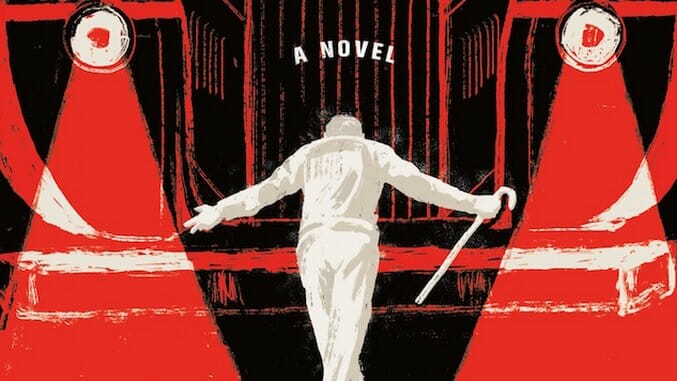

Paul Goldberg Delivers a Grimly Humorous Take on Soviet Russia in The Yid

Author photo by Gilles Frydman

At 56, Paul Goldberg can technically be framed as a debut novelist. Granted, he already has three nonfiction works to his credit, along with 30-plus years of reporting in the fields of oncology and healthcare as the editor of the award-winning publication The Cancer Letter. But the way Goldberg tells it, he’s never actually had a real job.

The Yid, meanwhile, is Goldberg’s first foray into fiction. Goldberg, who was born in Moscow and left for the U.S. at age 14, has created a charismatic team of unlikely heroes who become would-be assassins, uncovering a plot by Joseph Stalin to engineer his own version of the Holocaust in the U.S.S.R.

The Yid, meanwhile, is Goldberg’s first foray into fiction. Goldberg, who was born in Moscow and left for the U.S. at age 14, has created a charismatic team of unlikely heroes who become would-be assassins, uncovering a plot by Joseph Stalin to engineer his own version of the Holocaust in the U.S.S.R.

In Goldberg’s fast-paced action/comedy, February of 1953 is fading into March and uniformed ruffians begin making conspicuous midnight arrests of Jewish citizens around Moscow. A retired thespian and an aging surgeon—who are both former Red Army specialists—along with an expatriated African American engineer and a vengeful young woman fall into an unpredictable alliance. Each of them commit, for obvious reasons as well as their own, to unite and stop a second Holocaust.

With The Yid, Goldberg has found a graceful balance of gallows humor and film noir cloak-and-dagger suspense, as well as a mix between hard-boiled action and Shakespearean allusions. It took 10 years for Goldberg to get The Yid published, and while there’s a tacit encumbrance upon first-time novelists to make an impression, “I really didn’t care, honestly,” Goldberg says.

Publishers initially objected to his acerbic characters; they said readers wouldn’t be able to feel his characters’ pain. “I can’t help it,” Goldberg says. “I don’t write with a soul and happy prose. I can’t write ‘endearing,’ and gallows humor doesn’t strike people as something worth doing. That was a hard sell 10 years ago.”

But the world changed a lot in a decade. The Yid’s final draft changed slightly, too.

“I ended up grounding it more in the past with these characters when I rewrote it. But, really, if you were to do a textual analysis of the rejection letters I received 10 years ago versus the reviews I’m getting right now, there is absolutely no correlation. It’s like two completely different books. I didn’t make that huge amount of changes between the versions.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-