Trash Market by Tadao Tsuge

Writer: Tadao Tsuge

Artist: Tadao Tsuge

Publisher: Drawn + Quarterly

Release Date: May 12, 2015

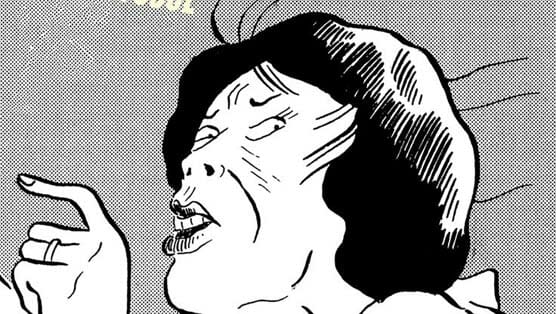

One of the strangest things about Trash Market, a collection of postwar Japanese manga by Tadao Tsuge, could be the cover choice. First, it shows an image from a panel in its flipped (original?) orientation, calling attention to the publisher’s decision to reorient the book to the Western left-to-right standard. Second, it features a woman in the act of yelling, “Everybody… There’s a rapist”—even as her thought bubble says “snicker….” The words, of course, don’t appear on the cover, but when one encounters the panel in the middle of “Gently Goes the Night,” it’s immediately recognizable and sends a shock through the system. All of this is to say that Trash Market is somewhat opaque as a work, even down to its details. Tsuge isn’t nearly as accessible an artist as Shigeru Mizuki, whose work D+Q also publishes. His drawing is sort of a mess. His stories are driven by emotion and impression rather than plot. But they’re very much of their era, and they do have elements that could earn a recommendation.

Trash Market collects six stories originally published between 1968 and 1972, mostly in Garo, an alternative manga magazine that also featured the work of Tsuge’s older brother Yoshiharu. Some of (Tadao) Tsuge’s autobiographical writings appear at the end of the book, and, combined with editor Ryan Holmberg’s essay, they tell us that some of the stories are autobiographical. The title story—which features a group of men hanging around a blood bank on a hot day, waiting to sell their fluids for cash while swapping fish stories—comes from Tsuge’s time working at just such an establishment. “Song of Showa,” in which a small boy struggles with an abusive home environment, set upon by both father and grandfather, likewise comes from the artist’s experiences. “Up on the Hilltop, Vincent Van Gogh” follows a night in the life of a young artist who traces the biography of his predecessor, and Holmberg says it, too, bears some resemblance to Tsuge’s life.

Trash Market collects six stories originally published between 1968 and 1972, mostly in Garo, an alternative manga magazine that also featured the work of Tsuge’s older brother Yoshiharu. Some of (Tadao) Tsuge’s autobiographical writings appear at the end of the book, and, combined with editor Ryan Holmberg’s essay, they tell us that some of the stories are autobiographical. The title story—which features a group of men hanging around a blood bank on a hot day, waiting to sell their fluids for cash while swapping fish stories—comes from Tsuge’s time working at just such an establishment. “Song of Showa,” in which a small boy struggles with an abusive home environment, set upon by both father and grandfather, likewise comes from the artist’s experiences. “Up on the Hilltop, Vincent Van Gogh” follows a night in the life of a young artist who traces the biography of his predecessor, and Holmberg says it, too, bears some resemblance to Tsuge’s life.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-