Emotionally intricate and exquisitely crafted, Unaccustomed Earth’s descriptions of love and conflict are rendered through the lives of people whose traditions include arranged marriages and cultural cohesion. Much of the older generation seeks to honor tradition, and the younger seeks to explore personal choices.

“Only Goodness” poignantly deals with such choices, as an exceedingly successful daughter struggles with guilt over her role in her younger brother’s personal failures. Lahiri’s masterful unspooling of time allows us to freshly experience the characters’ hopes and their dread.

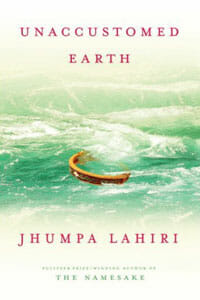

The longer form of this collection straddles those of Lahiri’s first two books, the Pulitzer Prize-winning short-story collection Interpreter of Maladies and the acclaimed novel The Namesake. In some ways, it mirrors the predicament of her characters—Indian Americans who, as in the previous works, straddle cultures. In essence, the stories compare the lives of young, American-reared Indians to the lives of their parents who immigrated to America, parents who have worked hard to establish family security, holding on to Indian traditions as they try to make their offspring successful American citizens.

The source of the book’s title is its epigraph, from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Custom-House, which ruminates on the good to be gained from a family’s diaspora. It reads in part, “My children have had other birthplaces, and, so far as their fortunes may be within my control, shall strike their roots into unaccustomed earth.”

Indeed, the title story concerns an adult daughter and her widowed father who find themselves in unfamiliar territory. The daughter, Ruma—after being well educated and earning a six-figure income as an attorney—has become a stay-at-home mom to her preschool-age son as she awaits the birth of her second child. Having moved from Brooklyn to Seattle, where her American husband has a new job, she considers whether to ask her father—visiting from his new one-bedroom place in Pennsylvania—to move in with her family, as would be traditionally expected of her.

Having never been very close to him—never even alone with him because of his role as bread-winner and her mother’s constant presence—Ruma fears catering to him as her traditional mother did. Shifting from the daughter’s perspective to the father’s, the story flashes back in time through memory exploring the disparate and overlapping emotions of these two characters. Sections of a puzzle slowly fit together to reveal the layered realities of father and daughter.

One reality is that, for the father, Ruma “resembled his wife so strongly that he could not bear to look at her directly.” Another is that, despite Ruma’s reluctance to care for her father, she finds herself living her mother’s life, tending to children and home while her husband travels for work. Meanwhile, her father—a self-sufficient world traveler since the death of his wife—has a girlfriend he’s reluctant to reveal. And he encourages Ruma to reconsider giving up the career for which she has worked so hard. Ultimately, the story is about change, showing that as younger generations advance into their adult lives and culturally diverse futures, older generations slip away, either in death or into ways of life parenthood kept from them. This, too, is unaccustomed earth.

In “Hell-Heaven,” the book’s second and shortest story, a young girl observes her mother’s friendship with a Bengali grad student who is new to Cambridge, Mass., and happy to meet a Bengali family so far from Calcutta. Clearly but chastely attracted to Pranab Chakraborty, Usha’s mother cares for him like a wife—she’s happy when he visits (cooking and primping for him), and sulks when he’s away. While the girl’s father somberly pursues his own research, the mother, daughter and Pranab entertain each other until Pranab falls in love and marries Deborah, an American student.

When Deborah invites Usha to stay longer at the wedding reception as her parents are ready to leave, her mother says no. (“As we drove home from the wedding, I told my mother for the first but not the last time in my life, that I hated her.”) One of Lahiri’s great strengths is to concentrate myriad conflicts into individual scenes like this, where cultural, romantic and family betrayal coalesce.

Stories of star-crossed lovers are not new, but when handled by Lahiri in the book’s second section, “Hema and Kaushik” becomes a nearly perfect example of the linked story form. Mostly epistolary, the stories are so richly detailed in their accounting of time, and so socially layered, that the meeting feels convincingly like destiny rather than contrivance.

In a reversal of a Jane Austen romance, the section ponders what could cause a well-educated, internationally aware Indian American woman to choose an arranged marriage to a man she cannot love. Like Austen, Lahiri is brilliant at describing ambivalent emotions, unleavened by humor. And the romantic novel’s standard is present: The story’s male object of desire is handsome, aloof and adventurous—a photojournalist documenting world horrors.

Almost all of Lahiri’s characters are driven by the pressure to succeed. Attending Harvard, MIT or the London School of Economics, hardly anyone is mediocre. And for all of their cultural awareness, the Indian characters seem inexplicably unaware of American ethnicities other than Caucasians. But these are interesting omissions, once again suggesting personal and cultural choices. As Lahiri’s Indian characters become more immersed in America, it seems they will attend to even more of its riches and sorrows.

John Holman is the author of Luminous Mysteries and Director of the creative-writing program at Georgia State University.