Cocaine Art, Eden and Sex at MoMA

The Fascinating Delirium of Hélio Oiticica

All images courtesy of the Art institute of Chicago Visual Arts Features Hélio Oiticica

February of 1994 wasn’t a great month for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in Manhattan. The institution laid off nearly ten percent of its staff, reduced its hours of operation, temporarily closed its library, and had to cancel a couple of exhibitions.

One of them was a retrospective of the Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica (1937-1980), who was still relatively unknown in North America. The exhibition had been traveling throughout Europe since 1992, with stops in Rotterdam, Paris, Lisbon and Barcelona, and had just arrived in the U.S. the year before, when it opened at the Walker Arts Center in Minneapolis in October. The Guggenheim would’ve been its next stop.

Kathy Halbreich, then-director of the Walker, couldn’t hide her frustration: “Here’s an artist who is less well-known than he should be,” she told the New York Times, adding that the show would no longer be reviewed, since critics were waiting for the exhibition to open at the Guggenheim to review it.

Twenty-two years later, they are finally getting their chance.

Last October, Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium opened at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh to great public and critical acclaim. Art critic Stephen Heyman praised the exhibition writing on Vogue that “the Brazilian genius who pioneered installation art is finally getting his due.” Art Daily said the “visually arresting” show was like an “experience unlike any other.” Hyperallergic picked the show as one of its top exhibitions of 2016. The three-month stint in Pittsburgh was only the first of three legs of the artist’s first major retrospective in over two decades: it will travel to The Art Institute of Chicago in mid-February and to the Whitney in New York City in July.

Oiticica is no stranger to the New York City public. In the summer of 1970, he was part of INFORMATION, a group show at MoMA whose goal was to “extend the idea of art beyond traditional categories.” Oiticica didn’t take that concept lightly: in “Barracão Experiment,” he built 28 nests where museum-goers were encouraged to go in to rebuild their own nests and relax, all in the name of creativity. On the opening day, former Second Lady Happy Rockefeller opened one of the nests and caught a couple having sex.

But with To Organize Delirium, for the first time an exhibition includes Oiticica’s New York years in depth, according to the Carnegie’s director Lynn Zelevansky, also one of the show’s curators. “There hasn’t really been a fully comprehensive exhibition of his work that would tell people what his whole career was like, because when you only see a part of it, or when you only see one, two or three works, you can’t fully understand what an artist’s project was,” she says.

The exhibition honors Oiticica’s evolution, showing three distinct phases of the artist: Rio de Janeiro (1955-68), London and New York (1969-78), and the return to Rio (1978-80).

He began as a painter, and his work “starts off somewhat in a formal way, as a neo-concrete artist working with rectangles,” says art historian Paula Braga, author of three books on Oiticica. Soon, “it looks like the rectangles want to get out of the paper, and move into space,” she says referring to colorful panels suspended from the ceiling that marked his early work, and that he made for people to walk through them.

“He leaves the bi-dimensional universe, which is the paper; moves to 3-D, when he starts hanging those shapes from the ceiling; and then moves beyond 3-D, when he puts those colorful structures on the body of a samba dancer,” Braga explains, making reference to “Parangolés,” one of Oiticica’s best-known pieces.

(Color plays a big part in his early work: The Body of Colour, a 2007 exhibition organized by the Museum of Fine Arts Houston in collaboration with London’s Tate Modern, explored Oiticica’s original use of color. His career, Roberta Smith wrote in The New York Times, was “fueled by a passion for color as theoretical as it was obsessive.”)

By 1971, he moved to New York to run away from the Brazilian coup d’état of 1964, and became fascinated with the post-Stonewall gay liberation movement, and with lower Manhattan’s underground gay scene. He was inspired by queer cinema pioneer Jack Smith, worked with gender illusionist Mario Montez — Andy Warhol’s first drag superstar — and he denounced the commercialization of the queer art scene in New York. Decades before today’s celebrity scandalous tapes, Oiticica filmed himself masturbating, having sex with another man, and having the time of his life with cocaine— all of which can be seen in the excellent 2012 documentary Hélio Oiticica, directed by his nephew César Oiticica Filho. (Explaining 1973’s “Cosmococa,” Oiticica proclaims “Cocaine is the light,” snorting happily as he used the drug to make drawings on top of Weasels Ripped My Flesh, an album by the band Mothers of Invention.)

