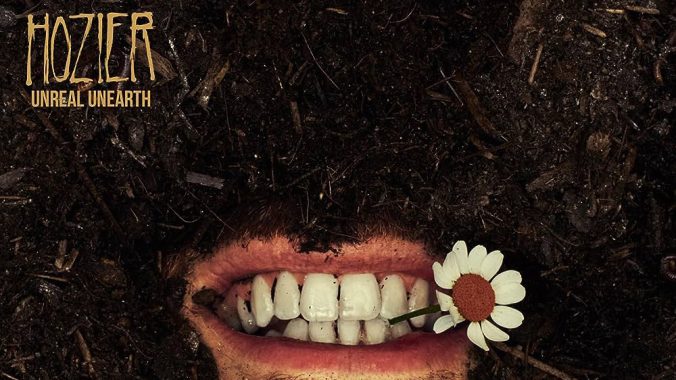

On Unreal Unearth, Hozier Makes His Boldest Work Yet

From Edgar Allen Poe and his poem “The Raven” to Vincent Van Gogh’s “The Starry Night,” some iconic artists are forever tied to their most famous work. For Poe, despite publishing over 70 poems, 68 short stories, a multitude of essays and a novel, “Quoth the Raven ‘Nevermore’” will be the line people remember when reflecting on his work. And while these two greats died well before the world celebrated their talent (Poe at 40 and Van Gogh at 37), most artists admit that being globally respected for one piece of work is better than none at all.

For Hozier, rightly or wrongly (mostly wrongly), his evolving discography will be endlessly measured against his juggernaut debut single “Take Me To Church” from 2013. Like a beacon of befuddling light that draws your attention away from the magnificent scenery upon which it sits, Hozier’s body of work has sat in the shadows of his most significant hit. Now, 10 years and two albums later, the Irish singer/songwriter returns for his boldest work yet, Unreal Unearth.

Hozier could sing Facebook’s Terms and Conditions and make them sound gorgeous. Sitting between Ben Howard and Father John Misty, his vocals are in the upper echelon of music, showing effortless anguish and soaring beauty with ease, showcasing complete mastery over his far-spanning range. While his sophomore record, Wasteland, Baby!, may have been too much of a pursuit to recreate past success, Unreal Unearth finds Hozier stepping fully into where he was made to be. The album is dazzling, multifaceted, patient at times and urgent at others—it will cast you out far and reel you back in just as fast.

We wade into the record with “De Selby (Part 1),” a hauntingly stripped-back tune complete with Gaelic lyrics and a string ensemble that foreshadows the aural aesthetics of the robust 16 tracks to follow. “De Selby” takes its name from a quirky, unseen philosopher portrayed in The Third Policeman novel published in the 60s, where he paradoxically examines human existence, a constant theme throughout Hozier’s own musings.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-