Note: This piece can be found in Paste Quarterly #1, which you can purchase here, along with its accompanying vinyl Paste sampler.

In the late ‘60s, a discontent Jack Kirby thought long and hard about the industry he helped build. For the co-creator of Captain America, The Fantastic Four, The X-Men and countless other super properties, the arena of mutants, mayhem and escapism had lost its luster for The King of Comics.

“You fellas think of comics in terms of comic books, but you’re wrong,” Kirby told a crowd at a California convention. “I think you fellas should think of comics in terms of drugs, in terms of war, in terms of journalism, in terms of selling, in terms of business. And if you have a viewpoint on drugs, or if you have a viewpoint on war, or if you have a viewpoint on the economy, I think you can tell it more effectively in comics than you can in words. I think nobody is doing it. Comics is journalism. But now it’s restricted to soap opera.”

If only Kirby had been born a century earlier, he might have felt that the art of combining images and word balloons was less superficial. Long before the domination of companies like DC and Marvel, the comic strip and cartoon served as a vehicle of socio-political unrest and mediation. Even the arguable first comic/cartoon character—Richard Outcault’s 1895 creation, The Yellow Kid—tackled so much real-world friction that he inspired the term “yellow journalism.” German artist Thomas Nast used political cartoons to expose and oust corrupt politician William “Boss” Tweed from office, leading to his arrest in 1871. But the medium was even embraced by less-publicized voices to reflect the harrow and toil more commonly addressed in prose today.

Take Canadian Mountie William Scott, who fought in the Western Front of World War I. He spent his time in the muddy, shit-strewn trenches of France and Belgium waiting, fighting and drawing. He carried a turquoise sketchbook bound in fabric, marred and brittle from being soaked and dried countless times. He drew cartoons about soldiers, women, children; ruminations on the politics that had forced him into wartime chaos—and the domestic purity that waited for him, should he survive.

But Scott isn’t a name synonymous with turn-of-the-century political cartoons or the Golden Age of comics. To date, only two people alive have seen his work—my father and me. To the best of our knowledge, Scott never attempted to publish his comics, and his weathered sketchbook only fell into our hands for a very simple reason: my father and I, respectively, are Scott’s grandson and great-grandson. William Scott emigrated from Dumfries, Scotland, to Toronto, Canada, in 1907 where, as mentioned, he became a member of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, before serving in the infantry of the Canadian military during World War I. Public record of where he went and what he did is overwhelmingly vague and bureaucratic, relegated to the faded cursive on documents signed nearly 100 years ago. But what isn’t specifically stated can be connected by both historical touchstones and commentary within the notebook.

Canada declared war on Germany in August 1914. As World War I is often described as a global drunken bar fight, this was just another act of political obligation; at the time, Canada was a British dominion and its soldiers were devoted to the United Kingdom’s martial interests as soon as British Prime Minister H.H. Asquith swung his country’s proverbial pool cue at Germany and its attempts to seize France. Canadian forces were dispatched to the Western Front, where they engaged at—to name a few of the bigger events in chronological order—the Battle of Ypres (Belgium), the Beaumont Hamel (France), the devastating Battle of the Somme (France), the Battle of Vimy Ridge (France), the Battle of Passchendaele (Belgium) and the final Hundred Days Offensive in 1918 that ended the war. These events defined one of the most brutal and draining hellscapes of historical combat. World War I marked the first time technology including artillery, toxic gasses and tanks had been employed in battle, a massive demarcation from the romantic pageantry of horse cavalries and hand-to-hand combat witnessed during the Napoleonic Wars a century earlier. As Dan Carlin notes in his lauded Hardcore History podcast, WWI marked the first time when humanity had the tools to end humanity.

The Battle of Ypres, the Canadians’ first major battle, witnessed 6,000 Canadian soldiers killed, wounded or captured. Passchendaele claimed 16,000 alone. The Battle of the Somme has emerged as one of the wettest bloodbaths in the history of war—68,000 German and British-led soldiers died during the battle’s first day, wracking 1.2 million casualties overall. The Canadian War Museum cites that 61,000 people lost their lives and 172,000 were wounded over the course of the entire war—more than 37% of the total enlistees. From a macro perspective, approximately 17 million soldiers and civilians fell victim to World War I. This is all to say that the chances are precipitously high that William Scott—a member of the frontline infantry—saw and endured a parade of atrocities during his years of service. And when in the sodden, rat-strewn trenches, marching across landscapes leveled into fauna-less moonscapes, his outlet was to draw. And he drew a lot.

