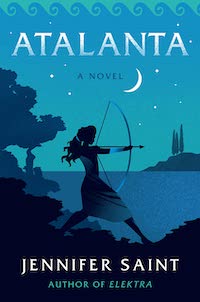

Jennifer Saint’s Atalanta Gives A Lesser Known Greek Heroine Her Due

Although feminist mythological retellings are all the rage in the world of publishing right now, many of them tend to touch on similar themes and stories, often even using the same characters. This isn’t a bad thing, necessarily—and I will happily read as many versions of Circe and Clytemnestra as authors want to put in front of me—but it does leave a space for more stories that aren’t, say, about the Trojan War. This is part of the reason why author Jennifer Saint’s latest novel, Atalanta, feels like such a breath of fresh air.

The story of the famous female warrior who journeyed with Jason and his Argonauts on their quest to find the Golden Fleece, Atalanta seems set to introduce an entirely new generation of readers to a woman who’s never really been given her due, historically speaking. Where Saint’s previous novel, Elektra, was a story about female rage—the tale of three very different women who are equally furious about the ways they’re denied the chance to have agency or voices of their own—Atlanta is a tale about legacy and memory, and the ways that women and women’s successes are often erased and marginalized, even in their own stories.

Left to die on a mountainside as an infant by her father, a Greek king who never wanted a daughter, Atalanta is rescued by a bear and raised by the goddess Artemis, who trains her to be a confident and capable warrior and to disdain the company of men. But when word of Jason’s plan to gather the greatest heroes of Greece to join his search for the Golden Fleece, Artemis sends Atalanta as her champion with the aim of winning glory in her name. Determined to prove her worth and skill, Atlanta endures the rudeness and skepticism of her male companions, who include such notables as Heracles, Castor, Polydeuces, and Euphemus. Though she makes a few friends—a surprisingly open-minded king’s son named Meleager and the legendary musician Orpheus—she’s frustrated by the fact that much of the trip’s supposed glory seems to arrive more tarnished than she was initially promised.

And, despite her obvious skill, particularly with a bow, most of the Argonauts seem determined to diminish and dismiss her, from outright ignoring her to eagerly claiming credit that rightfully belongs to her. This behavior generally reflects the consistent way her very presence is erased from many of the stories of Jason’s voyage—after all, how could a woman be seen as an equal with the world’s greatest warriors, or be the sort of hero that the poets will sing of forever? Wasn’t she always destined to be treated as an afterthought, no matter what she did?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-