“As the political situation [in 1964’s Brazil] gets worse, and the dictatorship comes in, he gets more socially oriented,” explains Zelevansky. This can be seen in one of the highlights of the exhibition: “Tropicália” (1966-67). Done in massive scale, “Tropicália” consists of two “Penetrables” (maze-like structures) set in sand, where viewers walk around tropical plants, live parrots, pebbles and a TV set. It’s inspired by houses in the favelas, built with wood and decorated with cheap colorful fabric: it critiques the notion of a stereotypical Brazil as a tropical paradise.

Brazilian musician Caetano Veloso borrowed the title for a song, which became the theme of resistance against the military coup. The term “tropicalism” “becomes a whole movement in all the arts and signifies the political [anti-establishment] position,” says Zelevansky.  (Curiously, Oiticica didn’t like the term. “The burgeois, the sub-intellectuals, idiots of all sorts” now preach tropicalism without knowing what it is, he wrote in 1968.)

(Curiously, Oiticica didn’t like the term. “The burgeois, the sub-intellectuals, idiots of all sorts” now preach tropicalism without knowing what it is, he wrote in 1968.)

Another highlight is “Eden” (1969), which he described as a “mythical place for feelings, for acting, for making things and constructing one’s own interior cosmos.” Eden is another massive multi-sensorial installation – rarely shown because of it size – where people can navigate through “Penetrables” while walking on sand, leaves, and water.

Oiticica wanted to create a new kind of relationship with the viewer, whom he called the “participator,” and “have a kind of social interaction and notion of social life around the art,” says Zelevansky – though Oiticica’s goal was never really art. “My aim,” he said in 1979, “is to trigger states of invention.”

Muri Assunção likes to write about arts, culture and all things LGBTQ. He was born and raised in gorgeous Rio de Janeiro, but has lived in Manhattan’s gayest zip codes since the late ‘90s. His work has appeared in Towleroad, Men’s Journal and others. Follow him @muriassuncao.

About the photos:

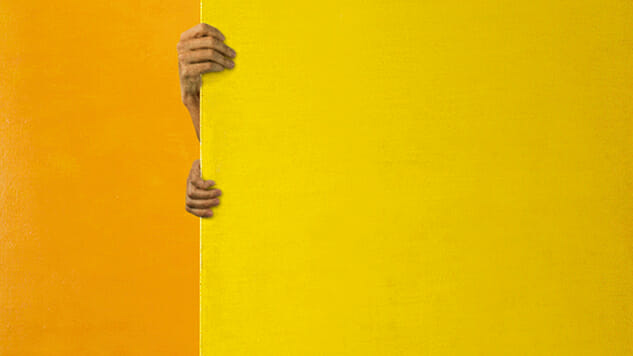

Main + Body Photo 2: Hélio Oiticica. PN1 Penetrable (PN1 Penetrável), 1960. César and Claudio Oiticica Collection, Rio de Janeiro. © César and Claudio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro.

Body Photo 1: Hélio Oiticica. PN27 Penetrable, Rijanviera, 1979. César and Claudio Oiticica Collection, Rio de Janeiro.

Body Photo 3: Hélio Oiticica. GFR 022 and GRF 028, 1955. Collection of Diane and Bruce Halle; Hélio Oiticica. Grupo Frente 24, 1955. Collection of Donna and Howard Stone.

Body Photo 4: Luiz Fernando Guimarães wearing Oiticica’s P30 Parangolé Cape 23, M’Way Ke, at the West Side Piers, New York, 1972. Private Collection. © César and Claudio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro.

Body Photo 5: Hélio Oiticica. Filter Project—For Vergara (Projeto filtro—Para Vergara, 1972) (cat. 63) at Galerie Lelong, New York, 2012. Courtesy of César and Claudio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro, and Galerie Lelong, New York.

Body Photo 6: Hélio Oiticica. Penetrable, Magic Square 5, De Luxe—Invention of Color, 1978. César and Claudio Oiticica Collection, Rio de Janeiro. © César and Claudio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro.