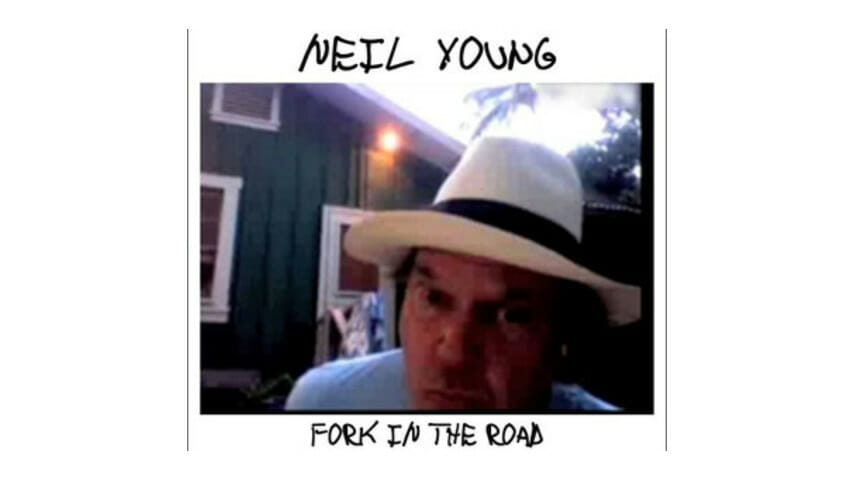

Road warrior still making driving rock

The backstory on Neil Young’s umpteenth studio album—rock star works with crazed mechanical genius to convert a beat-up ‘59 Lincoln Continental into a lean, green, eco-friendly machine, then drives it across America just to show that he can—informs nearly every song on Fork in the Road. There are almost as many references to cars, wheels, and roads in these lyrics as in the entire Springsteen catalog.

Not surprisingly, all the car references and metaphors mean more than they seem, and Young has more on his mind than simple nostalgia for the golden age of the American auto. Like 2006’s caustic Living with War, Fork in the Road finds Neil in cub-reporter mode, dashing off hastily scrawled dispatches that serve as his State of the Union address, circa the desperate economic spring of 2009. The sloppily played garage rock riffs complement the slapdash nature of the lyrics, and—as you might expect—it’s that loose, under-rehearsed and under-written methodology that is both the album’s strength and its downfall.

There are no winding godfather-of-grunge solos here, and no hippie poetry. There’s only Young, living and rocking in the moment, for better or worse; a pattern he’s followed since the 2005 brain aneurysm that almost killed him. Maybe when you believe you don’t have much more time you don’t labor over the results.

Still, there are some jaw-dropping moments—and not because of the musical majesty, either. Did Young actually write a saccharine ballad based on that horridly clichéd slogan that it’s better to light a candle than to curse the darkness? Oh God, yes he did. Did he steal the riff from Van Morrison’s “G-L-O-R-I-A” for one track, a riff so familiar and so overused that most third-rate bar bands know better than to touch it? Yes, he did that, too. But for every head-scratcher, Young churns out a sturdy, perfectly serviceable garage rocker that succeeds because of the passion and conviction he brings to the proceedings. “Just singing a song won’t change the world,” he opines on one song, but, unreconstructed hippie that he is, he doesn’t really believe it. He’s all about changing the world—through song, through being an ornery prophet and social critic, through driving a dilapidated car and showing that it’s possible to get a hundred miles per gallon. It’s hard to do anything but wish him well. There are half a dozen tracks here, most notably the scalding “When Worlds Collide,” the darkly pensive “Off the Road,” and the scathing title track, where it is impossible to separate the primal roots rocker from the social activist. And that’s when he’s at his best.

Near the end of the title track, an otherwise blistering attack on Wall Street bankers and bean counters without souls, Neil stops to pen a love letter to his fans: “Big rock star, my sales have tanked / I still got you. Thanks.” Like the rickety jalopy he drives, there is much more under the hood than meets the eye. Long may he run.