Austin, Texas: Music from the South and Southwest

Road Music, Chapter Five

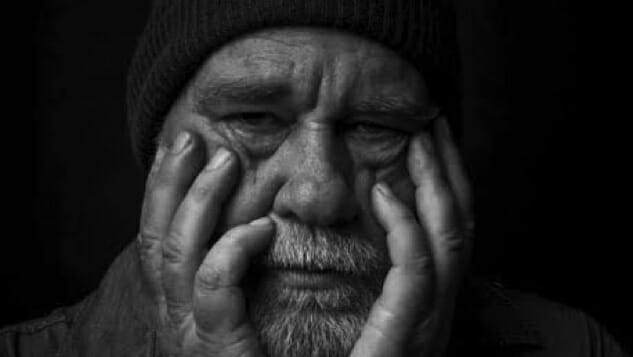

Jon Dee Graham photo courtesy of the artist

South by Southwest takes its name from its original mission: to showcase musicians from the American South and Southwest—two regions that overlap in Central Texas. In the conference’s early years, that emphasis was obvious. Performers from along the Gulf Coast and the Rio Grande and Colorado Rivers presented regional music for regional audiences. You could come from East Coast or the West and feel as if you were eavesdropping on an ongoing conversation.

By the turn of the century, however, that mission had faded. A film festival was added, then a technology conference and a comedy festival. The big money wanted to turn SXSW into a place where they could present and discover acts from anywhere. Before long, SXSW often felt like an indie-rock festival in Brooklyn or a world-music showcase in Berlin. There were still regional acts sprinkled throughout the schedule, but they didn’t always play regional music and they often got eclipsed in the competition for attention.

The original mission persisted, though, in the ancillary events during SXSW week. With a little effort, one could still sniff out local performers and local audiences—the two main reasons for traveling to Texas to hear music. You could find it at day parties that take over patios, back yards, office buildings and bars all over Austin. You could find it in the satellite festivals out in the hills. And you could occasionally hear it in the official SXSW showcases.

Bloodshot Records, for example, took both the official and unofficial routes. The Chicago label with several Gulf Coast acts hosted six of its acts at an official showcase one night and nine of its acts at it annual Friday afternoon party at the Yard Dog, Texas’s leading outsider-art gallery.

Under a white, canvas tent in the gallery’s backyard, the Dallas band the Vandoliers presented their crazy idea of mashing together punk-rock and mariachi music. Here was regional music at its most inspired: taking an old tradition and giving it a hard twist. On most songs, the rhythm section cranked up fast, hard garage-rock, but then trumpeter Cory Graves and violinist Travis Curry would add a cheerful Mexican motif, changing everything.

The mariachi music brightened up the rock ’n’ roll, and the rock ’n’ roll roughened up the mariachi. This enabled lead singer and chief songwriter Joshua Fleming to work the optimistic and pessimistic sides of his outlook with equal appeal. When the Vandoliers dropped the mariachi influence for a song or two, they were much less interesting. Rather than worry about this mash-up becoming repetitive, they would be smart to seek new ways to mix the two elements.

The afternoon’s highlight was Gulf Coast legend Linda Gail Lewis, a Louisiana shouter and boogie-woogie pianist nearly as impressive as her big brother Jerry Lee. She’s made records in the past with Jerry Lee, Stephen Ackles and Van Morrison, but her most fruitful collaboration has been last year’s Wild! Wild! Wild! album with Robbie Fulks. Fulks wrote her some smart, catchy and witty songs, and framed her voice and piano with a top-drawer rockabilly band.

As good as that album was, this show was even better. Fulks’ Texas band includes Merle Haggard guitarist Redd Volkaert and Willie Nelson bassist Kevin Smith, joined by drummer Chris Gilson and pedal steel guitarist Tommy Detamore. All six musicians seemed more comfortable with the material and each other than they had in the studio. They sounded both more relaxed and more exciting, especially on the set’s climax: Jerry Lee’s “Great Balls of Fire.”

Lewis and Fulks added two other Jerry Lee tunes (“High School Confidential” and “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Going On”) and the gospel hymn “I Am a Pilgrim” at Saturday afternoon’s annual Mojo’s Mayhem, hosted by singer and radio DJ Mojo Nixon. The highlight of this party was Austin’s own Jon Dee Graham & the Fighting Cocks, who were warming up the Continental Club for their official showcase later that night. “Welcome to Austin,” Graham greeted the shoulder-to-shoulder crowd, “where we pave the streets with shattered dreams.”

Graham’s own dreams have paved a stretch of South Congress Avenue, and in the glitter of that surface, one can glimpse some of the best songs to come out of Texas in this century. If this were a just world, those songs would be on the radio rather than underneath Austin’s ever-worsening traffic, but it’s not a just world, and that’s the subject of many of those songs.

Is there a better song about the cost of drugs and alcohol than “Beautifully Broken”? From the three jangly, descending chords that pull you into the song from the intro to the description of a rehab center “for the drunk and the disturbed, for the drugglers and the strugglers, God’s crippled little birds,” everything leads us to the saddest, bravest chorus ever written. It strips away the last scraps of romanticism from getting high: “Not beautifully broken, just broken, that’s all.” It was the best song I heard on any subject all week. Except, perhaps, “Copper Canteen,” which James McMurtry sang in the subsequent set.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-