Here’s Why You Should Never Watch WWE Again

Screecaps from YouTube

To most Americans, pro wrestling means one thing: Vince McMahon’s WWE. When McMahon bought his father’s wrestling promotion in 1982, he kicked off a systematic takeover of the American wrestling industry, and in less than a decade rewrote the fabric of the whole business in controversial fashion.

For decades the American wrestling market was split between various different regional promotions. They didn’t always get along or work closely with one another, but for the most part they cooperated to some extent, respecting each other’s regional claims and often recognizing a mutual top champion. Even after McMahon’s father broke away from the National Wrestling Alliance in 1963, and formed the promotion then known as the World Wide Wrestling Federation, he stayed within his own territory in the Northeast, and even booked the NWA World champion on some of his shows. The WWWF’s relationship with the NWA and Verne Gagne’s AWA was never great, but they were able to coexist for decades.

With the advent of cable TV in the ‘80s, it became easier than ever for a regional wrestling promotion to go national. That was exactly Vince McMahon’s plan when he took over the company in 1982, by which time it was known as the World Wrestling Federation (WWF). By 1983 McMahon had started syndicating WWF programming in markets outside its traditional territory. He started poaching top stars and personalities from other promotions, most notably Hulk Hogan, and started to tour nationally. He basically started breaking all the agreements that had governed pro wrestling for most of its history, and by 1990 there were only two major wrestling promotions left in America: McMahon’s WWF and Ted Turner’s World Championship Wrestling.

It was largely a one-sided war until 1996. WWF was firmly established as the dominant national brand in wrestling, whereas the only markets where WCW came close to matching WWF’s popularity was in its traditional territory of the Southeast. That started to change in 1994, when WCW signed away Hulk Hogan. The tide fully turned two years later, when WCW brought in two more of WWF’s top stars, Kevin Nash and Scott Hall, and kicked off the NWO angle that briefly helped them overtake WWF on a national level. WCW beat WWF in the ratings consistently for almost two years; WWF retook the lead in 1998 on the backs of Steve Austin, The Rock, and other top stars, along with a shift in direction away from the child-focused cartoon world the WWF was known for, and into an edgier, more lurid sensibility that appealed to teen and twentysomething viewers.

The war between WWF and WCW became one-sided in 1999, with McMahon roundly defeating his competition every week. After greatly overextending their budget and suffering from terrible creative and management for a few years in a row, WCW was sold on the cheap to McMahon in 2001, putting an end to his only real competition.

From that point on McMahon essentially had a monopoly on the American wrestling business. His only challenges came from two surprising sources: the World Wildlife Fund, the animal rights charity who had uneasily shared the WWF trademark with McMahon since 1982, and who won a lawsuit in 2002 for the sole rights to the initials; and from his own fans, who quickly lost interest in pro wrestling after WWF no longer had competition, and who tuned out in droves starting in 2001.

In 2002 McMahon rechristened his company as World Wrestling Entertainment, a name it still holds today. It had already lost a large number of its viewers since the highpoint of 2000, and despite being the only wrestling promotion with national television for years after the end of WCW, WWE continued to lose viewers from 2002 on. New companies sprang up to help fill the void left by the 2001 deaths of WCW and the large indie group Extreme Championship Wrestling, but neither Ring of Honor—a small but passionately supported indie based out of the Northeast—nor Total Nonstop Action—a Nashville-based promotion that explicitly tried to recapture the late ‘90s feel of WCW, and received a great national TV time slot on the Spike network despite actively alienating the most dedicated and vocal wrestling fans—came close to posing a legitimate threat to WWE.

Since he bought WCW, Vince McMahon’s greatest threat has been himself. WWE’s audience saw a slow, steady erosion throughout the ‘00s and early ‘10s, but it’s greatly accelerated over the last five years. Either through hubris or incompetence, the company has failed at making new stars for most of the last decade, and still relies on names from the past to prop up its major shows. And when its fans do rally behind a wrestler, McMahon has no problem trying to kill that wrestler’s popularity if it isn’t somebody McMahon himself wants to push as a top star. Despite this the company is also highly profitable; it’s been able to ride the wave of escalating TV rights for live sports, signing deals with Fox and the USA Network that guarantee billions of dollars over the next few years. By all metrics of fan engagement, WWE is less popular than it’s ever been, and yet it’s making more from its TV deals than ever.

