Winning Time: The Rise of the Lakers Dynasty Is a Flashy, Raunchy, Star-Studded Spectacle

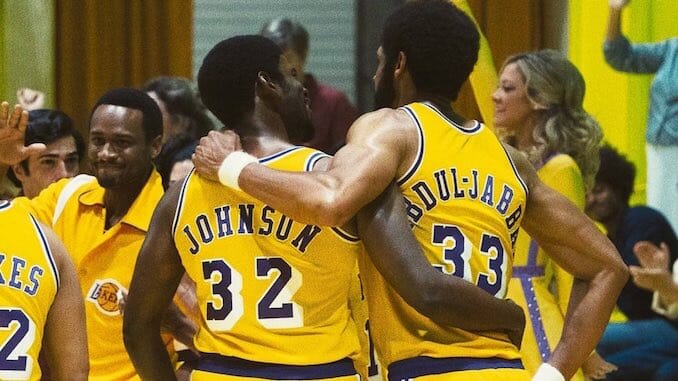

Photo Courtesy of HBO TV Reviews Winning Time

Forget the stacked all-star cast. Forget the comedic pedigree behind the camera. Forget, even, the splashy decade of complete Lakers dominance that inspired the show in the first place. The thing that will strike you hardest when you tune in to the first episode of Winning Time: The Rise of the Lakers Dynasty, which debuts on HBO this coming Sunday, is that television? It’s a visual medium.

Okay, so, that may not sound like the wild revelation I set it up to be. I mean, of course television is a visual medium! It’s literally right there in the name! But for all that the narrative integrity of every film and television project produced since the Lumière brothers first screened La Sortie de l’usine Lumière à Lyon has hinged (at least in theory) on the visual elements afforded by the invention of the moving picture, it’s nevertheless rare for a television show to appear that doesn’t just “hinge” on the interplay of lighting, costuming, shot composition, editing, film texture, etc., but genuinely suffers from the viewer glancing away from that interplay for even a second.

And that, from its very first scene—a series of extreme, period-accurate close-ups of people sitting in the waiting room of a busy doctor’s office at Cedars-Sinai on November 5, 1991—is what Winning Time does. It’s not just the deeply ‘90s U.S. News & World Report cover story on the crisis in the Middle East (“Saddam Hussein: The Real Target?”) that director/Executive Producer Adam McKay wants you to take note of as he sets the scene, nor the blocky gray Gameboy fitted with an NBA All-Star Challenge cartridge being played by a red-headed tween clad in an oversized bright purple and gold Lakers jersey. It’s not the tiny CRT waiting room TV airing an interview with an astonishingly young Brooke Shields. It’s not even the low-level hum of digital beepers and landline telephones ringing in the background as these mini tableaux start to add up to something significant.

No, it’s the quality of the film itself. The texture. All those little bits of set dressing I listed above, they’re critical, sure. But what stands out most about them—truly, what all but slaps you in the face—is the fact that they look like they were literally filmed in 1991: soft edges, slightly desaturated colors, flat lighting, the lot. You could turn around and splice that entire waiting room scene into an episode of Doogie Howser, M.D., and no one would be the wiser. Same, too, the more documentary-style handheld close-ups that take over once the scene shifts to a tan-suited Magic Johnson (Quincy Isaiah), nervously wringing his hands in an exam room while waiting for his ride to pull up out back, away from the paparazzi. Honestly, if you didn’t know any better, you could easily be tricked into thinking you’re getting a sneak peek at the real Magic Johnson docuseries. set to come out on Apple TV+ next month. (That Isaiah, a relative newcomer in Hollywood, looks uncannily like the real Johnson, certainly doesn’t help.)

While the action immediately following the series’ unskippable title sequence flings the story back to 1979, this assiduous adherence to period-accurate texture remains. For all the time we spend in the Lakers 1979-1980 season in Winning Time’s first eight episodes (provided to critics for review, out of an eventual ten), this means more graininess, a warm golden tint across everything, and flashes of natural light that wash out whatever it is we’re supposed to be looking at as often as it illuminates it. Moreover, just like in that 1991 opening scene, the types of period-accurate shots that showrunner Max Borenstein, cinematographers Todd Banhazl and Mihai Malaimare Jr., and the series’ small stable of directors use constantly shift between “1979 TV show” (think: Charlie’s Angels) “1979 archival footage” (think: Lakers at Celtics, 1980) and “1979 hand-held documentary footage” (think: every home video parents shot of their Xennial kids). And when I say these textures are constantly shifting, I don’t just mean from one scene to the next, or even from one shot to the next. More often than not, the textures will shift multiple times within the same frame.

Taken altogether, this approach to telling the story of the Lakers’ meteoric rise is deeply fascinating. It also makes it nearly impossible to get the full Winning Time experience if your eyeballs aren’t glued to the screen 100% of the time. And that’s without me even mentioning the microsecond flashes of pop culture moments, fictional memories, news clips and reaction shots that are squeezed in throughout, or the occasional explanatory text that gets slapped on the screen whenever a surprisingly famous character (say, Paula Abdul) or shocking historical detail (say, Nike’s stock valuation thirty years after Phil Knight first met with Magic) is at risk of not being clocked by the audience, or, even, the raw magnetism of each member of the story’s sprawling cast. But that’s exactly the point: it’s a critically rich visual text!

Of course, visual maximalism is, at this point, something of a calling card for HBO. As my fellow Paste TV contributors are well aware, one of my favorite things to rant about is the fact that, much as HBO superfans might act otherwise, Euphoria didn’t invent the teen soap wheel, nor Westworld the sci-fi western one, nor Game of Thrones that of the epic fantasy. (What did they invent? Genre storytelling with massive budgets.) But even I can’t argue that they haven’t all left an aesthetic mark on popular culture. Similarly, while Winning Time hasn’t invented the sports docudrama, I can’t see a future in which it doesn’t set a visual standard by which all sports docudramas (at least in the near term) will be compared.

At this point, I realize we’re nearly a thousand words into this review and I have yet to discuss in any real detail A) the cast, B) the story (and the historical accuracy thereof), or C) the basketball. Apologies. But also, I have a good reason: It’s hard!

In the case of the first, the Winning Time cast is enormous. At the Winter TCA panel for the event late last month, the series’ Zoom grid measured an unprecedented 3×5. There were so many cast members present, I’m pretty sure Jason Segel, Jason Clarke, and Tamera Tomakili didn’t even get a chance to speak. And that panel represented barely a fraction of the talent that walks through Winning Time’s first season at one point or another. To go into even minor detail about the work any of them are doing would take another thousand words. But what I will say is this: John C. Reilly, for all that the character he plays (Lakers owner Jerry Buss), is big and brash and louder than life, is doing some of the most nuanced work I’ve seen from him. Solomon Hughes, as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, so masterfully exudes Kareem’s iconic (and semi-threatening) stoicism that it would seem like too much to ask that he also have mastered his infamous hook shot—and yet! And as a rookie Earvin Johnson, Quincy Isaiah, beyond showing enough skill on the court to be believable as a young star, has enough charisma to knock you to the moon.

In terms of the second, well, the story is the history. And in terms of historical accuracy, man, I will just say this: No injunctions against spoiling an audience on a show’s major plot points have ever sent me into as wild an existential spiral as those attached to each of these eight screeners managed. For example, I don’t think it could be considered spoiling things to note that by the late 1970s, the Lakers were a middling franchise in a middling league whose prospects needed the arrival of Jerry Buss and his singular vision (slash, money)—and of course Magic Johnson, Jack McKinney, Paul Westhead and Pat Riley—to shoot the opposite direction. Those aren’t spoilers; that’s Wikipedia. Similarly easy to find on Wikipedia: The fact that the Lakers beat Boston in both of their meetups in the 1979-80 season. But what about the [redacted] that changed the team’s coaching direction just week’s before training camp? Or the [redacted] that changed the coaching direction again mid-season? I mean, Googling any one of the characters is likely to spoil you more than I possibly could.

What that means, then, is what I shouldn’t spoil you on is the how. Not just the global how of what details Borenstein, McKay, and writer/EP Rodney Barnes have picked to tell the story of Jerry Buss and the Lakers, but how they’ve molded those details just enough to make a piece of truly arresting television. And man, while the placard at the start of each episode does warn viewers that “some of the events and characters have been fictionalized, modified and composited for dramatic purposes,” I’m not sure even that will be enough to prepare some Lakers (or Celtics/NBA/LA) superfans for some of the wilder swings they’ve taken doing said “fictionalizing, modifying and compositing” real game-time facts.

Honestly, the thing that most helped me overcome the cognitive dissonance even I, a non-superfan, felt when realizing how big they went in some key details, was to start thinking about the show as a basketball-centric cousin to For All Mankind. Which is to say, as a delightfully rich (if slightly more raunchy) alternative history. Approaching the story this way will make it easier to separate your enjoyment of how various real people are being portrayed from any possible discomfort you might feel over how those same real people might feel about the portrayal. Which is, in itself, not nothing!

As for the final point—the basketball—all I can say is, it looks good. What skills Isaiah, Hughes, DeVaugh Nixon (here playing his own father, Norm Nixon), Delante Desouza (Michael Cooper), Wood Harris (Spencer Haywood) and Sean Patrick Small (Larry Bird) bring the the court are convincing enough that the camera can stay on them for long shots from multiple angles, and whenever trick shots or buzzer beaters need to be fit in, well, the editors are on hand to save the day.

Ultimately, if I have any reservations about the ultimate success of this series, it’s in how it will manage to resolve the tension between its ambition and its length. Despite the Showtime era running through the entirety of the ‘80s, the first seven episodes of the series take place in 1979. That leaves a lot of ground to cover in the final three episodes! But if the creative confidence shown by the whole Winning Time in the first seventy percent of the season is anything to go by, they will pull it out in the end. And I will be cheering them along the whole way.

Winning Time premieres Sunday, March 6 on HBO at 9pm ET, with episodes streaming on HBO Max the next day.

Alexis Gunderson is a TV critic and audiobibliophile. She can be found @AlexisKG.

For all the latest TV news, reviews, lists and features, follow @Paste_TV.