Poison in the Well of the Truth: Netflix’s Wild Wild Country and the Disturbing Story of the Rajneesh Cult

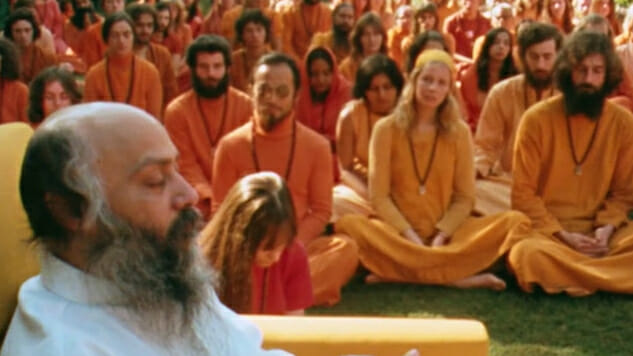

Photo: Netflix TV Features Wild Wild Country

Some documentaries are more dedicated than others to telling a story from multiple and opposing viewpoints. Netflix’s new docuseries Wild Wild Country is curiously far into that spectrum, and I say curiously because the primary interviewees—some members of the cult, some residents and law enforcement agents in the Oregon county where the Rajneeshpuram commune was located—seem to have inhabited two separate realities: If you made a Venn diagram, there would be virtually no overlap. In fact, nearly four decades later, the devotees of guru Bhagawan Sri Rajneesh still appear to inhabit a separate reality. Even the ones who fled the cult. Even the ones who were indicted for everything from biological warfare and voter fraud to attempted murder.

In the early 1980s, a guru with an ashram in Poona, India relocated to an 80,000-acre ranch outside the minuscule town of Antelope, Oregon. They were in the news constantly for one crazy thing or another—I was in elementary school when they established the commune of Rajneeshpuram and even I can remember people talking (mostly with derision) about the “brainwashed” Rajneesh cultists. By the mid-’80s they had disbanded, after a series of legal scandals that ranged from the weird to the outright horrible. Wild Wild Country tells their story in lavish detail, and since they were such a media curiosity at the time there is an incredible wealth of archival footage with which to work.

This might be a completely personal prejudice, but I find that the docuseries format can be hard to justify when the “episodes” are not clearly defined standalone units, or at least discrete “chapters” in a linear narrative. Wild Wild Country, it has to be said, is as vast and rambling as the Oregon wilderness where it takes place, and as a binge-watch it’s freaking exhausting. The subject matter is interesting. There’s footage galore from the heyday of the cult. The way Rajneeshee and non-Rajneeshee folks describe the commune and what it stood for and what it did in such irreconcilable terms is fascinating. Nonetheless, I wondered more than once why this spooled into a series versus a two-hour feature; it felt that padded and diffuse.

Oddly, it also left me with a feeling that I hadn’t learned much about the Bhagawan himself by the end of this long (looooong) series. The effect he had on certain people was clear, but the docuseries doesn’t really do a great job of explaining why, much less what he (at least allegedly) stood for. (Wikipedia’s handy if you end the series with the same feeling and want to know more. I was in elementary school when the events depicted in Wild Wild Country went down, but I had relatives in rural Oregon and I have clear memories of snide Rajneesh jokes at family get-togethers. I knew there was a sort of cult out there but I never really understood what was up with it. What was up with the Rajneeshee remains a subject open to serious debate, if the series is any indication.) Tightening this puppy up (a lot) to run in less time might have actually provided more concise information. All I got was that there was a “free love” element to it and an emphasis on meditation and humor, and there’s footage of rituals that appear to be centered on the release (often violent) of pent-up emotion.

