Lines Between Animation and Skateboarding: Interview with Tomas Pajdlhauser

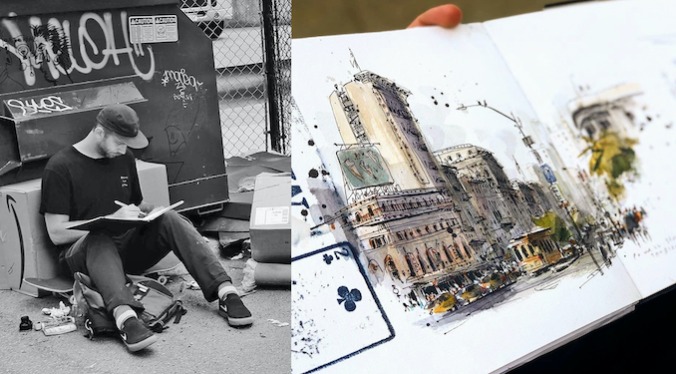

Photo courtesy of the artist. Design Features skateboards

A Venn diagram of artists and skateboarders would have a crowded intersection. From Ed Templeton’s iconic Toy Machine graphics to Tommy Guerrero’s lo-fi albums, contemporary art and skate culture are undoubtedly symbiotic. Netflix Production Designer Tomas Pajdlhauser recently sat down to talk about the lines that connect animation and skateboarding.

What came first for you, skateboarding or art?

I was introduced to art through skateboarding. A lot of my friends and the people I looked up to in skateboarding were artists. There was a big graffiti movement in the ‘90s in Canada that was really influential and many of those artists made skate graphics. I guess art and skateboarding were more closely linked in the ‘90s so it just seemed natural to be into art if you skated back then.

You started your animation career in background and environment design? Do you think your interest in urban space stems from skateboarding?

The reason I gravitated to backgrounds was definitely because of my interest in overlooked and underappreciated urban spaces. Skateboarding gave me a good internal library for how people use and connect to space. I also learned how urban spaces work through skateboarding. Understanding how a rail connects to stairs and being able to visualize the height of a sidewalk comes in handy when you’re designing fictional spaces.

You own Birling, a much-loved skateshop and café in Ottawa, and design all the shop’s board graphics. What makes a good board graphic? How does composing for animation differ from illustrating board graphics?

A good skateboard graphic is entirely subjective—the range of what appeals to people is infinite. Personally, I think it’s important to consider the shape of the board and how light and shadow move across it. I also like to think about how the graphic will look as it gets destroyed, since that’s what will inevitably happen. I use negative space to design in a way that will be most appealing after a few hours of use.

I also like to produce graphics that tell a story about the urban landscape where the board will likely be used. For example, Birling teamed up with the Bytown Museum in Ottawa to learn the histories of the local spots we skate. My favorite was a very famous Ottawa spot called “Big 2” underneath the – bridge. We grew up skating there and never thought about the history, but we found out that it was the site where archaeologists recovered the earliest evidence of an architectural structure in Ottawa—a blacksmith’s shop that produced tools for the workers who built the last stretch of the Rideau Canal. The graphic kinda drew itself from there…

Animation is not much different. The same way I compose a graphic on a board to account for the shape and placement of the wheels and how it gets used, in animation we stage and compose scenes to guide the audience through a shot. We make sure they know where to look and how to feel at that moment in time. Design is relative but what connects all design is the ability to predict and control the relationship between the product and its user/audience.

We saw your work as the designer on Red Bull’s Steady Pushing miniseries about Canadian skate scenes. What was it like working with Red Bull?

Working with Red Bull was great. I worked with legendary Canadian skate photographer Dan Mathieu as director and TJ Rogers as host to do what I do best: connect the urban landscape to skateboarding through animation. Each animation introduced the next location by telling a story about a Canadian city and I was able to lean into my ink and watercolor style. It was kinda the perfect project for me. Can’t wait for season two!

You’ve also done work designing for independent features. What’s the difference between working for small studios and giants like Netflix and Red Bull?

There are pros and cons to both. Smaller independent projects have less eyes on them and so the vision is more concise and clear. The relationship between production designer and director(s) is intimate, but you’re also usually dealing with fast turnaround and low budgets so there’s more pressure.

On the other hand, bigger theatrical features at studios like Netflix have much healthier budgets and longer schedules so there’s more time to hone the look and feel of the film. But, as a result, there are a lot more eyes on the project and voices that need to be heard. There’s always a risk of diluting the vision. It’s my job to know when to push back and fight for an idea so that the project doesn’t become too generic, and when to compromise to serve the smooth development of the product.

Before we let you go, what other ways would you compare animation and skateboarding?

Animation requires creating characters and spaces that are often fantastical, but they also need be believable. To do that successfully, you need real-world experience. There’s no better way to observe the world than on a skateboard, where you notice every crack in the sidewalk, avoid potholes, intuit the flow of traffic.

I also skated at a competitive level when I was younger—I did a lot of competitions and was in magazines and so on. At that level there’s also an interesting comparison with the pressure cooker of working on an animated film. I think the cliché that skaters are comfortable with failure is true. You fall a lot before you land a trick. During the design process, there’s a lot of trial and error as you figure out what the scene needs. You make a lot of bad drawings before you land on a good one.

The Paste editorial staff was not involved in the creation of this content.