Arguing About Old Music

In the streaming era, greatest-hits collections have become, first and foremost, arguments about musical history. Here are some of the more compelling recent cases

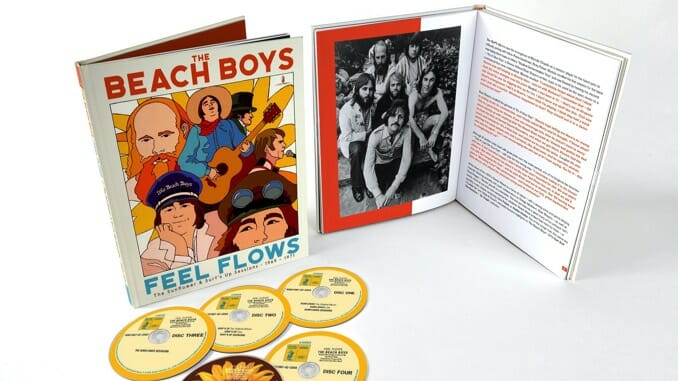

Image courtesy of Capitol/UMe Music Features Greatest Hits

In the last century, most reissues were greatest-hits collections. They were sometimes baited with one or two unreleased tracks to lure longtime fans, but their basic purpose was to collect an artist’s biggest hits and most popular live songs in one place so casual fans could hear what they most wanted in the most efficient way possible.

Streaming services such as Spotify have made that concept obsolete. If you can make a playlist of your favorite songs, why do you need the record company to do it for you? And yet the reissues keep coming, but now they serve a different purpose. Instead of emphasizing the most obvious tracks, these new packages rely on revelations from the vaults—unreleased, out-of-print or overlooked old releases.

At their best, these assemblages of old recordings became arguments about musical history. The curators of these projects are like lawyers in the court of public opinion, arguing that a certain artist, a certain movement or a certain phase of an artist’s career has been undervalued and overlooked. These curator-lawyers make their claims in the often-long liner notes and present as proof the tracks on the enclosed CDs or LPs. It’s up to us in the jury of music fanatics to hear the argument, examine the evidence and render the verdict. Here are some of the more compelling recent cases.

THE TITLE: The Beach Boys: Feel Flows: The Sunflower & Surf’s Up Sessions: 1969-1971 (Universal/Capitol/Brother)

THE ARGUMENT: One popular narrative about The Beach Boys is that their creative period ended when Brian Wilson had a nervous breakdown, gave up on his ambitious Smile album and released a truncated version of it as Smiley Smile in 1967. The counter-narrative points out that the group followed that last album with five inconsistent but often terrific records: Wild Honey, Friends, 20/20, Sunflower and Surf’s Up.

This new box set focuses on the latter two albums, arguing that these are crucial, underrated aspects of the band’s core achievement. The curators further argue that these releases mark the emergence of Brian’s brothers Carl and Dennis as important songwriters and producers who compensated for Brian’s decreasing participation.

THE BACKSTORY: Carl Wilson was only 15 when he sang on The Beach Boys’ “Surfer Girl” in 1962, and his brother Dennis, the only surfer in the family, was 17. Watching their older brother write ballads as beautiful as the modulating “Surfer Girl” and rockers as propulsive as “Surfin’ Safari” before he turned 20 couldn’t help but be intimidating.

But when Brian withdrew from full-time music-making after Wild Honey, his brothers had to fill the void. Carl sang lead on the two top-40 singles from that underrated, back-to-basics album, and largely co-produced the project with Brian. Dennis co-wrote and sang two songs on Friendsand two more on 20/20. Al Jardine, the band’s original folk music lover, sang his new arrangement of Leadbelly’s “Cotton Fields” on the latter. As a single, it flopped in America but was a top-five hit through much of the world.

This increased activity by the band’s other members set the stage for these two albums, where democratic participation and high quality intersected as never before and never after.

THE EVIDENCE: This five-CD box set includes the 22 tracks from the Sunflowerand Surf’s Up albums, plus 114 ancillary tracks from the same time period, 108 of them previously unreleased. The extra tracks are an assortment of live performances, non-album singles, abandoned songs, alternate takes, remixes, a cappella mixes and mixes without lead vocals.