The pivotal character in this story is Rajneesh’s personal secretary, Ma Anand Sheela. She’s extensively interviewed in this series and-just wow, is all. A confrontational and defiant personality, Sheela had a megaton of ego invested in her personal closeness to the guru, and in her defense of his goals, she consistently invokes bigotry and religious persecution against the commune. (While the residents of Antelope were pretty unified in wishing the commune would go away, they do not appear to have ever attacked Rajneeshpuram). The thing is, let’s say you’re a minority in a bigoted community, and maybe you face some ignorance, intolerance, or even hostility. That’s a thing. But in the “just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not out to get you” column, we have to place the fact that the people who converged on Rajneeshpuram committed serious crimes. And it seriously erodes your case for actual bigotry, racism, or religious persecution when you announce you are planning to take over the county and proceed to recruit homeless people from cities all over the country to join the commune specifically so they can vote in county elections, and then when the effort fails and you have no further use for the homeless people, to drug them en masse and dump them on park benches around nearby cities and towns. Sheela’s next move in the pursuit of social justice was to prevent non-Rajneeshee from voting by contaminating salad bars with salmonella, making some 700 people dangerously ill. After she suddenly left the compound, Bhagwan announced that she’d committed multiple crimes, including arson, illegal wiretapping and attempted murder. An investigator remarks that Sheela willingly confessed to these incidents, appeared to be giving completely honest testimony, and that she did not show the slightest bit of remorse: “This was definitely a person with no empathy.”

The people of Antelope and law enforcement both local and non-local (the FBI was involved) tell a story of a cult that took over a town by force. Once they bought the ranch they were legally entitled to incorporate it as a town, thus creating their own government and their own police force-they called it the “peace force,” but let’s just say they were not armed with daisy chains and mala beads, then engaged in bioterrorism, conspiracy to commit murder, massive immigration fraud, and voter fraud. The Bhagwan loyalists tell a story of a utopian community led by a Buddha-level master, and constant bigotry, racism, religious intolerance, and injustice menacing them from the outside at every turn. They say the truth is usually somewhere in the middle, but this is a story with almost no middle whatsoever.

So this is where we reach into the interesting and timely bit at the heart of this strange episode in Oregon history. Both realities were at least partly real. Did the tiny, conservative, white, ranching-focused and largely retirement-aged community of Antelope simply object to a bunch of outsiders who wore weird clothes and took strange Indian names and had a lot of sex in public because they were different?

Yep. And it didn’t help that the commune members were constantly circling the town with AK-47s and that they considered poisoning people an acceptable practice, especially since the cult came to the States while Jonestown was still fresh in people’s minds.

Did the Rajneeshee commit crimes against the community and the government?

Yeah! And it didn’t help that the neighbors had an axe to grind with the freaky-deaky invasion of “their” land.

So we have a rambling, if generally thorough, document of a strange historical event, largely recounted by the people who were there. The documentary does not really take sides and it certainly leaves open to interpretation which side of the story holds more water. My main quarrel with Wild Wild Country is the sheer bulk of the footage, which at a certain point begins to obscure the issues more than clarify them. But the takeaway questions are certainly timely enough: How do we, as a nation, handle immigration and integration? More importantly, why do we make the choices we make in that space? What happens to the hard-and-fast constitutional argument for separation of church and state when a religion is allowed to form its own government and arm its own military? Is it religious persecution when you’re investigated for an attempted murder you actually did attempt? Do the complaints of one side invalidate the grievances of the other?

For me, the truly intriguing question is one I feel Wild Wild Country addresses only in the most oblique manner, primarily through an interviewee who was imprisoned for the attempted poisoning of Rajneesh’s personal physician. The woman describes how it took several years after she fled the commune (and dealt with some family tragedy) that she began to feel a kind of trance had been lifted from her and that she returned to herself. That’s where I would have liked to dig in. What creates a guru like Bhagwan Sri Rajneesh and confers this Svengali-like power on him? Some of his devotees will still tell you he was basically an enfleshed god. He was a god who amassed millions of dollars, owned a fleet or Rolls Royce cars and two Learjets, spoke to his followers (when he spoke at all) from a throne, and clearly mesmerized thousands of people.

But whether it was Ma Anand Sheela who was solely responsible for the poisonings, wiretapping, illegal immigration schemes and general stance of entitled aggression toward a community she never tried to understand, or whether there was something much more complicated than that going on (and there surely must have been), what does emerge clearly is that lies are often as poisonous as salmonella, or the bacteria-vectoring beavers the cult allegedly tried to put into the Antelope reservoir. Once there’s literal and figurative poison in the well, it becomes difficult to cast yourself as either persecuted or enlightened.

Wild Wild Country is now streaming on Netflix.

Amy Glynn is a poet, essayist and fiction writer who really likes that you can multi-task by reviewing television and glasses of Cabernet simultaneously. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.