Netflix’s Heist Episodes on “Pappygate” Are a Tale of Cartoonish Bourbon Incompetence

Photos via Netflix, Buffalo Trace, via Unsplash (Josh Collesano) TV Features whiskey

If you’re a bourbon fan, you’re no doubt familiar with the story of “Pappygate,” the theft of hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of Pappy Van Winkle bourbon (and tons of other whiskey) from the Buffalo Trace and Wild Turkey distilleries in Kentucky. The story broke big back in 2013, becoming national news when morning shows and newspapers couldn’t resist the romantic, bootlegger-esque sound of it—how does one make off with cases upon cases, and indeed entire barrels of whiskey?

The case, and the eventual arrests that followed, have been bourbon industry legend ever since, but now a wider world will likely hear about “Pappygate” for the first time via Netflix’s new crime docu-series Heist, which dedicates two of its six episodes to the scandal. What these episodes, titled “The Bourbon King” reveal is a story that will have any reasonable viewer shaking their head in disbelief, not at the “criminal masterminds” on display but the sheer incompetence of everyone who was involved. From the deluded thieves themselves, to the naive distilleries that employed them, to the hapless police who chased them, nobody comes out of this story looking good. It’s a full-scale comedy of errors, dialed up to 100 proof.

The facts of the case are as follows: A Buffalo Trace employee of more than two decades named Gilbert “Toby” Curtsinger began to take advantage of the company’s lax security policies and inventory management as early as 2008, swiping bottles and eventually cases of whiskey in many brands. He sold these bottles to a wide network of friends, acquaintances and shady characters, all of whom would go on to claim that they didn’t know the whiskey they were buying was stolen, which is obviously very believable. His steadily-growing operation revolved around a group of friends from a boozy softball league, who assisted in finding buyers even as Curtsinger ramped up the theft operation. It went undetected at Buffalo Trace even as Curtsinger was able to steal entire barrels of whiskey at a time, expanding operations with the help of a friend to also steal entire barrels from Wild Turkey. Together, these handful of guys, largely organized through Curtsinger, continued to steal hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of whiskey (even more, factoring in secondary market prices) for more than five years until “Pappygate” blew up into national news in 2013. At that point, so much Pappy Van Winkle finally went missing at once that Buffalo Trace noticed it was being robbed blind, and a police investigation began.

The older bottles of the “Pappy” lineup now routinely fetch $2,000-$4,000 on the secondary market.

The older bottles of the “Pappy” lineup now routinely fetch $2,000-$4,000 on the secondary market.

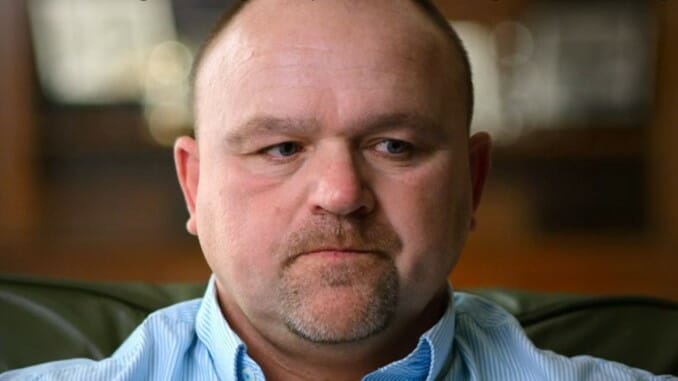

“The Bourbon King” is told almost entirely through Curtsinger’s fantastical point of view, allowing the ringleader an attempt to garner sympathy with “his version” of events. The result is a hilarious descent into toxic machismo, delusion, and greed, as Curtsinger attempts to cast himself as something between “noble father providing for his family” and “bootlegger folk hero”—one who ultimately got away with serving only 30 days of a 15 year jail sentence thanks to being granted shock probation. The frequent recreations we see throughout the documentary play more like Curtsinger’s private fantasies, transforming a group of schlubby yokels into a muscular parody of The A-Team, complete with several members being labeled as “the face” and “the mouth.” It is laugh-out-loud funny to see the transitions between this softball team as they’re depicted in the recreations—as a bunch of barrel-chested, tan, handsome muscle men pumping iron in homoerotic montages—to the sad reality of them as they are in real life, as portly middle-aged guys swilling beer as they’re being interviewed.

The difference is so stark, in fact, that it becomes a question of whether the director of these Heist episodes, Nick Frew, is attempting to glorify/romanticize the bond between these men, or not-so-subtly make fun of their delusional worldview, in which they see themselves as a majestic pack of wolves with half a dozen alphas. I’d like to think the truth is closer to the latter—the close-up shots of rippling muscles and softball montages just seem too gratuitous to not be satirical. I believe the director’s intent is to mock his subject’s desire for attention, but the irony is that much of the Netflix audience will likely miss that satire entirely, instead buying into Curtsinger’s romanticized fantasy perspective of his crimes.

