Serial Experiments Lain: Peeling Back Layers of Queerness Through Y2K Technology

Photo Courtesy of TV Tokyo

Animation, unlike traditional forms of film or TV, allows for complete abstraction. Even in popular anime, like Dragon Ball Z and Sailor Moon, time contorts around long power-up sequences and dramatic, fast-talking banter in the heat of battle. A friend of mine affectionately refers to this phenomenon as “Jojo Time” in reference to Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure,, which famously portrayed a final battle that took place over just a few minutes in a 4-part finale.

As you stray further into the world of anime, you’ll find more short-form, experimental series that are not meant for a wide audience. Directors such as Masaaki Yuasa, Kunihiko Ikuhara and Satoshi Kon are well-known for their experimentations with the medium with keen interests in portraying human experience through conceptual means. Many of these series were inaccessible outside of importing and dedicated fan communities up until the early 2000s. While, to a degree, the anime craze had caught on outside of Japan, only a select few shows aired on Western networks and even fewer were available on VHS.

Around the time of the internet’s inception, groups known as fansubbers began making and distributing bootleg tapes with their own translations. Later, these versions would be uploaded online—given the amount of times these versions would be ripped and pasted from tapes, much of the original fidelity was lost, and fansubbers were often amateur diehards who wanted to share something they were passionate about. It was a thankless undertaking, but many—like myself—were mystified by the inaccessible nature many of these shows took on. Though unintentional, it only serves to heighten the mystique of shows like Neon Genesis Evangelion and Revolutionary Girl Utena. These fansub legacies still follow them to this day.

Growing up during the advent of streaming, I found myself in these anime I couldn’t understand, in the feelings of these protagonists whose emotions swirled and shifted. Often, emotions were solely communicated through surreal flourishes of rose petals, darkening, grotesque facial expressions, and acts of affirming violence. Sometimes these protagonists hurt themselves. These shows had a subconscious effect on my queer identity, whether positive or not, and continue to mean a lot to LGBT viewers because of their non-representational forms of storytelling. Today, I’d like to look at one such example, Yasuyuki Ueda’s Serial Experiments Lain, which not only mirrors my experience growing up as a queer kid but as a person who came of age during the digital revolution.

![]()

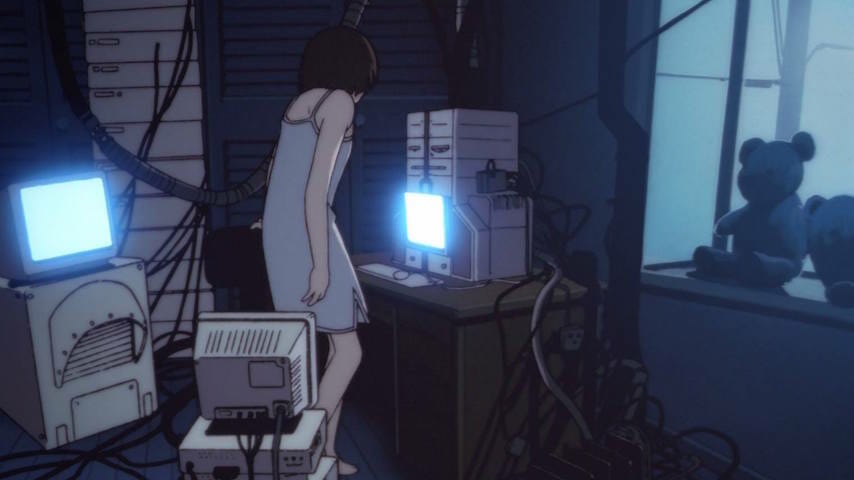

LAYER 01: W[E]IRD

Alone in her room, Lain Iwakura stares at the vacuous blackness of her computer monitor. At home, I sit cross-legged at our family computer, situated so it is facing my dad’s work computer against the opposite wall, leaning in as Lain activates her e-mail for the first time. The quality of the video is poor—I’m watching Serial Experiments Lain for the first time on a bootleg website on terrible broadband, the only option available in my rural, South Georgia hometown to this day.

Technology has always had a queer history. Many teens who reached adolescence in the aughts, like myself, turned to cyberspaces as a mother-hub for communities, niche hobbies, and escapism. During this time, while internet users were still developing a global language, children and teens were easily exploited by other alienated people who crept to the farthest reaches of the web as a haven. There were many times when I nonchalantly shared my age and name with self-identified adults—adults who I would IM daily and form invisible bonds with. We never shared photos of ourselves and, as time went on, we would all begin using fake names, something later referred to as a “display name” or an online “handle.”

Lain’s first encounter with someone online wasn’t a stranger. Instead, it was a message from a dead classmate who committed suicide just days before their correspondence. Several of Lain’s peers received the same message, but Lain was the only one to approach it coldly, without panic—with almost dissociative precision. Soon we see her having multiple conversations with many people at once. Their conversations are intense and intimate, but Lain remains coolly detached. They trade secrets but also transfer emotional baggage—these become inextricable from one another.

In his book Simulacra and Simulation, post-structuralist Jean Baudrillard describes simulations as “a real without origin or reality” or a “hyperreal.” In the Wired, a heightened version of the internet that serves as a virtual reality, Lain can experiment in a non-referential world, a playground untethered from the material, emotionally downplayed offline world. Her personality can warp to the point of hyperbole, and exist as many different selves to different people—to the point that her parallel personalities are pointed out as “total opposites.”