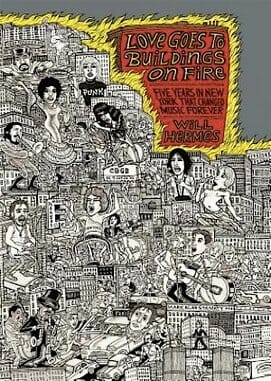

Love Goes to Buildings on Fire by Will Hermes

Rock ’n’ Roll will never die. But it may grow nostalgic …

In America, we love electric guitars, and the dominant music for more than a half century has been guitar-driven rock ’n’ roll. A pastiche of African American blues, jazz, country, and gospel music, rock ’n’ roll distilled the rebellious energy beneath the conformist veneer of the post-WWII industrial age. As the nation changed, so did the music, fragmenting into a dozen genres, and eventually hundreds. Rock ’n’ roll touches every aspect of American culture. Worldwide, it’s an ambassador of what it means to be an American.

It’s no surprise that as this new artform emerged so did a parallel world of comment on the form. Rock criticism proliferated with rock ’n’ roll, and its practitioners vary in personality and writing style as wildly as rock musicians. Patti Smith’s recent memoir Just Kids takes a poetic, often soft-focus look at the author’s early years in New York with her onetime lover and dear friend, the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe. When Smith first started out, she wrote for the rock ’n’ roll mag Creem. Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain’s Please Kill Me offers oral history as fractured and confrontational as the punk rock it catalogues. Lester Bangs’s Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung compiles years of smart, funny rambles on everybody from jazz to post-punk. The contemporary inheritor of these earlier writers has got to be Chuck Klosterman, whose Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs opens with the dictionary definition of solipsism … and then proceeds to use the word “I” several thousand times.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-