Cocktail Queries: What Is “Fassionola,” Tiki’s Most Mysterious, Misunderstood Ingredient?

Photos via Unsplash

Cocktail Queries is a Paste series that examines and answers basic, common questions that drinkers may have about mixed drinks, cocktails and spirits. Check out every entry in the series to date.

In Raiders of the Lost Ark, Indiana Jones mentions at one point to his classroom full of adoring students that the greatest threat to an archaeologist’s work typically isn’t danger to life or limb, but the damaging effects of folklore. The stories that make up an oral tradition have the power to keep awareness of a thing alive across generations, but also distort the truth of its actual origins. This is often just as true of the alcohol market as well, where genuine historians are all too frequently ignored in favor of more easily digestible factoids that make for a good, repeatable story. Look no further than the persistent work of a historian like Martyn Cornell over literally decades to set the record straight about India Pale Ale’s origins. He’s still plugging away at it, and tons of people still simply ignore his primary sources and repeat old myths about IPA instead. They prefer the colorful myths to the boredom of the truth.

The world of tiki cocktails has a tendency to be rife with this kind of historical confusion and mythmaking. So many of the classic drinks of the genre weren’t even properly codified and documented until the last 25 years, following the publishing of books like Beachbum Berry’s Grog Log in 1998 and Sippin’ Safari in 2007. Many of those drinks had existed in a twilight status, remembered by those who had sampled them during tiki’s heyday, but with recipes that were forgotten, dumbed down or repeatedly bastardized until they bore almost no resemblance to their original versions. Today, accurate recipes (and new drinks inspired by them) have staged a comeback, but tiki’s occasional sidetracking down oddball rabbit holes over the decades has made an enduring impression on the genre as well. Eventually, when things are done “wrong” for long enough, they become part of the canon in their own, weird way.

This goes doubly for a genuinely mysterious ingredient like the legendarily confusing fassionola. Perhaps you’ve heard of fassionola, or perhaps you’ve even seen it referred to as “passionola” in the past. In the city where I live, there’s even a brewery occasionally making a “fassionola gose.” Perhaps you’ve seen it as a golden syrup, one that is obviously based around passion fruit. Or maybe you think of it as a red syrup with some of the same flavors, but more of a grenadine-like vibe. Maybe you’ve even seen a green syrup at some point, going by the same name. As it turns out, they’re all connected to the history of what is undoubtedly one of the tiki world’s most confusing and frequently misunderstood ingredients. Thankfully, much of this mystery has now cleared up, thanks to the recent publishing of a new book, Fassionola: The Torrid Story of Cocktails’ Most Mysterious Ingredient, by Gregorio Pantoja and Martin S. Lindsay.

But when it comes to setting the record straight on fassionola, Pantoja and Lindsay have their work cut out for them, because their new offering is being projected out into a void that contains decades of misinformation on this topic. Well-meaning articles written by bartenders and drink writers have consistently repeated a lot of myths, misconceptions and outright falsehoods regarding fassionola, through no particular fault of the writer. These drink writers are frequently interviewing bartenders for these pieces, and those bartenders pass along the industry legend stories they know, many of which have taken on lives of their own. The new Fassionola book SHOULD create a concrete timeline of who, what, when and where for fassionola as an ingredient, but the reality is of course that the stories will be very difficult to dismiss even with an accurate, fully researched historical account now available. Stories are stubborn; people don’t like to set them aside even when they’re shown to be inaccurate. It could take a generation before the majority of tiki geeks are sharing the accurate version of this story.

As an example of a piece that shares some incorrect information, look no further than this recent article from just last week on the classic Cobra’s Fang cocktail. The bar operator who is quoted passes along a number of incorrect things, such as saying that the “nola” in the ingredient’s name is a reference to New Orleans because it was invented there. Nor was it created by a legendary tiki proprietor like Donn Beach. That simply isn’t accurate, but I have no doubt that’s the story as this bar owner learned it.

The particular problem with accurately describing fassionola is that historically, there were multiple versions of that product, which results in different people picturing and describing entirely different products when they hear the name. Nor can you state simply that “fassionola contains ___ and ___,” because the original recipes were secret. It’s not as simple as just saying that “fassionola contained strawberries”–maybe the red version did at some point, and maybe not. Nor was the red version used in a Cobra’s Fang, as seen in the article above. The one and only indisputable thing is that this syrup involves passion fruit, but I’ll expound on that in a moment.

For now, let’s answer the most basic of all questions: What is fassionola, really, and who created it?