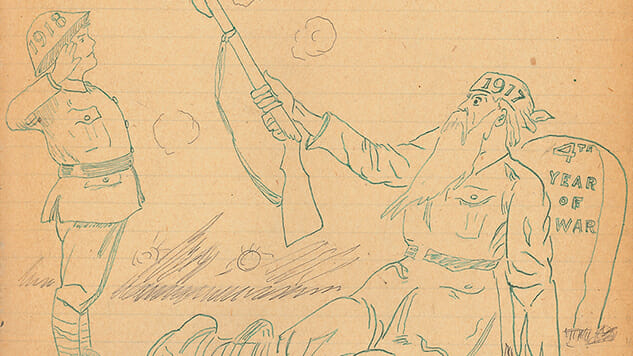

His notebook contains 69 sketches, rendered in a fluid, clean style with light hatching. The approach bears a passing resemblance to the aesthetic of cartooning pioneer Winsor McCay. But unlike McCay and his most notable contribution, Little Nemo in Slumberland, all of the cartoons are firmly grounded in reality. The opening illustration presents an ornamented title page with the text “1917,” held up by two Victorian children engulfed by roses and vines. (At the earliest, this would date the sketchbook to the Battle of Vimy Ridge.) Idealistic images of children, patriotic banners, one- and multi-panel comics, and toward the back, many women, occupy the majority of the book. One comic features infantrymen crouching at their camp as a shell whizzes by, another six-panel entry charts the turbulent romance of an army officer with an inamorata, the text doubling as a cooking recipe (“Take one Perfect Peach and one Ripe Nut/Mash and well mix together”). One of the most touching pieces portrays a child with a helmet marked “1918” saluting a bearded veteran with a headband labeled “1917.” He lies back against a tombstone engraved “4th Year of War.”

The most spectacular element of the art isn’t how polished or professional it is. It’s not. These pictures were created by a law enforcer and carpenter, not a seasoned illustrator. They’re the creation of a skilled hand, albeit one that wasn’t honed over years of practice. And this raises the question: was there a point when comics stopped being a universal form of expression for humanity’s spectrum of experience? Or, to re-quote Kirby—also a veteran whose time in World War II flavored many of his future designs—why aren’t we thinking of comics “in terms of drugs, in terms of war, in terms of journalism”?

Connecting today’s mainstream comic and cartooning market with journalistic nonfiction is a hard sell by any metric. Though successful cartoonists including Joe Sacco (Footnotes in Gaza), Sarah Glidden (Rolling Blackouts), Garry Trudeau (Doonesbury) and the team of Nate Powell, Congressman John Lewis and Andrew Aydin (March) have all used sequential art and cartoons to tackle war, politics and social discord, they’re the exception to the rule. Direct-market distributor Diamond didn’t cite one nonfiction or realistic fiction book in its top 500 single issues for 2015—all entries fell within the sci-fi, fantasy, horror and superhero genres. That trend may be changing, albeit slowly; as of December 2016, Amazon’s bestselling graphic novels list includes both compilations from Trudeau and the March team, as well as memoir comics from Sarah Andersen and Allie Brosh. Even if one refuses to condescend against comics’ near-absolute embrace of genre fiction and escapism, why isn’t the marriage of word and illustration used with the same potency it was 100 years ago? Why aren’t political cartoons ousting corrupt politicians like Boss Tweed, or addressing poverty and societal discord like Outcault’s smiling street scamp? Or, in my great-grandfather’s case, exploring the loneliness, violence and heroism of an event that thinned populations and redefined global politics? If my great-grandfather’s work means anything, these off-white pages reinforce one simple truth: Comics and cartoons are capable of communicating humanity in its rawest form.

Special thanks to Jenny Robb, Caitlin McGurk & Sean Howe.