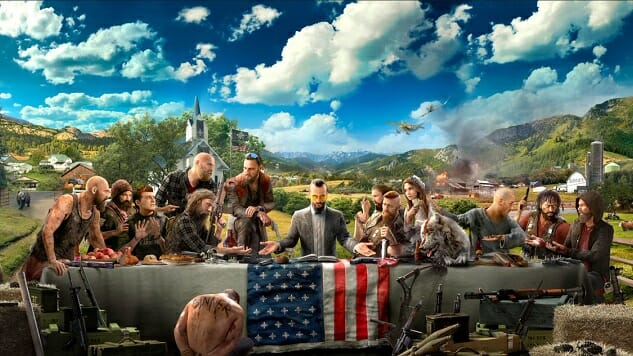

At least the Far Cry games are consistent. With Far Cry 5 the series once again uses a politically fraught backdrop to create a veneer of depth and intelligence that it never earns. Its commentary and engagement don’t extend past reminding us of various real life problems and then using them as fodder for shootouts and explosions. It’s the political equivalent of reference comedy, a Family Guy that’s read a newspaper or two, welded to the violence of a Rambo movie.

Set in rural Montana, in a small farming community overrun by a vaguely Christian cult with the military power of a small nation, Far Cry 5 evokes many of the tensions that have made this such a politically fractious time in America, including separatism, religious extremism, anti-government paranoia, and, simply by dint of its focus on gunplay, the ongoing gun control debate. It’s recognizable as the world we live in today, the one where political enemies no longer acknowledge the same set of facts and which was created in part by the rise of partisan right-wing media in the ‘90s (think talk radio and Fox News), but in a cartoonish prepper’s paradise where everybody’s a crack marksman and a survivalist with a fully stocked underground bunker. The game was in development before Trump was elected, but it obliquely refers to him a few times, and it’s clearly meant to take place in the America that would elect a person like that.

It’s all just set dressing, though. Far Cry 5 doesn’t attempt to establish any kind of cohesive political viewpoint. It has no convictions and no courage, other than saying single-minded death cults are bad, so feel free to single-mindedly kill them in great numbers for fun and entertainment. False prophet Joseph Seed and his Project at Eden’s Gate cult could have any backstory, and there could be any rationale for Seed’s melodramatic speeches, because, despite the surface-level relevance, none of it actually means anything.

Here’s an example of its lack of conviction. Seed and his cult are evil, the game says, because they forcibly convert people to their cult through violence. The game avoids making them explicitly Christian—their symbol isn’t a traditional cross, and when they reference a higher power they use the nonspecific word God instead of Jesus—but they’re clearly meant to be read as an extremist take on evangelical Christianity. Throughout history Christianity has used the threat of violence to convert others, and the game’s constant talk of sin, confession and repentance is clearly in the Judeo-Christian tradition. Almost immediately the game tries to soothe the concerns of anybody who might be offended by that, though, by introducing an explicitly Christian preacher who becomes one of your closest allies in the fight against Seed. Of course that preacher has no problem shooting people in the head if he feels like he has to. The violence of one self-proclaimed religious leader is portrayed as evil and hypocritical, while the violence of another is treated as a necessary triumph. Contrasting the prejudiced and hateful Christianity of Seed with a more mainstream alternative could have injected some nuance into the game’s depiction of religion, but instead it’s black and white—one is evil, one is good. The game wants you to think it’s saying something about religion, but then goes out of its way to present an acceptable alternative form of Christianity (that still revels in murderous violence) in order to head off any complaints about its depiction of the religious.

It also goes out of its way to avoid the racial connotations of the game’s concept. Seed’s following is racially diverse. This extremist militia wants to set up its own theocracy within Montana, but it doesn’t have the white nationalist sensibilities found in many real life militias and separatist movements. It’s understandable that a series that was rightly pilloried for the racism of Far Cry 3 would want to avoid something so delicate, but it’s just another example of how the game doesn’t want to seriously engage with the politics that it dredges up.

This approach feels especially feckless in the wake of a game like Mafia III. Not only did that game have no qualms with depicting the racism that its characters had to live with, but it made it a crucial part of its story. There’s even a mission where you can go shoot up an ersatz Klan rally. Mafia III openly attacked something that nobody in 2018 should be defending—white supremacy—while Far Cry 5 wants to seem daring while still keeping a pointed distance from anything that could be seen as too political or controversial.

Again, this isn’t unexpected. A cursory, noncommittal stance on politics has been a crucial part of Far Cry since at least Far Cry 3. After the powerful nihilism of Far Cry 2 the series cynically embraced a shallow approach that flirts with controversial issues in ways that are sensational but vague enough to hopefully avoid actual controversy. It’s persisted into Far Cry 5, and proves that consistency isn’t always a virtue.

Garrett Martin edits Paste

’s comedy and games sections. He’s on Twitter @grmartin.