Jennifer Saint’s Elektra Gives the Angry Women of Ancient History a Voice

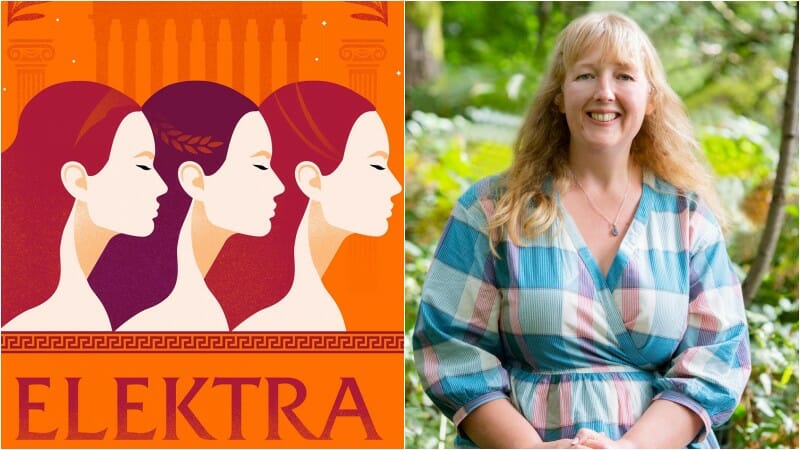

Photo: Katie Byram Photography

One of the most thrilling trends in publishing in recent years has been the rise of the female-focused mythological retelling, books that reevaluate and reassess some of Western literature’s most famous tales through a distinctly female lens and putting the spotlight squarely on the women who are often left to languish in the margins of men’s stories.

From Madeline Miller’s Circe and Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls to Natalie Hynes’ A Thousand Ships and Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad, female authors are spinning heartbreaking and haunting tales about these female characters and telling their stories from fresh perspectives. I know I’m not the only reader who can’t get enough of this particular vein of book, but there’s just something so poignant and necessary about these stories and the way they acknowledge the women that history has done its level best to forget.

Elektra, Jennifer Saint’s follow up to her (also very good!) novel Ariadne, reframes the Trojan War as a specifically female story by grounding it in the distinct perspectives of three different but equally furious women: Clytemnestra, wife of Greek king Agamemnon who sacrifices their daughter on the altar of his own glory; Cassandra, the unheeded prophetess who can see the future but not stop it from coming to pass; and the titular Elektra, who comes of age over the course of the decade it takes Troy to fall.

On paper, the three women have little in common (despite one being the daughter of another), but in Saint’s retelling, their lives intersect and intertwine in thematically rich ways, as each tries to forge her own path in a world in which women are often denied the chance to have agency or voices of their own. These heroines rage at the dying of the light, refusing to go quietly into the fates that male authors like Euripides, Homer, and Aeschylus have set out for them, and though their endings remain as inevitable as always, for readers, the experience is a deeply cathartic one.

We got the chance to chat with Saint herself about her latest novel, why she felt she had to tell these women’s stories, the important female perspectives that often get left out of Greek myths, and lots more. (We even get to hear a little bit about her next mythological retelling—that bit’s at the very bottom, if you want to jump ahead.)

![]()

Paste: I loved both Elektra and your previous novel Ariadne as well. What makes you want to put a new spin on these very famous myths? Do you feel like the story of these women are similar to or complement each other in some way?

Jennifer Saint: With both Elektra and Ariadne, I felt that their stories were overshadowed by those of the men in their lives. I had seen Ariadne’s story told through the lens of Theseus’ adventures so many times and how she recedes into the background, consigned to being a footnote to his legend even though he could only succeed through her courage and cleverness.

Elektra is more prominent, the titular subject of tragedies by Sophocles and Euripides, but I felt that there was still a huge void in her story—she comes into these plays as an adult woman whose powerful feelings of rage and vengeance are already fully formed and joins forces with her brother to take action. I wanted to go back and to trace the development of her anger and delve into the loss and trauma that shaped her that way.

In particular, I wanted more of her relationship with her mother who by then had become the focus of Elektra’s bitterness. I felt the same with Ariadne and Phaedra – I wanted to see these women in the context of their female relationships as well, to understand better who they were separately to their male counterparts.

Paste: Where did the idea for this retelling of Elektra come from?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-