A lot of this, admittedly, is excessive, of interest only to Beach Boys diehards. But a good chunk of it is revelatory, especially the songs that were never released in the ’70s and only existed on bootlegs till the band got serious about emptying the vaults. Some of those appear here for the first time, others in new, more presentable remixes. What’s crucial, however, is how all six members of the band—the three Wilson brothers, Al Jardine, Mike Love and Bruce Johnston—share the workload as composers, singers and producers as never before on both the official albums and the dozens of bonus tracks.

THE VERDICT: There’s a reason this collection is named Feel Flows. That was just one of two major songs (the other was “Long Promised Rose”) that Carl wrote for Surf’s Up. Just as Paul McCartney was the taskmaster and stabilizer during The Beatles’ Let It Be sessions, Carl filled the same role with The Beach Boys. Carl wasn’t the songwriting genius that his brother and McCartney were, but he was a gifted craftsman who got the best out of his bandmates. (And he would be crucial to helping Brian make the final Beach Boys masterpiece, The Beach Boys Love You in 1977.)

Dennis was especially prolific in this period, a rare phase of sobriety and stability for him. He co-wrote four songs for Sunflower, including the stirring ballad “Forever,” as well as 14 other songs in the box, laying the groundwork for his 1977 cult-favorite solo album, Pacific Ocean Blue. Not all of these lost songs are that great, but a few are—most notably the Brian-like “(Wouldn’t It Be Nice) To Live Again” and “Celebrate the News.”

Each of the albums in the box set’s title ends with a song rescued from Brian’s abandoned Smile project: “Cool, Cool Water” on Sunflower and the title track on Surf’s Up. These are two of Brian’s greatest songs, but so is “’Til I Die,” the mesmerizing meditation on mortality written several years after Smile. It appears on the box in four versions: the original album cut on Surf’s Up, a piano demo, an a cappella mix and an extended remix by engineer Stephen Desper that first emerged with a different lead vocal on the Endless Harmony Soundtrack. That version is one of The Beach Boys’ finest moments.

The two official albums aren’t as flawless as Pet Sounds or The Beach Boys Today, and Sunflower is more consistent than Surf’s Up, but they hold their own against anything else coming out in 1970-71.

Amid the surfeit of slightly different versions, the box does include some wonderful rarities in revealing new mixes: the rocking, blue-collar anthem “I Just Got My Pay” (written by Brian and Al, sung by Mike Love), the dizzying airplane song “Loop de Loop” (written by Brian, Al and Carl, sung by Al), the tropical fantasy “San Miguel” (written by Dennis, sung by Carl), the rock ’n’ soul “It’s a New Day” (written by Dennis, sung by Blondie Chaplin), and the finger-snapping swing of “Soulful Old Man Sunshine” (written by Brian, sung by Carl).

This box set could have done the job with just three discs, but it does make a convincing argument that the Beach Boys should be remembered for more than just their 1962-1964 surf-and-car hits and their 1965-1967 era of Beatles-esque chamber-pop. Their third phase, the 1968-1972 era of democratic music-making, yielded five standout albums, plus a bunch of delightful songs that they couldn’t fit on the official releases.

THE TITLES: Hasaan Ibn Ali: Metaphysics: The Lost Atlantic Album and Retrospect in Retirement of Delay: The Solo Recordings (Omnivore)

THE ARGUMENT: Hasaan Ibn Ali was more than just another talented jazz musician who was denied the discography he deserved. He was a groundbreaking giant whose technical mastery and harmonic innovations filled in the gaps in the development of the piano between Thelonious Monk, Andrew Hill and Cecil Taylor.

THE BACKSTORY: An older generation of Philadelphia musicians still speak of this jazz pianist with awe. His staunchest supporter, saxophonist Odean Pope, claims that Ibn Ali mentored John Coltrane in the early ’50s and instilled not only Trane’s unusual work ethic, but also his “sheets of sound” harmonies. Others on the scene, including McCoy Tyner and Philly Joe Jones, agreed that Ibn Ali had taken Monk’s innovations a step further.

