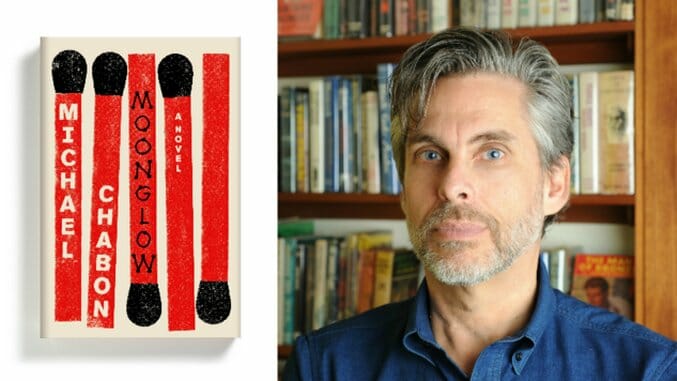

Model Rockets and Memoir: Michael Chabon Talks His Latest Novel, Moonglow

Author Photo by Benjamin Tice Smith

Moonglow, Michael Chabon’s new novel, finds its essence at the intersection between tiny moments of family history and the biggest global events of the 20th century. In weaving threads of his characters’ lives with threads of world history—the Holocaust, World War II, the Space Race—Chabon writes an enlightening book about humanity’s search for meaning.

Chabon’s imagination began churning with elements of his family’s past: conversations he had with his terminally ill grandfather more than 20 years ago; a great-uncle’s anecdote about getting fired from his job to make room on the payroll for Alger Hiss; and a mysterious 1950s advertisement for Chabon Scientific Co. model rockets. The result is that Moonglow unfolds as though it were a memoir, with the narrator listening to his grandfather’s life story. Throughout the text, Chabon draws subtle parallels between those intimate affairs and the internationally consequential events that occur almost in tandem.

“That point of tangency of the huge and the tiny was the initial thing for me,” he says in an interview with Paste. “The first impulse of this book was this family anecdote that I’d heard a couple times growing up, the intersection of this sad-sack, pathetic story of my great-uncle getting fired, with this huge arc of the Cold War and one of its most notorious figures. It popped into my head one day when I sat down to write something else. I found myself thinking of that anecdote, and that was my starting place.”

Chabon also knew that, on some level, he wanted Moonglow to be the history of a model rocket ad he discovered, carrying his family name but offering no further clues.

“That ad is real, and I have no explanation for it whatsoever,” he says. “So I decided to make one up. I coincided with the Space Race, more or less exactly, and was completely caught up with it as a kid.”

The model rockets, the Space Race, and the grandfather character’s World War II work as an intelligence officer all pointed Chabon in the direction of Wernher von Braun, the German aerospace engineer and inventor of the V-2 rocket who later immigrated to America. In much the same way that Chabon’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay uses Harry Houdini to introduce the central theme of escape, Chabon invokes a meditation on scientific discovery with von Braun, benefitting from an “At what cost?” hindsight.

“I remember my little kid’s view of Wernher von Braun, seeing him on Wonderful World of Disney, chatting about all these incredible orbiting space stations and colonies on mars and all these things we’d have when I grew up,” Chabon says. “That figure of von Braun was part of my imaginative landscape from a very young age, and then there was a gradual sense of disillusionment over the years, both with the ideals of the space program…and then the increasing consciousness of just how deeply von Braun was implicated in the Nazi slave labor structure.”

Chabon began writing about topics he’d taken an interest in his whole life, but as his continued research encountered some darker truths, that led to subtle shifts in his characters.