The Birth of Passionola

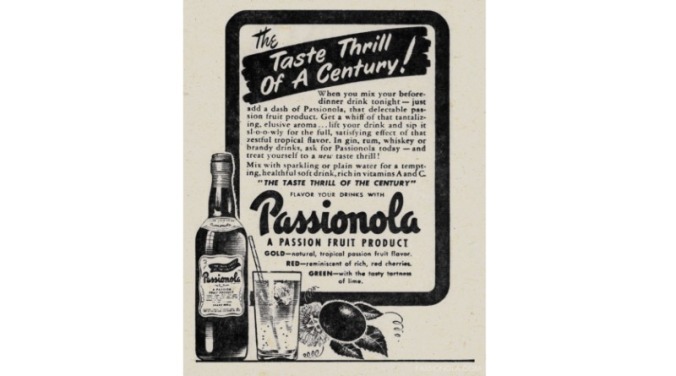

Before there was fassionola, there was Passionola. The latter is capitalized because it was a trademarked brand name, and quite a successful one over the course of decades. For close to 30 years, in fact, bottles of Passionola were frequently spotted in bars and grocers all over the U.S. Fascinating that it could be so frequently forgotten today, right?

The Passionola brand was created by husband and wife team Victor and Eugenie Kremer, debuting by 1931, according to Pantoja and Lindsay’s Fassionola. Victor Kremer was a sort of renaissance man of many talents and specialities–he had been a pharmacist, film producer, music publisher and seller of clay products for building materials by the time he and his wife got serious about selling agricultural goods. They had moved to the seaside community of Cardiff-by-the-Sea, north of San Diego, in the mid 1910s, where Eugenie eventually experimented in growing newly available plants such as avocado and passion fruit, which had recently been introduced from New Zealand. Becoming enamored with the exotic promise of the latter, the Kremers began to sell products such as passion fruit marmalade, jelly and concentrated juice on a small scale, and then gradually expanded their new plantation business. One of their most popular products became the passion fruit syrup they called Passionola–no reference to New Orleans at all. It’s unclear whether the Passionola they were producing at this time was made with only passion fruit or contained any other tropical fruit influences, because its recipe was secret, but we know that it was a golden-colored syrup.

This syrup was one of quite a few similar fruit syrups on the market, which were used for any number of purposes–to top ice cream or sherbet, as part of fruit punch mixes or cake icing, and as an ingredient at soda fountains. Competitors included East Coast companies like Hay’s, which made the popular Hay’s Five Fruit syrup, or the original incarnation of Leo’s Hawaiian Punch, which was created in 1931 in Los Angeles.

Something momentous happened in 1933-1934, however, which would change the arc of the Kremers’ lives forever: The prohibition of alcohol in the U.S. ended, and Donn Beach began mixing up his “rhum rhapsody” cocktails at Don the Beachcomber in Hollywood. And as fate would have it, Kremer’s Passionola was being bottled a mere eight blocks away from Donn’s original, iconic bar.

So yes, Donn Beach definitely had access to Passionola, and the unearthed recipes eventually dug up by Jeff Berry and Donn’s third wife, Phoebe Beach, demonstrate this. At Don the Beachcomber, Passionola (and eventually fassionola) was used in drinks such as Don’s Pearl, Cherry Blossom, Pi-Yi, Q.B. Cooler and the original Rum Barrel. Perhaps the most enduring use, though, was in the Cobra’s Fang, an intoxicating blend of Jamaican and Guyanese rum with falernum, lime and orange juice, absinthe and Passionola. The drink has been well represented today in the modern tiki revival, albeit with passion fruit puree or syrup typically stepping into the place of the Passionola. Meanwhile, other early tiki impresarios were also making use of Passionola. “Trader Vic” Bergeron agreed with Donn that Passionola stood out as a different ingredient from plain passion fruit juice or syrup, and didn’t use them interchangeably. Of the original Trader Vic cocktails, the Tonga Punch is the only that specifically calls for Passionola.

At the same time, Passionola also simultaneously had a hand in some of the recipe mimicry/thievery that would eventually lead to mass confusion in the history of tiki cocktails. One of these key moments was in 1939, when New York restaurateur/nightclub maven Monte Proser opened his own “Beachcomber” restaurant in New York, ripping off as much of Donn’s theming and cocktails as he possibly could in the process. Undeterred by subsequent lawsuits, Proser went on to serve and widely popularize rip-off versions of many of Donn’s most beloved drinks, particularly the Zombie cocktail. And in Proser’s version of the Zombie, it prominently calls for a large amount of Passionola–this, despite the fact that the original Zombie contains no passion fruit at all, instead having only lime and grapefruit juice. This version of the Zombie subsequently spread far and wide, particularly on the East Coast, including in bottled commercial versions from brands like Ronrico Rum. Because Donn’s original version was a secret recipe, one that wouldn’t be unearthed until more than half a century later, it was this stolen version of the Zombie that ultimately played into widespread consumer confusion on what exactly a “Zombie” cocktail was supposed to be.

