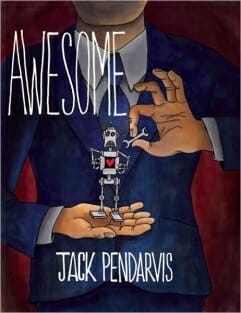

Jack Pendarvis

Mythical giant vs. the modern world—readers win

Moby-Dick has a white whale. Gravity’s Rainbow has outsized sexual shenanigans. Awesome, by Jack Pendarvis, has both.

The hero of this short, dizzying comic novel is the title character, a massive, handsome, supremely powerful man who strides the earth like nobody’s business. He wears a derby hat. He lives with his robot ward Jimmy, who is Robin to his Batman, and he has a kind of love affair with his downstairs neighbor, Glorious Jones. After his plans to marry her go haywire, Awesome is launched into a series of adventures that find him careering from odd situation to odd situation, applying himself gigantically wherever ?he goes.

Awesome is a huge man with many tiny problems, and this makes him unreal in many senses and all too real in others. The world he moves through resembles him in that regard: It is flecked all along the way with bits of everyone from Elkin to Twain to Mary Shelley, but is indebted mainly to American tall tales like Pecos Bill and Paul Bunyan.

Throughout, Pendarvis is funny. It is one of his defining characteristics, and no one will ever dispute it. He is funny the way Awesome is large. But there is a style in service of this characteristic, a mix of slippery diction and protracted conceits.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-