Little Eve: A Deliciously Dark Period Tale About Family, Belief, and Trauma

Here in the heart of spooky season, it seems important to say: If you’re a fan of horror stories of any stripe and you’re somehow not reading Catriona Ward, please fix your life immediately.

A master at crafting smart, twisty, and downright disturbing stories that are both psychologically rich and deeply emotional, Ward’s fiction often eschews many of the familiar tropes and tricks most frequently associated with the horror genre. Yet, her stories are still impossible to look away from, and the kind of propulsive reads that mean you’ll probably stay up well past your bedtime just to find out what happens next. (Guilty as charged, is all I’m saying.)

Little Eve was originally published in the U.K. in 2018, where it went on to win the Shirley Jackson Award for Best Novel. That it (finally!) arrives in America following the success of Ward’s other (excellent) recent efforts, The Last House on Needless Street and Sundial, not only allows U.S. readers the chance to delve into the work that initially made her a name to watch in the world of horror fiction but to fully appreciate her remarkable range as an author.

A Gothic period piece told across two timelines, the book explores similar themes to her other novels—family, trauma, and questions of science versus faith—but manages to still somehow feel like nothing we’ve read from her before. Ward is a fantastic storyteller, and perhaps there is no better canvas for her skills than a story about how stories are made and the ways that snippets of truth ultimately form the basis for terrifying legends.

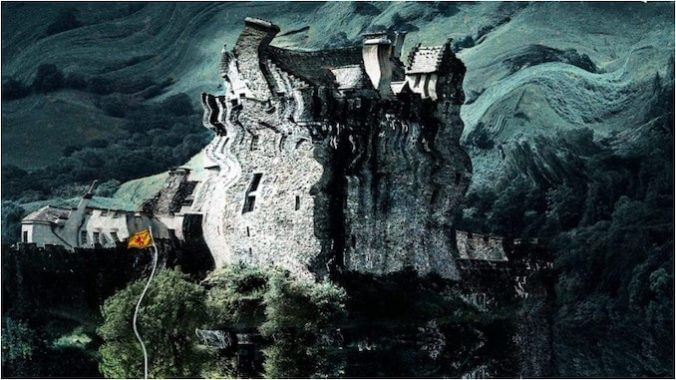

Set in a perfectly gloomy seaside corner of rural Scotland, the events of Little Eve jump between various years from 1917 to 1945 to retell the story of a brutal series of murders in the ruins of a castle known as Altnaharra. When local butcher Jamie MacRaith arrives at the half-ruined keep in January 1921 to deliver a slab of beef for Hogmanay, he discovers almost half a dozen dead bodies laid out in a disturbing formation around a group of standing stones, each missing an eye.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-