Make no mistake, though, Curtsinger is a fool, and a vain one at that, who is never able to be honest with the documentarians about his actions and his motivations. He downplays the importance of the money as a motivator, claiming that he stole bottles out of some kind of altruistic desire to “help people get things,” as if he wasn’t selling those Pappy bottles at 1000% mark-ups. His home is a stockpile full of stolen whiskey, assault rifles and illegal steroids, which he and the members of his softball team all take in order to succeed at their craft. His best friend appears on camera and says the following: “As an athlete, I think ‘Okay, what can I do to be my best? Whatever it takes.’” He says that, with a straight face, as an explanation for why he would destroy his body with anabolic steroids in order to succeed in a recreational softball league for middle-aged men. This is the world that Curtsinger exists in, ringed by a collection of back-slapping good old boys heavily implied to be alcoholics throughout, none of whom seem to have any understanding of how text message records work. All are dutifully shocked when police present them with years and years of deeply incriminating communications.

Of course, it’s only natural for the audience to eventually ask “But how did these employers allow their workers to get away with stealing tons of product for more than five years?” One would hope that “The Bourbon King” would shed some light on this side of the story, but not a single talking head or official source from Buffalo Trace or Wild Turkey ever appears on camera to elucidate. The takeaway is clear—the companies are still embarrassed by the obvious deficiencies in security and management that allowed this to occur. The story is deeply embarrassing for Buffalo Trace in particular, where Curtsinger managed to simply visit the gift shop at night (which presumably had no security cameras?) and walk out with bottles of Pappy Van Winkle he could immediately unload for thousands of dollars, without anyone noticing. The employers ultimately can’t fall back on a defense that acknowledges the “tactical brilliance” of the thieves pulling an inside job, because they were ripped off by a group of guys with the mentality of drunk high school students. Curtsinger, likewise, casts shade at his employer of 20-plus years by describing the culture of thievery and intoxication that he says existed at Buffalo Trace at the time, simultaneously making an excuse for himself and implying that he wasn’t caught sooner because it was expected that all employees were stealing.

The documentary goes on to literally name other Buffalo Trace employees who also admitted to stealing copious amounts of bourbon, but apparently received immunity in return for information.

The documentary goes on to literally name other Buffalo Trace employees who also admitted to stealing copious amounts of bourbon, but apparently received immunity in return for information.

Kentucky police, meanwhile, get a depiction in “The Bourbon King” that implies the same sort of incompetence possessed by the thieves and their employers. Despite interviewing more than 100 Buffalo Trace employees, the detectives and their sheriff—portrayed here as a grandstanding attention hog who tried to use the case to prop up his reelection bid—don’t have the first clue which employees might have been involved in the inside job, effectively stymied by the good old boy code of silence. Curtsinger, meanwhile, seems to say that he kept right on stealing and selling whiskey for months or years during the investigation, clearly having zero respect whatsoever for his employer or the cops searching for him. And he probably could have kept it up indefinitely, if not for the fact that a $10,000 reward was eventually offered, which resulted in an anonymous tipster telling officers that Curtsinger literally had barrels of Wild Turkey sitting out in his backyard. Yes, this genius criminal enterprise is eventually taken down by cops wandering onto the property and finding the evidence sitting out in plain sight. It’s a fitting end to a deeply stupid crime story—the only way this story could have concluded, really. The police proceed to congratulate themselves over their detective work, which consisted of receiving a text message and then arresting the person named in said text message. Promotions all around!

In the end, “The Bourbon King” runs a feature-length 90 minutes or so, and is primarily amusing as a portrait of a place filled to the brim with toxic masculinity and straight-up buffoonery. There are few genuine figures of sympathy—even Curtsinger’s wife, indicted alongside him, is hard not to laugh at, with her claims that she was totally unaware that he was selling entire barrels of whiskey out of their garage, and housing those barrels in their own backyard. One can only imagine that she never noticed his safe full of cash, guns and steroids either. Curtsinger is a pathetic figure, somewhere in the pantheon of the Joe Exotics of the world, who says the audience should now pity him because “my 401k got smashed” as the result of his grand larceny trial and its related court fees. He barely even seems grateful for the fact that he’s still married and employed, rather than sitting in prison, serving the 15 years to which he was sentenced. It’s a uniquely American, white male form of entitlement, immortalized here forever.

In the end, I still don’t feel absolutely certain of the intent of Heist and “The Bourbon King” in telling Curtsinger’s story, but even if the episode is meant to simply provide an escapist fantasy about stealing whiskey with your meathead friends, it reveals more about the character of this man than it intends. Sadly, Curtsinger is not truly a unique character—rather, he’s possessed by the same pathetic delusions that have become a staple of American life. When you gaze at him, you see the worst of us reflected back.

It’s enough to make you want a slug of bourbon, in fact.

Jim Vorel is a Paste staff writer, and resident genre geek. You can follow him on Twitter.

For all the latest TV news, reviews, lists and features, follow @Paste_TV.