Passionola and the Hurricane

There’s a lot of inaccurate information on the web when it comes to the history of many cocktails, tiki-adjacent or otherwise, but few cocktails have their histories wrongly detailed quite as often as the Hurricane. The drink has consistently been associated with Passionola/fassionola over the years, and indeed is the first place many drinkers heard/saw the term, but the legitimate history of how this came to be has only now come to light in Pantoja and Lindsay’s Fassionola.

To begin with, there were other cocktails by the name of “Hurricane” before the one now famously associated with New Orleans. Prior Hurricanes found in London and Mexico are built around ingredients such as gin, scotch whisky and creme de menthe, and bear no resemblance at all to what the drink would become.

The modern Hurricane became a tropical drink evoking the South Seas after the widespread success of the 1937 John Ford film The Hurricane … on which Donn Beach had actually served as a technical advisor for set decoration, thanks to his expertise on the South Pacific. Subsequently, various tropical bars with the name “Hurricane” began to pop up around the country. Nightclub proprietor Mario Tosatti was one of these entrepreneurs, opening up the Hurricane Club to service the 1940 season of the New York World’s Fair. He served all sorts of drinks largely stolen from Don the Beachcomber, but at the same time also seemingly invented the namesake cocktail: The rum-based Hurricane, which now had the recipe any tiki geek would recognize–Jamaican rum, lime and lemon juice, and quite a lot of Passionola.

But what about New Orleans? The famous Pat O’Brien’s of New Orleans has over the decades staked its claim as the creator of the Hurricane, but it doesn’t seem to have started pouring the drink until a couple of years after it first appeared at the 1940 New York World’s Fair. By the time it got to Pat O’Brien’s, the recipe had also changed a bit–it now used only lemon juice, and it was being made with a new version of Passionola, the newly available Passionola Red syrup. Pat O’Brien’s continued to use Passionola Red for decades until it became unavailable, then cycling to the use of other syrups, before making their own in-house passion fruit syrup product to ensure access to the key ingredient of their most famous drink.

Passionola Becomes Fassionola

As Victor and Eugenie Kremer expanded their passion fruit business, they diversified the lineup. Passionola Red was described as “reminiscent of rich, red cherries,” while Passionola Green featured “the tangy tartness of lime.” It’s still not entirely clear what was in either, but they were both still based around passion fruit with additional fruit juices/colorings, and the Passionola Red in particular was heavily featured in many cocktails beyond the Hurricane in New Orleans.

The Kremers continued to operate their business until 1957, when both Eugenie and Victor Kremer passed away. Their company, by then called Old Tavern Foods, merged with Jacob V. Dunn Company in 1960, whose owner Jacob V. Dunn filed for the trademark of “Fassionola” in 1962. The product was subsequently reintroduced to the market from 1964 onward as Fassionola, still available in Gold, Red and Green variants. It continued to be offered by Jacob V. Dunn Co. until his death in 1986, and the Fassionola trademark was abandoned the following year. In these decades, the popularity of tiki cocktails hits rock bottom and many of the recipes of the era are forgotten or bastardized beyond recognition.

Fassionola was revived in a limited capacity, however, when the San Diego-based Jonathan English Co., known for their sweetened lime juice, tracked down and bought the recipe in the early 1990s. From 1995 onward, Fassionola has again been available from Jonathan English Co., although access to consumers is limited and mostly conducted through Ebay of all places. You can still buy a bottle of this Fassionola brand through Ebay from Jonathan English Co. today.

As for the original Passionola created by Victor and Eugenie Kremer, it too now lives again thanks to Pantoja and Lindsay’s Fassionola book. The pair of authors has officially recreated the closest version to the original Passionola product they could, and have just within the last month put out their first commercial releases of this newest iteration of Passionola. It is a rather exciting moment for us tiki cocktail geeks, to know that an iconic product off the market since the late 1950s is now perhaps within reach once again. Of course, many bars and cocktail bloggers have over the decades taken to producing their own fassionola offshoots containing all sorts of fruit influences, which is one of the reasons why it had become such a confusing ingredient in the first place. One wonders if all these bars will simply continue using their homemade fassionolas, or try to revamp them to match the newly unearthed historical version.

Having read Fassionola: The Torrid Story of Cocktails’ Most Mysterious Ingredient, I can heartily recommend diving even deeper into this subject by purchasing Pantoja and Lindsay’s impressive tome. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the actual book doesn’t have an extremely tight central focus on merely Passionola, being instead filled with asides about specific minor historical figures, bootleggers, starlets, nightclub and bar proprietors, and long-defunct alcohol brands. It ultimately explores any figure or topic important to the history of tiki cocktails and culture, but for the kinds of cocktail geeks who would read a book about fassionola, this is all going to be welcome information.

So, there you have it: The real history of Passionola/Fassionola, and its tangled legacy in the world of tiki cocktails. Are we all ready for a drink now?

Jim Vorel is a Paste staff writer and resident beer and liquor geek. You can follow him on Twitter for more drink writing.