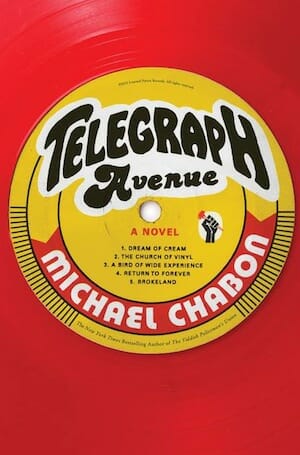

Telegraph Avenue by Michael Chabon

Style is often called upon to compensate for a lack of substance. In Michael Chabon’s Telegraph Avenue, style methodically drowns out substance with unrelenting, trivia-heavy riffs on music, a broad selection of quotes and scenes from a pair of fictitious blaxploitation films, admittedly amusing banter between characters and inventive yet painfully long descriptions of insignificant minutiae. Serious subjects course through this nearly 500-page novel, but they rarely congeal into solid themes.

The loosely structured (main) plot revolves around a business venture undertaken in 2004 by NFL star-turned-entrepreneur Gibson Goode, “president and chairman of Dogpile Recordings, Dogpile Films, head of the Goode Foundation, and the fifth richest black man in America.”

Goode wants to open a giant mall (a Dogpile “Thang”) on Telegraph Avenue in Oakland, Calif. Such a project would bankrupt several small, independent businesses nearby, including Brokeland Records—with its unparalleled jazz collection—owned and operated by Archy Stallings (black) and his best friend Nat Jaffe (Jewish). Goode’s endeavor frames the tale, coming into play at its beginning and end, Chabon choosing to fill the middle with a plethora of subplots. These mini-stories—one of which includes a cameo by then-Senator Barack Obama—prove entertaining and sometimes thought-provoking, but they also leave the book with an unfocused, meandering feel.

While he and Nat struggle to squeeze money out of vinyl in the early 21st century, Archy must also contend with other worries. His pregnant wife is angry over his infidelity and her troubles at work. His estranged father finds himself in trouble (again). And a son of whom he was only vaguely aware suddenly appears on the scene.

The subplots, though mostly linked to Archy, do not revolve around him, and they feature their own dynamics. Archy’s wife Gwen shares top billing with Nat’s spouse Aviva in their little saga, dealing largely with challenges they face as midwives facilitating home births. We meet Archy’s father Luther, star of long-forgotten blaxploitation and kung fu flicks, as an accomplice to a crime in an extended sequence set in 1973. Now, apparently trying to blackmail his former partner, a funeral home owner as well as a city councilman, Luther carries on a volatile relationship with old co-star and flame Valletta Moore.

Sections with Titus, Archy’s 14-year-old son, feature Titus’s friendship with Nat’s son Julie (Julius), who’s about the same age. Julie is almost certainly gay and smitten with Titus, but Titus leans strongly toward heterosexuality—though this does not interfere with his “accepting every last note and coin of Julie’s virginity.”

If all that plotting weren’t enough, Chabon spins in an important subplot on aging organ player Randall “Cochise” Jones, a father figure to Archy who seems to have given him and Nat the name for their store. “Mr. Jones was … as far as Archy knew, the first person to use the term Brokeland, to describe this neighborhood, the ragged faults where the urban plates of Berkeley and Oakland subducted.”

We find Chabon’s well-known flair for language (recall the Yiddish cadence and expressions in The Yiddish Policemen’s Union) on full display in Telegraph Avenue. In a risky move that the author pulls off with confidence, he renders much of the dialogue in a way that marks its speakers as urban African-Americans. The only quibble one might have? Chabon, in what may reflect a politically correct desire to balance coarseness with a measure of refinement—something he does not feel compelled to do with his white protagonists—lets characters flirt with grandiloquence. This can feel incongruent—except in the case of Chandler Flowers (the undertaker whom Archy’s father blackmails). Flowers’s pomposity is very much a part of his persona.