You want it darker? Is that a question or a dare? Perhaps it’s both. The titles of Leonard Cohen’s albums have always offered a pared-down glimpse into the essential nature of his work. Shaved and stripped of any unnecessary adornment, they have a tendency to be bleak, cold and often more than a little funny. Who but Cohen would have called the flawed portrait of an artist grappling with the failure of idealism and the disappointments of middle age I’m Your Man? Maybe the only thing that has saved Leonard Cohen from skating any nearer to the abyss has been his deadpan sense of humor. It’s an uncomfortable sense of humor to be sure, and the laughter Cohen’s work encourages often leaves a person with the feeling of having stifled a giggle in church.

Furthermore, Cohen’s album titles have often had the effect of minimizing not just his status as an iconic poet, but also the situations he describes in his work. If the titles of recent albums like Old Ideas and Popular Problems hinted at the fact that Cohen’s suffering is nothing special and that at best he’s just a finger pointing at the moon, with You Want It Darker he appears willing to enter the fray, deal with his audience’s expectations and lay things out as he sees them. No one really expects easy listening music when Leonard Cohen releases a record, but by saddling his new collection with such an ominous album title, you have to wonder whether he has “had it” and is simply taking the piss out of all of the suppositions that have been made about him over the years. You know, how almost everything he’s created this side of “Hallelujah” has been slotted under “poetry of despair” while the humor and gentle, forgiving humanity that is so central to his poetry and music has been almost entirely overlooked. How the deep, spacious resignation he’s cultivated allows for clear perception that has often been simply labeled as “depressing.” How much of Cohen’s audience has failed to understand that if you write about a razor blade, it doesn’t necessarily mean that you want to harm yourself.

The nine new songs that make up You Want It Darker explore very similar territory as he did on 1992’s The Future, but Cohen’s perspective appears to have shifted slightly since then. On that album, he predicted a future far worse than anything we could imagine, and sadly, events of the past two decades have shown him to be very prescient. “Anthem,” one of the songs on The Future, offered a counterpoint: “there is a crack in everything. That’s where the light gets in.” It’s hard to find those cracks on any of the songs on You Want It Darker. It’s not that Cohen is in an unusually depressed, sad or accusatory mood. There’s a much deeper sense of abandonment than what’s expressed in these songs. As he intones at the end of the title track, which castigates politicians and opportunists of all stripes who use religion to start wars instead of heal, “I’m Ready My Lord.”

The suggestion running through all of the songs on the album is that everybody should be getting ready for whatever fate is waiting for them. In that respect, You Want It Darker could be viewed as a summing up or an accounting of how an individual has lived his life. And, even though Leonard Cohen often uses levity and humor to offset the seriousness of his work, saying recently in print that, at best, he’s only ever “limped his way” through trying to live a spiritual life, his new songs are clearly no joke. In the same way that an old Zen priest is expected to leave a “death poem” for his followers to dissemble and at a certain point in life a Tibetan is expected to meditate on the Bardos (or stages of existence), Cohen appears to be in preparation for something—even if his threat to live to 120 proves to be true.

Making peace with the world and oneself is a theme that runs throughout You Want It Darker. Tracks like “Treaty,” “Leaving The Table,” “On The Level” and “Traveling Light” each examine the duties and pitfalls of mortal life. The narrator of each of the songs is as stripped naked before an unnamed power—that may be internal or external—as he weighs contributions in the light of damage done and how to reconcile the need for retribution with the power of forgiveness. As with all of Cohen’s later poetry, these new lyrics are pared down and polished, shaved and selected for their truth as much as their beauty. The songwriting is masterful, with some new compositions like “It’s Better That Way” in every way equal to the best work he has ever recorded.

Sounded like the truth/seemed a better way

Sounded like the truth/but it’s not the truth today

Better hold my tongue, better take my place

Lift this glass of blood/try to say the grace

If Cohen has been self-deprecatory about the way he sings in the past, there’s no room for teasing in any of his new performances. In truth, that’s because he doesn’t do a lot of singing on You Want It Darker, as he delivers his new lyrics as incantations rather than as melodies. And it’s true that the bare-bone rattle of Cohen’s voice is so intimate and vulnerable that at times it’s painful to listen to. Yet, like Dylan on an inspired night, it’s also worth noting that he’s also never demonstrated as much command as he does on all of these new recordings. For a guy with limited time at his disposal, Leonard Cohen doesn’t ever sound like he’s in a hurry. The phrasing is precise and blunt. Time hangs, and like the uncomfortable silence you feel when waiting too long for an old person to get up from a chair, the listener can feel a crackling in the air between notes and phrases.

Nothing is hurried. Each lyric and melody is direct, in the here and now. Nothing is arm’s length. At other times in his career, Cohen has sung to his audience as if from afar, with a slight removal as if he was a fly on the wall, a bird on a wire. The new songs have no distance, and the singer is not observing from any kind of tower—lonely, wooden or of song. They are too naked and spare, and leave nowhere to run. To experience this music properly requires a kind of surrender and a permission to immerse oneself fully.