When Max Roach heard the pianist, the legendary drummer recorded an album released in 1965 as The Max Roach Trio, Featuring the Legendary Hasaan. Atlantic Records was so impressed that they offered Ibn Ali his own recording date that same year, leading a quartet that featured Pope, bassist Art Davis and drummer Kalil Madi. Eight of the leader’s compositions were taped, and the album was ready to be mixed.

In the meantime, though, Ibn Ali had been imprisoned on a narcotics charge. Atlantic was unwilling to release an album by a performer who couldn’t support the project with live performances, and the tapes were shelved and presumably lost in a 1978 warehouse fire. That left only the one Roach album to substantiate the persistent claims that Ibn Ali was a forgotten jazz piano giant. That LP was impressive, but more evidence was needed.

THE EVIDENCE: It was only in 2017 that jazz historians Lewis Porter and Alan Sukoenig tracked down a duplicate copy of the tapes in the Warner Bros. library. The dub had seven of the original eight tunes and three outtakes. The duo released those 10 tracks as Metaphysics: The Lost Atlantic Album. And what a great loss it had been to let this music to go unheard from 1965 to 2021.

Porter and Sukoenig were so dazzled by the quality of that music that they investigated rumors of the solo-piano recordings Ibn Ali made at the University of Pennsylvania, and at various Philadelphia homes between 1962 and 1965. They came up with 21 tracks, mostly standards with a few originals sprinkled in, and they were also released this year as Retrospect in Retirement of Delay: The Solo Recordings. These make it obvious that Ibn Ali had great technical command of the keyboard—Art Tatum-like speed and Monk-like percussive effects

THE VERDICT: One often reads about this musician or that one who might have changed the course of jazz history if they’d just gotten the right break. When you hear the evidence, though, what you usually find is a very good, but less-than-transformational talent. But these two albums justify the hype about Ibn Ali. He does so much on these three discs: inventing single-note lines that snake through unexpected variations on a theme, even as he is whipping up thick storm clouds of percussive harmony.

Monk had leapt so far ahead in his conception of the jazz piano that most subsequent pianists were just trying to catch up with him. Ibn Ali was the rare exception who was able to pick up where Monk left off and take the next step. For that alone, this seemingly lost music is an invaluable discovery.

THE TITLE: Various Artists: It’s a Good, Good Feeling: The Latin Soul of Fania Records, The Singles (Craft Latino)

THE ARGUMENT: New York’s Fania Records was in some ways the Motown Records of Caribbean immigrants. It did not have the crossover pop hits that Motown enjoyed, but much like the Detroit label, Fania teamed young singers with seasoned jazz musicians and pop melodies with R&B dance grooves to create a bold new music in the ’60s. To the Motown formula, Fania added the three-against-two Caribbean rhythms of salsa for an unprecedented sound.

THE BACKSTORY: In 1964, Dominican-American salsa star Johnny Pacheco and Italian-American lawyer Jerry Masucci founded the label as a channel for Pacheco’s recordings. But when the bandleader switched from the traditional, string-backed charanga style to a new, horn-backed salsa, it marked a turning point in New York music. And when some younger singers added English lyrics and youthful pop hooks to the dance groove, the new boogaloo style was born.

The new approach caught fire among New York’s younger audiences and quickly attracted imitators. Fania moved smartly to corner the market on this new wave. There were hints of doo-wop in the vocal harmonies and of Latin jazz in the horn charts, but it was the direct emotional appeal of the lead vocals and the clave rhythms that cut through on the radio.

THE EVIDENCE: This four-CD, 87-track box set begins with early hits like singer Joe Bataan’s “Subway Joe” and trumpeter/bandleader Bobby Valentin’s “Use It Before You Lose It” (Junior Morales was the singer). Those tunes proved as infectious as the handclaps and chorus hooks woven into the production. Bataan signaled that he was fashioning a distinctly Latin spin on northern soul by putting a boogaloo spin on The Impressions’ “Gypsy Woman” and Smokey Robinson’s “It’s a Good Feeling.”

