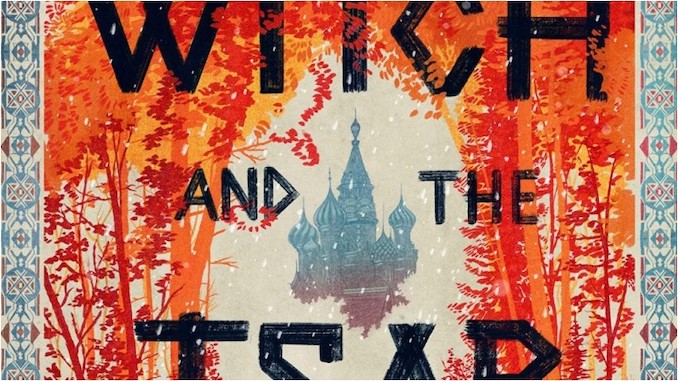

The Witch and the Tsar Is a Fantastical, Feminist Reimagining of Russian Folklore

Dozens of books have hit shelves over the past couple of years that aim to reevaluate and reframe the stories of some of the most vicious and villainous women in fiction, giving supposed monsters from Greek mythology, witches from Western fairytales, giants from Norse legends, and even queens from Indian epic poems the voices and perspectives that have long been denied to them. (Long may this continue, is what I’m saying—because it’s honestly producing some truly excellent stories.)

Debut author Olesya Salnikova Gilmore puts a uniquely Slavic spin on this trend with The Witch and the Tsar, a fierce, historically rich reimagining of the story of Baba Yaga, a figure that’s traditionally depicted as a deformed, physically repulsive old woman who may or may not steal and eat children. A witch who allegedly dwells in a magical forest hut that stands on chicken legs, she is known for her dangerous and often duplicitous or even demonic nature. Happily, that’s not the story that Gilmore is interested in telling.

The Witch and the Tsar follows the story of Yaga Mokoshevna, a half-human, half-immortal daughter of a goddess in 1560 Russia, whose dark reputation as a witch has earned her the nickname Baba Yaga the Bony Leg. After being kicked out of yet another village, Yaga has chosen to live alone and isolated in the forest along with her telepathic wolf and a vaguely sentient house called Little Hen. (Yes, it has chicken legs. No, the story sadly never really tells us where she came from. Like so much else that is magic in this world, Little Hen simply is, and that’s that.) Occasionally someone will be desperate enough for her aid that they’ll seek out her services in secret, under cover of darkness, but for the most part, she’s left alone.

But when the Tsaritsa Anastasia Romanovna Zakharyina-Yurieva comes looking for a cure for a mysterious illness, Yaga finds herself drawn back into the mortal world in an attempt to protect her friend from the threat of an unknown assassin and Russia itself from the worst qualities of her paranoid and vindictive husband. Embroiled in a world of political intrigue that involves both greedy boyars and manipulative gods, Yaga will ultimately be forced to fight to save the homeland she loves from enemies both human and supernatural who threaten violence and war.

-

-

-

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 3:10pm

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Urls By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:55pm

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-