The Curmudgeon: Is There Room in Rock ‘n’ Roll for a Second Act?

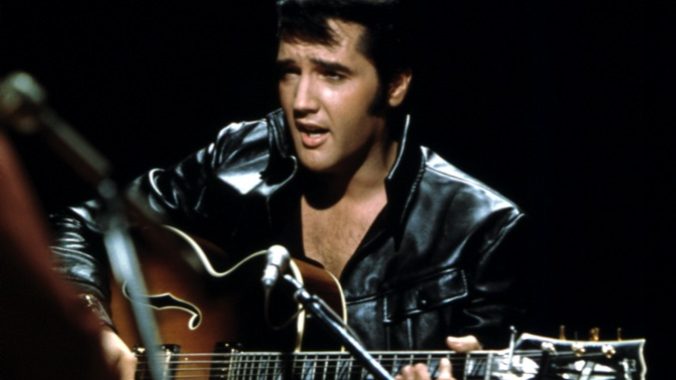

Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Music Features Elvis Presley

I’ll admit it. I enjoyed Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis movie, despite its many flaws. As history, it’s unreliable. But as fable, it’s true, even stirring. Actor Austin Butler is thoroughly convincing as the hero of the fairy tale: the young knight who leaves home to slay the dragons of American culture, who triumphs, then fails, then triumphs again, then fails again. Luhrmann’s over-the-top mise en scene provides the grandeur such a myth deserves.

I was especially interested in the “triumphs again” section of the film, for pop music in general—and rock ’n’ roll in particular—offer few examples of successful second chances. For most artists, the conjunction of fertile creativity and popular acceptance lasts for a while and then it’s over for good.

That window might be as narrow as a fluke single by such one-hit wonders as the Knickerbockers, Dionne Farris and Afroman or as long as the extended winning streaks by the Rolling Stones, Neil Young or Aretha Franklin. But once those windows close, they usually stay closed. The artists may still be able to sell concert tickets, but audiences will shout out requests for the old songs and show little interest in the new.

This is often disappointing for the artist and audience alike, but it shouldn’t be surprising. For all of us, the period after we leave school for good is a time when we choose a path forward, a time when that choice is paramount in our lives. Unencumbered by marriage, children, school or mortgage, we can focus on both our creative ambitions and the hustle of making them happen. If we’re going to make great art that’s also popular, that’s when it’s going to happen.

Maybe the art is carpentry or community organizing, and maybe the popularity is confined to one city, but the dynamic is the same. If we can gain some traction in our 20s, maybe we can sustain that momentum for a decade or two. But as we accumulate the encumbrances enumerated above, it becomes harder and harder to bounce back from a crisis. And a crisis will always emerge. Maybe we can finesse it, but rarely can we regain that initial burst of creativity. And sometimes we make a bad decision—the equivalent of tying ourselves up in a bad Hollywood contract—and we fall off our perch.

Few artists have risen as fast or fallen as far as Presley. The Elvis movie captures the drama of this ascent and descent, even if it misrepresents its mechanism. Luhrmann is primarily a visual artist, so it was predictable that he’d attribute Presley’s success to the visual presentation—his pastel clothes and wiggling hips—and his failure to the suppression of that look and those moves.

But those were secondary factors. Presley’s triumph was primarily fueled by his entirely non-visual impact over the radio. Hearing that voice over the airwaves—perhaps the most thrilling, most carefree, most gravity-defying voice of the 20th century—was enough to change one’s life. The TV appearances were merely icing on the cake.

Between 1954 and 1958, Presley recorded 23 charting singles for Sun Records and RCA, four of them released after he was drafted into the U.S. Army on March 24, 1958. It was as densely packed an era of artistic creation as pop music had ever known. He made one terrific album, Elvis Is Back, when he got out of the service, but then disappeared into a black hole of formulaic movies.

Those films grew ever feebler—both dramatically and musically—as his manager Tom Parker and his movie producer Hal Wallis rushed them out to maximize profits. The pictures dispirited Presley and alienated his best songwriters. Luhrmann captures the aura of depression that hovered over this phase of Presley’s career—with the possibility of a second act seemingly unlikely.

But Presley pulled it off. Luhrmann’s version of this turnabout more or less resembles the truth. Parker signed a deal with NBC for a 1968 TV Christmas special, but Presley and director Steve Binder hijacked the project to create a dramatic rediscovery of the singer’s artistic vitality. A return to blues, gospel and country numbers reconnected Presley to his roots. And the live portion of the show, with Presley clad in black leather and singing in a boxing ring surrounded by close-up fans, was electrifying. There’s a reason that the show, officially called Singer Presents … Elvis, has been known ever since as “The ’68 Comeback Special.”

The soundtrack from the TV show kicked off a string of strong albums: From Elvis in Memphis, That’s the Way It Is, Elvis Country, From Memphis to Vegas/From Vegas to Memphis and On Stage. The latter two are from the 1969 and 1970 live shows he began performing after the comeback special. Both the studio and concert recordings feature a fired-up singer, a crackerjack band and a healthy dose of Southern roots music.

This rebirth was genuine, but it was destined not to last. Parker locked the artist into a long-term contract at the International Hotel in Las Vegas; Presley began to lose interest in a show that seldom departed from the script, and he increasingly relied on pills to keep going. It was a tragic end to a heroic career.

Now there is a new seven-disc box set called Elvis on Tour, titled after the 1972 documentary film directed by Pierre Adidge and Robert Abel. A DVD of that movie is included as well as a CD for each of four complete shows from the 1972 tour—three of them largely unreleased previously. Two more CDs document the tour rehearsals, most of which have been available before.

This was the year things began to go south for Presley. He was always an interesting singer, but these versions lack the spark and originality of the 1969-1970 live recordings. The bloated face, the wobbly moves and the erratic singing are already creeping in. You can tell he’s losing interest in the mostly unchanging setlist—rushing through some songs and coasting through others. It would get a lot worse in the coming years, but this box set is for completists only.

There are some nice moments: the gospel-flavored version of “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” the movie montages of his early career (put together by a young Martin Scorsese) and especially the backstage, impromptu gospel sing-alongs. But if you want to hear the evidence of the singer’s remarkable second act, check out the 1968-1971 albums mentioned above.

In 1996, Bob Dylan faced a career crisis not unlike Presley’s in 1968. He was never guilty of making bad Hollywood movies, though he did make an insufferable indie film (Renaldo and Clara) and a series of underwhelming albums such as 1988’s Down in the Groove and 1990’s Under the Red Sky. In 1996, the latter was his last collection of new, original songs, though he did release two fine albums of traditional folk and blues numbers in 1992 and 1993. He had become a great songwriter who hadn’t released any great songs since the 1989 album Oh Mercy.

But in 1996, Dylan began a batch of new songs—many of which emerged on the 1997 album Time Out of Mind, which constituted his own “comeback special.” Not only was this fresh material, but it offered a different kind of songwriting. Gone was the surrealist poetry and psychedelic/biblical imagery of his early recordings. In their place was a highly condensed form of short-story writing with deadpan, film-noir narration. One song, the 16-minute “Highlands,” felt like a feature film all by itself. He had not only reinspired himself, but he had also reinvented himself.

The new box set, Fragments: Time Out of Mind Sessions (1996-1997), documents just how fertile and radical this resurrection was. In addition to the 11 songs included on the actual album (included here in a revealing new mix) there are three more songs that emerged only later, plus a new take on the old folk song, “Water Is Wide.” Three additional discs offer alternate studio versions of the songs, while a fifth disc offers live versions. The box comes with a 100-page, hardback book.

This was a new Bob Dylan—and for a certain kind of listener, an irresistible one. He had to be born again; it was the only way he could escape the comparisons to his past. It was the only way he could reclaim his strengths without repeating himself. It was the only way he could sing about himself on the other side of 50. Converting to a new aesthetic proved more effective than converting to a new religion.

He largely abandoned one of his best tools, the poetic metaphor, and embraced instead fictional description. In most of these songs, the narrator is in motion. He’s walking through streets that are dead; his feet are tired and his brain is wired. He’s going down that dirt road till someone lets him ride. He’s wading through high muddy water. The sheriff has clicked cold irons on his wrists and taken him 20 miles out of town. Every day is the same; he’s out the door and farther away than before.

It could be 1931; it could be 1941; it could be 1961; it could be 1991. The stores are boarded up; barns are falling down; the skies are gray and rumbling; winds blow across the winter fields. He’s almost reached his destination, but still it’s just beyond his reach. He’s trying to get to heaven before they close the door; he’s getting nearer but he’s still a million miles from you. He’s standing in the doorway; it’s not dark yet but it’s getting there. He can only get there one step at a time; he doesn’t know how much longer he can wait. He crossed the river, but he stayed a day too long.

To record these songs, he rehired Daniel Lanois, the producer of Oh Mercy. The two men had clashed during those 1989 sessions, and the conflicts were worse during these 1996-97 sessions. In their individual memoirs, Dylan and Lanois acknowledge as much, and the box set’s liner notes make Lanois out to be the villain. That’s simplistic. After all, the producer coaxed the two best Dylan albums of the 1980s and 1990s out of a floundering artist.

Lanois’ versions of these songs emphasized the swampy, sepia, film-noir aspects of these songs, while Dylan’s versions—especially the new remix—emphasize the vocals, the bottom and the literary-noir aspect. The takeaway from the box set is that these songs are so strong that they are fascinating in many different contexts. Though the differences between the producer’s vision and the singer’s are real, they are smaller than the contrasts between the studio versions and the live versions included in the package. And the live tracks are fascinating too.

