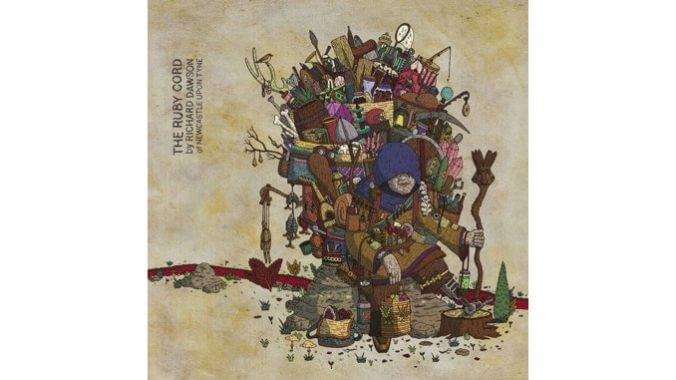

Richard Dawson Threads Patience and Empathy on The Ruby Cord

The Newcastle Upon Tyne avant-folk songwriter delivers his most ambitious compositions to date in this conclusion to a trilogy of time-specific concept albums

Music Reviews Richard Dawson

In the earliest months of 2020, Richard Dawson and his partner Sally Pilkington started a new project called Bulbils, a means of reconfiguring how the two approached music and offered it to fans. Shirking the refinement and long production cycles of traditional release models, the duo set about with a simple aim: record whatever was on their minds any given day and upload it as it was, without further tweaking. The result was something akin to a communal salve—mental relief from nascent pandemic worries performers and listeners might have been facing in their own lives—oft-delivered via meditative ambient textures of guitars, vocals, synths, and anything else Dawson and Pilkington might have felt the urge to use in the moment.

Bulbils arrived shortly after Dawson’s prophetically titled 2020, his last solo studio album, and its immediate effect on his follow-up is palpable. The Ruby Cord marks both a culmination of and departure from the avant-folk style Dawson broke out with on 2017’s Peasant. Dawson’s compositions have always relished in eccentricities and sheltering hidden nooks just beneath the surface, be it in “Ogre” withholding its refrain until its climax or the hairpin turn into an Iron Maiden-esque riff on Circle collab track “Methuselah.” But The Ruby Cord sees the songwriter reaching for a profound patience heretofore unseen in his work, pairing a thoughtful variation on the unfurling ambient work of Bulbils with the empathetic storytelling of Peasant and 2020.

The shift is starkly apparent on The Ruby Cord’s very first song, “The Hermit.” At a whopping 41 minutes, it’s Dawson’s longest track to date—an entire album in miniature. Over 11 minutes pass without any words, filled with variations on the same shambling guitar lick, gentle brushes of percussion, withdrawn piano and harp, and stray wisps of strings. When Dawson’s voice finally comes in, it’s as if the track itself is in the midst of adjusting (his first lyrics: “I’m awake but I can’t yet see”), before nestling into the instrumental’s unhurried pace and long, winding narrative. At points, the instruments disappear completely, leaving Dawson’s words ringing out alone, impossible to ignore. It’s a striking introduction to The Ruby Cord, and one that indelibly sets the tone for the rest of the record.

Much of the album operates in this relatively subdued mode that complements Dawson’s strengths as a folk singer, from the gentle strums that carry “Thicker Than Water” to the spare harp accompaniment from Rhodri Davies that forms the core of “Museum.” When hewing closer to the delicate, Dawson imbues the record with gorgeous displays of his idiosyncratic voice, often projecting and stretching syllables far past where a traditional folk singer may have, reaching to the upper limits of his falsetto to fill songs’ negative space. “The Tip of an Arrow” becomes one of the finest displays of his presence as a vocalist for this reason: Dawson’s warble rises and falls with the cadences of his narrator’s gratitude at being able to raise a daughter in the wake of other children’s premature deaths. At its best, The Ruby Cord is able to convey as much story via the timbre of Dawson’s voice as it does through his verbose lyricism.

Dawson brings no shortage of compelling narratives to this record, continuing Peasant and 2020’s propensity for song-length vignettes that thematically snap together when put in sequence. What’s especially noteworthy this time around is how naturally Dawson’s writing about a speculative future fits with his descriptions of Anglo-Saxon England on Peasant, or the dystopian realities of the present day on 2020. A listener may not even pick up on the few tipoffs marking The Ruby Cord as a record set 500 years in the future on first listen. (A knight, seemingly far-flung from the past, factors prominently into the conclusion of “The Hermit.”) But the hinted-at futuristic elements—the unaging narrator of “The Tip of an Arrow,” or the virtual reality screens concealing loved ones’ corpses on “Thicker Than Water”—ground Dawson’s stories, selectively implemented to add emotional complications, rather than alienate listeners. It’s no coincidence that Dawson, in interviews, chose to draw parallels between this album and a quote from Ursula K. Le Guin about commodified fantasies, and how we cling to them as much as we do stories of old.

However, The Ruby Cord isn’t just a muted means of Dawson conveying this theme. Though “The Hermit” is one of the most understated works of the songwriter’s career, the record often plays with its dynamics as each track sees fit. “The Tip of an Arrow” occasionally breaks into hard-rock gallops when its action picks up. Closer “Horse & Rider” sends the record out with a soaring big-band swell, even as its lyrics culminate on a “neverending passage through the cold and dark.” And right as the album seems to be settling into relative quiet, highlight “The Fool” barges through the tranquil tracklist, skewing more Oingo Boingo than Joanna Newsom in its strung-out, new wave-influenced freak-folk.

The shrewdest of these shifts in sound comes at the end of “Museum,” a song about an exhibit charting the breadth of human existence following humankind’s extinction. Listing off common human experiences ranging from the mundane (“A classroom deep in thought”) to the unjust (“Riot police beating climate protestors”), Dawson chooses to end on “Babies being born.” Melodic vocalizations follow before the track builds from minimalist harp to a booming coda of percussion and synth. Here, Dawson seems to be arguing, the failings of humankind are not enough to negate the sheer miracle of our existence.

This sentiment itself is an echo of the closing stretch of “The Hermit.” A chorus of voices circles a refrain—subdued, like a reverent murmur—for 14 minutes: “Tiny cobles out at sea / A black wall of cloud to the east / And a taper of rainbow / Faintly aglow / Amidst their wakes.” Like much of Dawson’s songwriting, it’s an ending that finds hope in the darkest shrouds. Each repetition further elucidates the hopeful outlook of its concluding lines—the promise in that faint glow that can weather even the grimmest futures.

Natalie Marlin is a freelance music and film writer based in Minneapolis who has contributed to sites such as Stereogum, Little White Lies and Bitch Media, and previously wrote as a staff writer at Allston Pudding. She also regularly appears on the Indieheads Podcast. Follow her on Twitter at @NataliesNotInIt.