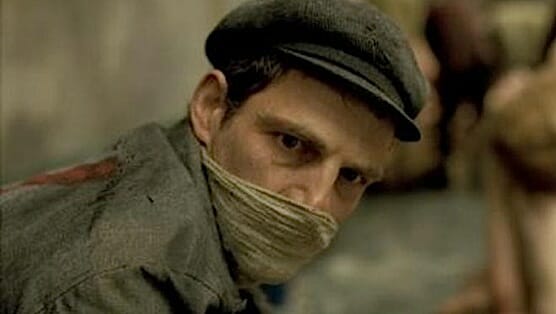

Son of Saul (2015 Cannes review)

The challenge of the Holocaust drama isn’t conveying the importance of the subject but recognizing the necessity of encapsulating that importance in a new way. With so many movies focused on one of the great tragedies of humanity, it’s inevitable that familiarity will creep in, the chronicling of atrocities eventually becoming more numbing than shocking or illuminating. Although there are plenty of worthy Holocaust films, the solemnity of the storytelling risks becoming sanctimonious, suffocating. What new can we possibly learn about those well-documented horrors?

What elevates Son of Saul is that first-time feature filmmaker Laszlo Nemes has constructed a new way of grasping the insanity and senselessness of those long-ago crimes. But what’s remarkable is that, rather than taking the obvious tack and investing his scenes with expected images of horrible suffering, he captures the terror of the concentration camps in an almost offhand way. Son of Saul is rightly called a Holocaust film, but it’s not quite like one we’ve ever seen. Through some stunning technical achievements, Nemes has made a film that more closely aligns itself with the workplace drama and the intimate war movie.

Saul is played by Géza Röhrig, an actor whose weary, determined eyes draw comparison to Jean-Paul Belmondo’s. A captured Jew, Saul works in the concentration camp as part of the Sonderkommando—essentially, a man forced to help facilitate the Nazis’ systematic murder of its prisoners. But in keeping with Son of Saul’s less-is-more approach, we don’t get a sense of Saul’s feelings about his difficult job. All we see are those eyes, or the back of his head as he moves from task to task. Filmed often in close-up with handheld cameras, Saul isn’t intended to be a complex character. As envisioned by Nemes, he’s merely a man trying to survive.

The crushing routine of Saul’s life receives an unexpected jolt when he takes special notice of one young corpse in his care. Looking at the beatific child, Saul feels a kinship, which at first is unexplained. Finally, he reveals to a colleague that the boy is his son and that he wants to ensure he receives a proper burial. This strikes others in the camp as odd—Saul doesn’t have a son, does he?—but Son of Saul never makes it easy to know what to believe. Perhaps Saul is lying? Or maybe he’s seeing in this corpse a past his fellow prisoners know nothing about. Or, perhaps, he’s just going insane.

No matter the truth, Saul begins a single-minded quest to find a rabbi in the camp and orchestrate this clandestine burial—all the while hopefully avoiding suspicion from his German captors. But Son of Saul isn’t The Great Escape or some other rousing World War II escape picture. It’s a grittier, more immediate film that strips away the solemnity of the Holocaust movie by plunging us into Saul’s moment-by-moment mission. And Nemes’ camera—the cinematography is by Mátyás Erdély—emphasizes long takes and shallow focus so that we can’t make out Saul’s harsh environment but can always sense it. We’re attached to Saul’s hip, practically hanging on for dear life.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-