Of the three songs that didn’t make the final album, “Marchin’ to the City” is a minor gospel-blues. But “Mississippi,” which eventually surfaced on Love and Theft, was a terrific blues narrative with a great hook. Just as good was “Red River Shore,” a Celtic cousin to “Highlands,” the album’s 16-minute elaboration of Robert Burns’ poem, “My Heart Is in the Highlands.”

The two latter songs juxtapose the narrator’s current, troubled circumstances with a fondly remembered past, a utopia set in the Scottish hills or on the far shore of the river, a place as enchanting as the jangly Gaelic melody. The two tunes are rootsy, Americana versions of Brigadoon, the 1947 Broadway hit by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe about a Scottish Shangri-La. Frank Sinatra had the biggest hit from that show with “Almost Like Being in Love.” The singer was already on Dylan’s mind, resulting in the two Sinatra-esque songs from Time Out of Mind: ”Make You Feel My Love” and “’Til I Fell in Love with You.”

The Beach Boys had their own crisis of faith as the 1960s turned into the 1970s. In 1967, the band’s prime architect, Brian Wilson, abandoned his ambitious Smile project amid a nervous breakdown. Journalists had been hailing it as a rock ’n’ roll masterpiece that would out-Beatle the Beatles—and when it was finally released in 2004, those predictions were borne out. But in the wake of the forsaken masterwork, a new narrative took hold: the Beach Boys had peaked and were finished as a creative force.

The band needed a “comeback special” as much as Presley or Dylan. Unfortunately, the Beach Boys were never able to combine quality music and broad popularity again. When they made good records, no one paid attention. When people were paying attention, the band released mediocre work.

The notion that the Beach Boys had lost it was not supported by the facts. Smiley Smile, the stripped-down version of Smile that was finally released, wasn’t what people had been hoping for, but it was a splendid record nonetheless—and it did include the biggest single of the Beach Boys’ career: “Good Vibrations.” The follow-up, 1967’s Wild Honey, largely crafted by Brian and his brother Carl, was more confounding: a back-to-basics R&B record that was utterly delightful, yielding two top-40 singles.

The next two albums, 1968’s Friends and 1969’s 20/20, were patched-together affairs of new and old tracks, Brian and non-Brian compositions, containing scattered gems and filler, transparent attempts to disguise Brian’s reduced involvement. It was hard to deny the declining quality. Then along came 1970’s Sunflower, a strong album with impressive songs by Brian and his brother Dennis. Unfortunately, neither the album nor any of its singles charted in the top 100. The quality was there, but the band had lost its connection to the public.

The more desperately they grasped for a “comeback special,” the less convincing they were. To drum up some publicity, the 1971 album Surf’s Up was baited with two tracks rescued from the Smile project, supplemented by trendy but gimmicky songs about the environment and student protests. The publicity put the album in the top 30, but there was no disguising the lack of new songs from Brian.

The next album, Carl and the Passions—”So Tough,” didn’t get the same push, but it was a much better record. Two South African musicians, Blondie Chaplin and Ricky Fataar, spiced up the band’s line-up, and there were three strong new songs by Brian. “He Comes Down” was a captivating gospel number, and the rocking “Marcella” should have been a hit single but wasn’t.

A troubling pattern was developing. The band kept looking for angles to recapture the public’s interest, only to disappoint those who were lured in by the publicity. Then they would put out a high-quality album that would get ignored. In 1972 manager Jack Rieley convinced the band to pack up their studio and move to Amsterdam to record the album that was released as 1973’s Holland. But it wasn’t that strong an effort, despite Brian’s catchy single, “Sail on, Sailor,” and a seven-inch bonus disc of Brian’s children songs.

Three years later, the band released 15 Big Ones, pushing the storyline that this time Brian was really back. But he wasn’t, and the underwritten and underproduced tracks proved as much. An audience that felt betrayed by the hype paid no attention to the 1977 follow-up, The Beach Boys Love You, an absolute gem of an album, the last great studio album the band would ever release. Essentially created by Brian and Carl working on their own, the songs boasted the childlike charm of a Jonathan Richman or NRBQ project.

The Beach Boys never found their “comeback special,” though they made a lot of worthy music searching for it. The new box set, Sail on Sailor—1972, documents those efforts during the titular year. The original versions of Carl and the Passions—”So Tough” and Holland are included as are many alternate takes and outtakes. The four studio discs are supplemented by two discs that present a 1972 live show at Carnegie Hall that was recorded for possible release but never saw the light of day till now.

Included are demos of songs that Brian started but never finished. The most interesting is a jigsaw-puzzle mash-up of Steve Winwood’s “Gimme Some Lovin’” and Brian’s “I Need Your Love.” But the six CDs offer nothing that might have saved the day and kept the band from morphing into an oldies act. There was no second act for them.