it was, however, he grew up in the Great Depression in a working-class Jewish ghetto with a body crippled by an early bout of polio and an iceball attack that left his hand numb. So he would apply his nascent verbal talent to the literature he liked best: blues songs.

As he recovered from polio, he was homeschooled for most of elementary and junior high school. That isolation led to a voracious appetite for books and to an outsider’s perspective on the world beyond his parents’ apartment window. Both factors were crucial in making him a writer. He longed to be part of the stickball games and dances going on on the other side of the pane—and in high school he’d rejoin that world. But he would never completely belong, and that detached perspective was essential to the musical stories he would author.

Pomus’s first breakthrough hit was “Lonely Avenue,” which Ray Charles turned into a #6 R&B hit in 1956. It’s a song that draws from the writer’s childhood solitude but transforms it into metaphors that any person can relate to, whether the listener is blind like Charles or heartbroken like a teenager in love. The narrator claims he lives on Lonely Avenue, in an apartment where, “My covers they feel like lead, and my pillow feels like stone. I’ve tossed and turned so every night. I’m not used to being alone.”

Life changed for Jerry Felder at 15 when he bought Big Joe Turner’s “Piney Brown Blues” in 1940 from a neighborhood record shop. Turner had a baritone of oceanic fullness and fluid ease, and his words condensed experiences into a handful of words that clarified the message of the music even as the language gained power from the sound. A long night of clubbing was summed up as “Little boys jump and swing into the broad daylight” and the beginning of romance as “I want to tell you why I love you: Because you understand everything that I do.”

“That to me was everything music was supposed to be,” Pomus told Guralnick. “It was the way the male voice was supposed to sound. I can’t explain. I never even knew there was music like that. It was the transformation of my life. Up until then, my family was dead set on my becoming a lawyer or accountant, something safe…. From the moment that I heard Joe Turner sing, though, I knew what I wanted to be. I was going to be a blues singer.”

Here was a channel for his literary ambitions. The blues provided countless examples of speaking frankly about poverty, lust, death and ostracism. The flatted notes echoed the pain of rejection, and syncopated rhythms promised triumph over that same denial. Moreover, the blues were often assembled in modular fashion; each stanza was independent and could be added, subtracted or moved at will. New verses and old could be sung over the same music, sliding in and out at the singer’s discretion and rearranged on a moment’s inspiration. This was the perfect entry vehicle for a singer who was becoming a songwriter.

By the time Pomus was a high school senior, he was taking the subway to Greenwich Village, climbing with his crutches onto the stage at George’s, a popular jazz club, and singing “Piney Brown Blues” with the band. It’s easy to imagine the skepticism of the black musicians on stage and the black members of the audience as this gimpy white kid struggled to the microphone. It’s just as easy to imagine their surprise when, leaning on his crutches, he channeled Big Joe Turner through an unlikely body.

At first, he was just a novelty—a Jewish teenager with braces on his legs belting out hard-core blues—but soon there was a grudging respect and an invitation to keep coming back. And he did, adding more popular blues songs of the era—and adding his own verses to those songs. One night Lester Young, perhaps the finest saxophonist of the day, sat in behind the adolescent now calling himself Doc Pomus.

We can hear what he sounded like on the singles and live tapes from that period. At this point, he was a good but not great singer and a promising but improving songwriter. He was working a lot but making little money. He was living in fleabag apartments and about to get married. Something had to change. Maybe a short, barrel-shaped Jewish kid was never going to become big-time blues singer. Maybe he was destined to be a behind-the-scene lyricist in the great Jewish tradition of Irving Berlin, Ira Gershwin and Jerry Leiber.

He sent a demo of a song called “Young Blood” to Leiber and Stoller and heard nothing about it. So he was shocked when he put a nickel in a jukebox to play the Coasters’ “Young Blood,” only to discover it was his old song, substantially rewritten by his two role models. He was even more shocked when he got a royalty check for $1500.

As he quit live performing in 1957 to devote more and more time to songwriting, he realized he needed some help. Two years earlier, he had hired Shuman, a 17-year-old kid who was dating Pomus’s cousin, to be a pianist and assistant. He began by giving Shuman 10% of the songs they wrote. As they began having more and more success, Pomus upped the percentage until they were finally 50/50 partners.

They were a good match. Pomus could make up blues verses at will and belt them out with gusto to one blues tune or another. Shuman could come up with rocking piano parts and thread his older partner’s stanzas into a song. More important, Shuman had good grasp of the bluesy shuffles and chirpy melodies that were filling the jukeboxes with rock ’n’ roll hits. This teenage scene was foreign territory for Pomus, who was already in his 30s, but he quickly got the hang of it.

Otis Blackwell, Pomus’s old buddy from the Brooklyn blues clubs, had a good grasp of it as well and was scoring hits such as “Elvis Presley’s “Don’t Be Cruel,” Jerry Lee Lewis’s “Great Balls of Fire” and Little Willie John’s “Fever.” Blackwell offered to introduce Pomus and Shuman to his song publishers at Hill & Range, the company that had a deal with Colonel Tom Parker to supply most of Presley’s material.

Without much of a track record, Pomus and Shuman were signed and assigned to come up with songs for Fabian, a photogenic crooner with a shaky command of pitch. The two writers gave him an uptempo song, “Turn Me Loose,” that was so good even Fabian couldn’t mess it up. Soon Pomus and Shuman were working with the Mystics (“Hushabye”), Dion & the Belmonts (“A Teenager in Love”) and Bobby Darin (“Plain Jane”).

But crooners like Darin and Bobby Vee shied away from the tricky phrasing that Shuman was cooking up for Pomus lyrics like “Little Sister” and “(Marie’s the Name of) His Latest Flame.” So when the call finally came from the Presley camp to pitch some songs as a follow-up to their first Presley cut, “A Mess of Blues,” they offered these two songs. Presley had no trouble with them and soon they were a double-A-sided single that put both songs into the top 10. In all, Presley would eventually record 17 of the duo’s compositions.

Equally profitably artistically—if not economically—was the songwriting team’s work with the Drifters. Their new friends, Leiber and Stoller, were producing the vocal group’s records and solicited new creations from Pomus and Shuman (and also from Carole King, Burt Bacharach and Cynthia Weil). Some of the latter duo’s greatest songs—“Save the Last Dance for Me,” “I Count the Tears,” “Sweets for My Sweet” and “This Magic Moment”—went to the Drifters, whose majestic work disproved the myth that rock ’n’ roll was a barren wasteland between Presley going into the army in 1958 and the Beatles landing in 1964 at New York’s newly christened Kennedy Airport.

In 1965, Pomus was on top of the world when multiple tragedies struck at roughly the same time. He accidentally tumbled out of his wheelchair and tore his ligaments in both knees. While he was in the hospital, Shuman announced he was ending their partnership and moving to France. A few days later, Burke announced that she was leaving him. Soon after that Pomus found that his father was in the same hospital after suffering a heart attack. The son was convinced that his life as he’d known it was over.

He withdrew from the music business and supported himself as a professional gambler for 10 years. But as that business grew more and more violent in the mid ’70s, he left that behind too. He’d kept writing on the side, but he was having even less luck there than at the card table. Things turned around, however, in 1981, when five of the songs Pomus had been writing with Mac “Dr. John” Rebennack were picked for a new B.B. King album, There Must Be a Better World Somewhere. Rebennack was the pianist, and two Ray Charles alumni were playing saxophone. The results sparkled and the record won a Grammy.

The title track was a slow blues, an older man’s lament that the world is stacked against the little guy: “Flying high, some joker clips my wings just ’cause he gets his kicks doing those kind of things.” King’s raspy, world-weary voice echoes every lesson learned in the school of hard knocks, and Hank Crawford’s also sax echoes the lyrics with high wails of exasperation. Despite it all, though, Pomus’s narrator refuses to give up his faith that somehow, sometime, somewhere he’ll find a better world.

“Here again,” Pomus told Guralnick, “this has a lot to do with my philosophy about the way things are, or at least the way things are for me personally…. If you’re leading a certain kind of life, these are the kind of songs you’re gonna write. It’s like you’re fighting heavyweight champions with one arm tied behind your back. I think everyone involved with the blues, or singing the blues, feels like that.”

There would be more late-career collaborations with Dr. John, Mink DeVille and Big Joe Turner. Pomus was working on a new project when he died on March 14, 1991. When that album, Johnny Adams Sings Doc Pomus: The Real Me, emerged later that year, it proved one of the peaks of the songwriter’s career.

Adams was one of New Orleans’ finest vocalists, ranking right up there with Aaron Neville and Irma Thomas, and this record (plus a similar album of Percy Mayfield songs) showcased him at his very best. Producer Scott Billington resisted the temptation to do Pomus’s most famous songs but focused instead on overlooked gems and newly composed numbers that should’ve been famous—seven of the 11 tracks came from the Pomus-Rebennack partnership. Unlike so many of his peers, Pomus went out in full possession of his powers.

And four years after his death, 14 of his celebrity admirers contributed to one of the better tribute albums ever made: Till the Night Is Gone: A Tribute to Doc Pomus. Especially memorable were vocal performances by Bob Dylan (Joe Turner’s “Boogie Woogie Country Girl”), Solomon Burke (Jimmy Witherspoon’s “Still in Love”), B.B. King (Adams’s “Blinded by Love”), Levon Helm (the Coasters’ “Young Blood”), John Hiatt (Elvis Presley’s “A Mess of Blues), Dion (Fabian’s “Turn Me Loose”), Rosanne Cash (the Drifters’ “I Count the Tears”), Aaron Neville (the Drifters’ “Save the Last Dance for Me”), and Irma Thomas (B.B. King’s “There Must Be a Better World Somewhere”).

If you map out those names on a timeline, you get a sense whose example Pomus drew from, which contemporaries he collaborated with and which younger artists he influenced. That’s a map of the immense nation of Pomus. That’s where that better world can be found.