If Cohen has occasionally suggested political solutions in his music, the solutions or approaches sung of on You Want It Darker are all solitary, internal and spiritual. Even if we’re all in the same boat together, what we do with what life has taught us is a private matter. There are no specific issues or campaigns being waged in any of Cohen’s new songs. The romantic, political and personal have all congealed into one. Pain is universal; its experience and expression are singular and absorbing. “You’ve got to walk that lonesome valley all by yourself,” as the old song goes. There is no solution offered other than surrender and the search for grace. It’s a state that Cohen realizes none of us sail immaculately into.

If thine is the glory/Then mine must be the shame

You want it darker/We kill the flame

It’s written in the scriptures/It’s not some idle claim

You want it darker/We kill the flame.

You can imagine Cohen shaking his head in disbelief as he delivers the lyric. Whoever the “you” is directed at in “You Want It Darker,” can’t possibly imagine what they’re asking for.

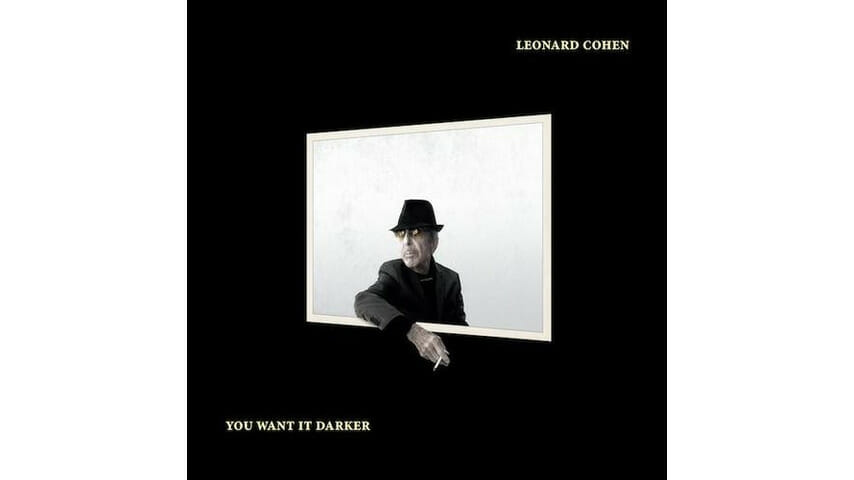

Adam Cohen, Leonard’s son, was brought on to produce You Want It Darker after the singer was sidelined by back pain earlier in the year. It turned out to be a smart move that allowed the record to be completed as comfortably as possible without a time frame. More than that, Adam Cohen obviously thought a lot about how to capture his father’s lyrics in song, and has produced the warmest sounding music that Leonard Cohen has offered since Recent Songs came out in 1979. The natural acoustic sounds that grace the songs offer the perfect counterpoint to Cohen senior’s bare lyrics and intonation. His battered old Cassio synthesizer, long the subject of onstage jokes and the dominant sound in his later recordings, has gone by the wayside. In its place are intricate string sections and the reverberating sound of a real bass. Musically, the songs embody the lovely old-world aesthetics of his touring band—a sound that has elevated and unified all of his output when presented in concert. The presence of a gypsy violin tells the listener that the stories we are hearing are as old as time, and it’s easy to imagine the songs being shared around a campfire near a caravan in the woods.

One of the most discussed features of You Want It Darker is that, in many cases, the female backing singers who have long been a feature in Cohen’s music have been replaced by male voices, provided by Montreal’s Shaar Hasomayim Synagogue Choir. It’s a small but significant change that almost completely alters the intimacy of what Cohen sings of. It’s as if the women, the sisters of mercy who have always been healing figures who offer protection, have flown the coop. The presence of the cantor singers suggests that ultimately there are no arms to lie in and no safe haven. Their male voices suggest a shift from outer to inner concerns and intensify the sense of going deep within where there is no distraction and no one to commend or blame but oneself. It’s a subtle difference, to be sure, but is one of many instances in which Adam Cohen as the producer suggests the profound within his father’s work without any unnecessary flashes or undue attention.

Leonard Cohen’s fans have been spoiled with a wealth of very good new material in the last decade, so it’s become easy to take his continued ability to produce a seemingly endless stream of songs for granted. For, as understated as they were, his last two albums, Old Ideas and Popular Problems, were very solid additions to his discography. Whatever they lacked in the way of musical innovation, they were still as good as many of Cohen’s recordings from the past. You Want It Darker is better than either of those records, and may contain the best music he has created since Various Positions came out in 1984.

Much has been written recently about how Leonard Cohen is putting his house in order and that he’s said he’s “ready to die.” There are, of course, many ironies implied by this: If a part of dying is letting go, Cohen has certainly given his fans a lot to hold onto in the past few years. Or, that well past the age of respectable retirement when one could be expected to withdraw from worldly things, he toured and recorded more than at any other time in his life. There might be a lesson or a punchline in this somewhere, but one thing’s for certain: for a Zen minimalist, Leonard Cohen is leaving a hell of a big vapor trail.