Conguero Ray Barretto was 38 and had six years of recording behind him when he released his first Fania disc in 1968. But the percussionist was a savvy musician and a youthful spirit, and he brought a sophistication to boogaloo hits like “A Deeper Shade of Soul,” with vocals by Pete Bonet. Monguito Santamaria, son of Mongo “Watermelon Man” Santamaria, fattened the bottom and added piano riffs to the Latin Soul sound. There were funny songs like Ali Baba’s “Ungawa” and lovely ballads like Ralph Robles’ “Maybe.”

As Bataan’s profile started to ebb, Fania found his successor in Ralfi Pagan, who was a soulful high-tenor singer on both the English and Spanish sides of his early LPs. When his salsa remake of Bread’s “Make It with You” became a crossover hit, he started emphasizing English. He tried to replicate that breakthrough with remakes of songs by Carole King and John Sebastian, but he never had another hit, though he continued to make splendid records. And just R&B moved toward the heavier grooves of funk as the ’60s turned into the ’70s, so did Latin Soul.

THE VERDICT: Fania never had the widespread commercial or cultural impact that Motown had, but that’s all the more reason to have our attention directed to these tracks, which radiated the youthful optimism and energy that so epitomized the ’60s. In addition to the music’s historic and cultural significance, traced in the box set’s 60-page, hardcover book, there’s the elemental sonic pleasure of the chorus hooks and dance grooves.

There was a lot more to Fania than the Latin Soul singles showcased here. The legendary salsero Willie Colon, for example, got his start at Fania, and Colon’s singer Ruben Blades became an international star for his stylish vocals and his social commentary songwriting. Legends such as salsa diva Celia Cruz and jazz pianist Eddie Palmieri also spent time at the label. But this anthology, by focusing on the R&B/salsa fusion singles, provides a useful service by spotlighting this great crossover moment that might have been.

THE TITLE: Neil Young & Crazy Horse: Way Down in the Rust Bucket (Reprise)

THE ARGUMENT: This recording from the Catalyst, an 800-person venue in Santa Cruz, California, purports to reveal a different side of Neil Young & Crazy Horse, allowing them to be more understated than their usual arena shows. The curators further claim that it captures Young on an especially good night on the guitar.

THE BACKSTORY: The ’80s are often described as a lost decade for Young—and not without reason. Feeling restless, he decided to explore some different musical genres that he’d always been interested in. Each album would be devoted to the sound of a particular genre, rather than Young’s usual roots-rock. There was a garage-rock record (Re-ac-tor), a techno record (Trans), a rockabilly record (Everybody’s Rockin’), a trad-country record (Old Ways), an L.A. pop-rock record (Landing on Water) and a horn-backed blues record (This Note’s for You).

Geffen Records, which released five of these albums, actually sued Young for not giving them typical “Neil Young” albums. These genre exercises were neither as bad as Geffen claimed nor as good as Young’s amazing early-’70s work. Young redeemed his ’80s work by reuniting with Crazy Horse for one very good album (Life) and one masterpiece (Freedom), followed by 1990’s very good Ragged Glory. Way Down in the Rust Bucket was recorded on Nov. 13, 1990, as preparation for the Ragged Glory tour.

THE EVIDENCE: The album’s 19 songs include eight from Ragged Glory, plus two songs from Re-ac-tor, three from Zuma and three from American Stars ’n Bars. The playing is appealingly relaxed, with Crazy Horse’s trademark looseness countered by just enough unified phrasing. And the guitar solos are terrific.

THE VERDICT: This is a thoroughly enjoyable outing by a great band, but it’s neither revelatory, nor transcendent. For that you have to turn to another Neil Young & Crazy Horse show at the Catalyst, back on Feb. 6, 1984, a show that has been often bootlegged, but never released officially. The band plays six songs from a studio album they were working on at the time. They sound so good that the album might have changed everyone’s perception of Young’s ’80s work. Alas, the album was never released; three of the songs were released in cleaned-up, less interesting versions on Landing on Water, and three were never released at all. That Catalyst show is the one that’s revelatory and transcendent.