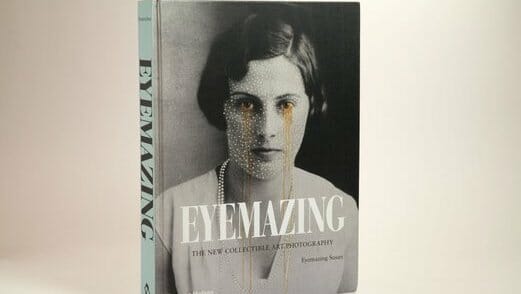

Eyemazing: The New Collectible Photography, edited by Susan Zadeh

All there is to see

A smartly dressed woman eats alone at the dinner table, an empty place set beside her. Outside in the yard stands a ghostlike man, watching through the picture window. Her late father? Husband? Do we see another ghost seated at the table? A woman? The woman? A dream?

•

Jean-Claude Delalande calls his photographs, like “À table” [p. 177], “ordinary stories.” What’s real, what’s memory? What accounts for the immense sense of sadness, loss and regret emanating from his bourgeois tableaux?

Such photographs may show “ordinary stories,” but we live in interesting times: The aftermath of 9/11 and the Unending Wars. Global economic instability. Seismic upheavals in the social order. For the past 10 years the award-winning Dutch photomag Eyemazing has captured ordinary stories in extraordinary times, our zeitgeist, with an unerring eye for the strange, controversial and affecting images they reveal.

Established at the cutting edge of contemporary international art photography…and the love child of visionary founder, Eyemazing Susan (Susan Zadeh)…Eyemazing arrives quarterly as a high-quality, large-format magazine, a collectible item of itself. Eyemazing celebrates its decade anniversary with this colossal collection featuring 130 photographers whose cutting-edge work pops from the pages. Eyemazing Susan draws upon a trove of works by emerging artists discovered and championed through the magazine, as well as brand names like Michael Ackerman, Sally Mann and Bettina Rheims. This 500-plus page compendium unquestionably gathers the very best in contemporary art photography.

With a project of this scope, finding unifying themes among thousands of photos presents a challenge. “The structure of the book was arrived at by physically removing the images from back issues of the magazine,” Karl E. Johnson explains in the book’s introduction. With artists’ names removed from the shots to preserve anonymity, “the freely intermingling images that had accumulated on the floor pointed to themes that made themselves known without having to be consciously ‘chosen.’”

Images fell into two broad thematic sections: “Dreams and Memories of a Past Life” evokes the role of dreams and memory in our experience of the real. “Our Body, Our Cage. Our Body, Our Home.” presents the human body as a holy vessel of sensual beauty and ultimate entrapment, at once empowering and disabling.

Myth, metaphor, dream and archetype thrive in contemporary art photography. Author and poet Steven Brown prefaces “Dreams and Memories” with a poetic essay pondering the camera’s claim to truth. Brown observes that the path of contemporary photography “was paved by the avant-garde dissenters such as Alfred Stieglitz’s Photo-Secessionists and later the more radical departures of Robert Rauschenberg, [though] now more than ever photographers use craft as a starting point to mine the human psyche for the Ding an sich [thing itself] rather than the thing outside the self.”

“The Milkmaid,” the iconic Vermeer still-life of a young maidservant pouring milk into an earthenware bowl, gets a treatment from Paul Kilsby in his shot, “The Maidservant” [p. 183].

In the Vermeer original, the sharply rendered painting focuses from foreground to background, just as the human eye would experience the scene. Kilsby often works by photographing and printing small-scale scenarios that seamlessly blend fragments of 17th-century paintings with real objects. He uses this technique to turn the Vermeer on its ear, sharply focusing on the finely detailed bread and table in the foreground, blurring the ostensible focal point of the painting, the pouring milk, just as a wide-open camera lens might do. Vermeer, we know, used a camera obscura as an aid to his process. Kilsby uses his own camera, “to investigate Vermeer’s paintings in the light of his own choice to mediate the world through the lens of a camera,” playing with focus, composition and luminosity while paying tribute to the Master.

John Wood, photo historian and poet, penned the essay introducing “Our Body, Our Cage. Our Body, Our Home.” The prose shines with insights into the nature of the human body—especially the nude—as presented in contemporary photography. “A great and serious photograph sets the photographed moment apart from all other moments. Why else capture it? Much of contemporary photography is boring because it does not do this. It captures moments that are exactly like all other moments, and so it never arises above the level of banality, the banality of most of life’s moments.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-