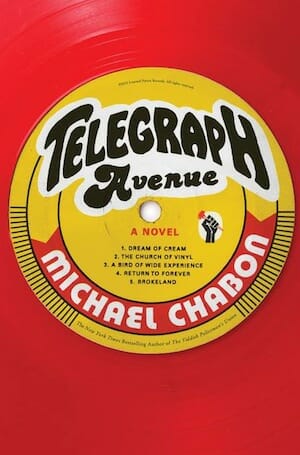

Telegraph Avenue by Michael Chabon

Style is often called upon to compensate for a lack of substance. In Michael Chabon’s Telegraph Avenue, style methodically drowns out substance with unrelenting, trivia-heavy riffs on music, a broad selection of quotes and scenes from a pair of fictitious blaxploitation films, admittedly amusing banter between characters and inventive yet painfully long descriptions of insignificant minutiae. Serious subjects course through this nearly 500-page novel, but they rarely congeal into solid themes.

The loosely structured (main) plot revolves around a business venture undertaken in 2004 by NFL star-turned-entrepreneur Gibson Goode, “president and chairman of Dogpile Recordings, Dogpile Films, head of the Goode Foundation, and the fifth richest black man in America.”

Goode wants to open a giant mall (a Dogpile “Thang”) on Telegraph Avenue in Oakland, Calif. Such a project would bankrupt several small, independent businesses nearby, including Brokeland Records—with its unparalleled jazz collection—owned and operated by Archy Stallings (black) and his best friend Nat Jaffe (Jewish). Goode’s endeavor frames the tale, coming into play at its beginning and end, Chabon choosing to fill the middle with a plethora of subplots. These mini-stories—one of which includes a cameo by then-Senator Barack Obama—prove entertaining and sometimes thought-provoking, but they also leave the book with an unfocused, meandering feel.

While he and Nat struggle to squeeze money out of vinyl in the early 21st century, Archy must also contend with other worries. His pregnant wife is angry over his infidelity and her troubles at work. His estranged father finds himself in trouble (again). And a son of whom he was only vaguely aware suddenly appears on the scene.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-