Internet Vote Swapping: What Is It, and Can It Actually Work?

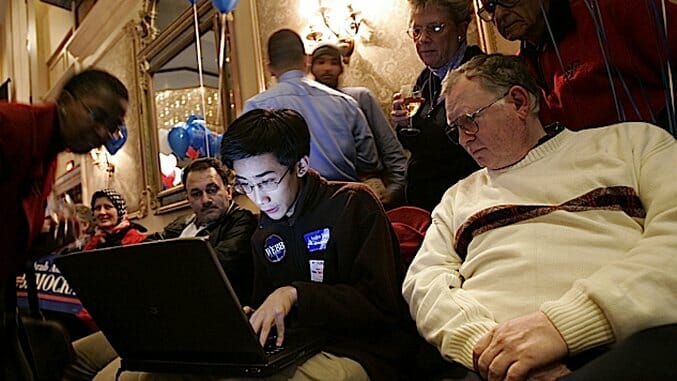

Photo by Alex Wong/Getty

For many establishment Republicans, the 2016 presidential election has provoked something of an identity crisis: After Donald Trump earned more GOP primary votes than any other candidate in history, it became clear that Reagan Republicans are now outnumbered by those rallying behind a television celebrity with a dubious business and personal history. That left the likes of the Bushes, Mitt Romney and others standing on the fringes asking what they are supposed to do—support the Republican nominee, reluctantly vote for Hillary Clinton or go with one of the third-party non-contenders

Or is there a fourth option for those on the #NeverTrump train? This year, some voters are strategically swapping their votes in ways that allow them to follow their conscience while still blocking Trump’s potential path to victory.

It was a concept that controversially rose to semi-prominence with “Nader Traders” during the 2000 election to block George W. Bush. In that age of the early Internet, the vote trading efforts were hastily organized and heavily resisted; the main site shuttered before the election after threats from then-California Secretary of State Bill Jones. As we know, Bush went on to win the presidency when the election went to the courts.

Although it was too little, too late to affect the outcome of that election, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the National Voting Rights Institute took up the cause by arguing that vote trading is protected by the First Amendment. In 2007, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals agreed Internet-based vote swapping is legal. As Judge Raymond C. Fisher said in the official opinion, “The websites’ vote-swapping mechanisms as well as the communication and vote swaps they enabled were constitutionally protected.”

In the two presidential elections since then, vote trading hasn’t made many waves. But this election is different. With both Clinton and Trump topping 50 percent in the averages of their latest unfavorability polls, it’s evident a significant portion of the population isn’t thrilled about the options put forth by the two major parties. For those who are wholeheartedly against Trump, but also want to represent their opinion that the United States’ two-party system isn’t working, that puts them in a difficult position: Protest vote for Jill Stein, Gary Johnson or some other relative unknown and risk inadvertently helping Trump—or reluctantly vote for Clinton.

Complemented by the rise of social media and Internet platforms, that’s where vote trading comes back into play.

“As Republicans voting for Clinton, we had something of a journey to get to ‘country before party,’” says John Stubbs of his and Ricardo Reyes’ path to co-founding Trump Traders. That poses a particularly big dilemma for third-party voters in swing states. “If you for for anyone other than Clinton or Trump, you are letting someone else decide the election. Maybe you think Clinton is a two, but Trump is a negative 11, and there is a difference.”

Seeking to provide options for people who want their protest votes to be heard while barring Trump from the Oval Office, Stubbs and Reyes launched Trump Traders, which runs through Facebook by pairing a voter from a swing state and a voter from a safe state. Within the past few weeks, Stubbs says they’ve connected 12,000 participants, with more than half of those voters signing on since last Friday.