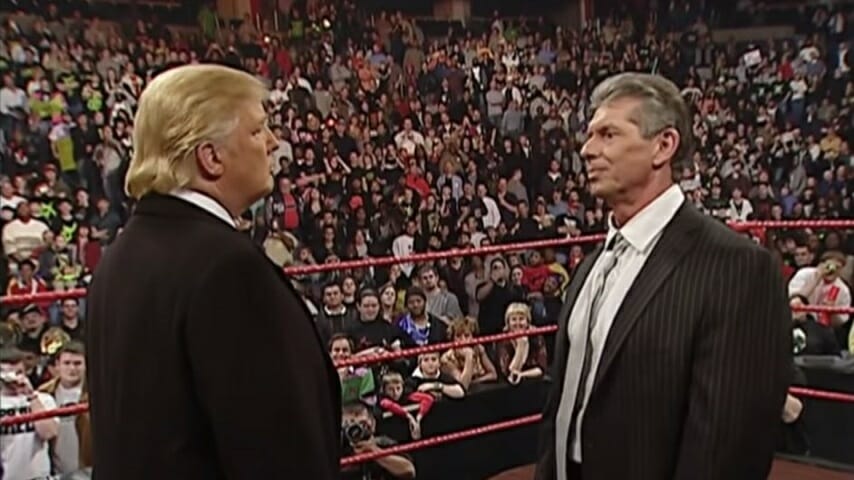

Vince McMahon and WWE have absolutely earned that collapse in popularity. No matter how good the in-ring content can be, WWE’s storytelling has been nonsensical for years. Despite his huge successes in the ‘80s and late ‘90s, Vince McMahon’s legacy at this point is that of a stubborn tyrant who is utterly out of touch with the wrestling audience, and who has become politically toxic because of his mistreatment of labor and close connections to Donald Trump. At this point it doesn’t make any sense to watch or support WWE; it’s a terrible product run by unlikable people who openly hold their audience and workers in contempt.

Let’s talk specifics, though. Let’s get into the details. There are dozens of reasons not to watch WWE, or support the McMahon family. Here are only six of them. And we won’t even bring up the Trump stuff again, even though Linda McMahon, Vince’s wife and the former CEO of WWE, served in his administration. Actually, we’ll bring the president up once more, and only because it’s directly related to the current crisis upending the entire world. And yes, that’s obviously going to be the coronavirus.

Here are just a few reasons why you shouldn’t watch or support WWE.

1. Their Atrocious COVID-19 Response

It’s no surprise that the McMahon family would have a dangerously irresponsible reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic. After all, they’re closely tied to Donald Trump, who has consistently tried to downplay the severity of the virus. While other wrestling companies have regularly tested its crew and talent, and in many cases stopped running shows altogether during the pandemic, WWE holds events regularly at its Performance Center in Orlando, and didn’t perform any testing until after a COVID-19 outbreak hit the company in late June. Dozens of people affiliated with the company have tested positive since late June, which resulted in a temporary delay in the company’s taping schedule. This came several weeks after WWE started using Performance Center trainees and NXT wrestlers as an audience for its main roster shows, having them stand around the ring behind plexiglass barriers with no masks on. Wrestling’s obviously a high risk activity when it comes to spreading a virus, but that risk only goes up if you have a crowd without masks. WWE has since reversed course on masks, requiring employees and audience members to wear them, and for wrestlers to wear them when they aren’t performing on camera. The company also says it will start testing all employees and wrestlers before all tapings going forward. The fact that it took months for that to become the procedure, and only after dozens of employees caught the coronavirus, is another huge indictment of WWE and how it treats the wrestlers with whom it couldn’t exist. Obviously the safest thing to do during these times is to not run wrestling shows at all, as we’ve seen New Japan and Ring of Honor do; WWE might be able to survive that long-term, but it would most likely cost them their TV deals, and lead to even more layoffs. (Yes, WWE laid off many of its wrestlers during the pandemic. More on that later.) WWE’s main American competition, AEW, has run shows every week during the pandemic as well, and with an audience of wrestlers, family and friends that almost never wear masks or distance themselves. It’s a bad look for them, too, but to AEW’s credit it’s consistently tested everybody who’ll be at ringside, backstage, or in-ring before every TV taping, and so far there have been no reports of anybody at their tapings coming down sick. There’s no excuse for WWE not regularly testing until the last week, other than wanting to save money and not thinking the virus was a big deal. This kind of mistreatment of its wrestlers and employees isn’t unusual at WWE, though. For instance, there’s…

2. The Absurd Way It Treats Its Wrestlers

A talented labor lawyer with some money behind them could have a field day challenging WWE’s contracts. Despite signing wrestlers to exclusive contracts and dictating almost every aspect of how they’ll perform and be presented, WWE still legally classifies its wrestlers as independent contractors. That means they receive no benefits; WWE will cover injuries that happen at work, but otherwise wrestlers are responsible for their own medical care. WWE tells them exactly where to go and when to be there, but only provides or pays for transportation on overseas tours or for wrestlers with enough clout to request it during contract negotiations. If a wrestler is injured or can’t perform for any reason, WWE will often extend their contract by the amount of time they miss in a legally dubious practice that apparently has yet to be challenged in court by any of the wrestlers. Yes, WWE generally pays better than other wrestling promotions, and they aren’t the only one that uses the independent contractor designation; they originated that tactic, though, and with the amount of money the company makes it could easily afford to treat its wrestlers like the employees they actually are—especially since its massive current TV deals kicked in with Fox and NBC Universal last year. Without its wrestlers WWE wouldn’t be in a position to sign those TV deals or produce content for its streaming network, and yet it treats almost all of them as interchangeable cogs. Compared to the major professional sporting leagues like MLB, NFL and the NBA, WWE pays out a drastically smaller percentage of its profits to its talent. Players in those leagues all have unions, something that doesn’t exist in wrestling; until one does, expect WWE and other promoters to continue to exploit and underpay them.