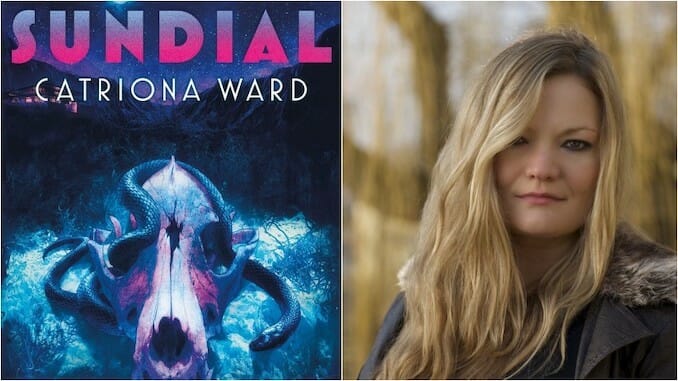

Catriona Ward on the Unique Female-Focused Horror of Sundial

Photo: Robert Hollingworth

Catriona Ward is not your typical horror author.

In a genre that can often seem full to bursting with blood and gore, detailed descriptions of violent deaths, and literal monsters lurking in dark corners, her books have a distinctly more psychological bent, telling stories that are frequently as heartbreaking as they are disturbing. But the author herself isn’t much a fan of the genre as a consumer.

“I am a complete scaredy-cat,” Ward admits with a laugh. “I cannot watch horror films and I find horror really difficult to read. But I think that’s the only reason I can write it—because if I’m not afraid I don’t really know how you’d expect the reader to be afraid.”

Ward’s fiction is notable for its dark and often uncomfortable psychological themes, though her stories include very few of the tropes and tricks most frequently associated with the horror genre and generally delight in turning expectations about what these stories should do and be on their heads.

“The things that really frighten me are more existential things, the things that go to the heart of and threaten or question human nature,” Ward explains. “I find those the more horrifying questions. And I always think perhaps we’ve [evolved] over thousands of years of myth-making and storytelling to ascribe acts and feelings to these supernatural tales or monster- or creature-based things that we can’t bear to accept perhaps might have human origins.”

Such is the case in Ward’s latest novel,Sundial. Part family drama, part psychological exploration, and part mystery thriller, the story follows Rob, a woman who initially seems like a typical suburban housewife. She’s got a husband and two daughters and if she had the sort of uncomfortable youth one doesn’t like to talk about in polite society, well, who can blame her. After all, her childhood home, Sundial, keeps many uncomfortable secrets, ranging from the awkward (her adoptive parents’ hippie off-the-grid style of living) to the downright disturbing (the bizarre family science experiments that involved overt animal abuse).

But when Rob’s eldest daughter Callie—a strange child who collects animal bones and whispers to imaginary friends no one else can see—starts exhibiting some disturbing and even potentially threatening behavior, she decides the only way to protect her perfect life is to take Callie back to where it all started, to where their family’s history of darkness ostensibly came from. Back to Sundial, where Rob will have to make a terrible choice.

Much like Ward’s previous novel, The Last House on Needless Street, Sundial is a story about assumptions—about whose word we trust, what stereotypes we accept, what kind of story we think we’re reading—and how those assumptions are occasionally used against us. The book covers a lot of similar ground, involving everything from narrators of questionable reliability and complex, unconventional familial relationships to the lingering ways trauma can often be passed down from one generation to the next.

But this book is also something else entirely: A twisty, intergenerational mystery that has one foot firmly planted in the past, Sundial wrestles with existential questions of human nature and why we are the way we are. And its most frightening moments are often entirely cerebral ones.

“I wanted it to be different,” she says. “I was really keen that it be distinct and have its own complete imaginative world. Needless Street, I think, was more about containment, Sundial it’s got that desert expanse to it.”

Yet, according to Ward, the very openness promised by the desert setting is, in its way, another well-told lie.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-