Bourbon Pricing Is Getting Out of Control, and Only the Consumers Can Stop It

Photo via Getty Images, John Sommers II, Buffalo Trace, Heaven Hill, Brown-Forman, Four Roses, Facebook Drink Features whiskey

It’s no shock, or particularly astute observation, to note the way that American whiskey prices have climbed in the last 15 years. The brown liquor revival brought along a boom period for the industry as a whole, and many of the largest and most popular American distilleries responded to this new wave of interest by embracing an increasingly premiumized model for their whiskey lineups. In addition to new product launches, older brands often received a new coat of paint … and higher price tags, to boot. Prices rose across the board—incrementally in most cases, and dramatically in others, as a new generation of whiskey drinkers discovered their love of bourbon, rye and more.

And for the most part, these increases were the understandable effects of basic economics. As demand began to boom in the back half of the 2000s, distilleries struggled to keep up on the supply front, as most had failed to fully anticipate the steadily growing interest in American bourbon in particular. Whiskey is a product with a long production and aging period, which means it can’t respond with alacrity to changes in the market, especially for well-aged examples. You’ve got a shortage of your 12-year-old bourbon brand? Well, I hope you laid down a bigger reserve of it 11 years ago, or there’s not much you can do about it in the near future, short of sourcing that whiskey from someone else.

These are natural factors that contributed to steadily rising manufacturer suggested retail prices (MSRPs) across the industry in recent years, and they should be considered a necessary downside for the consumer of seeing the category revitalized and greatly expanded. However, there’s also a powerful undercurrent to contemporary American whiskey pricing that is now threatening to totally redefine the idea of what any given bottle of bourbon is “supposed to” cost. We’re talking about the wild west that is whiskey pricing as set by retailers, and a runaway hype train of bourbon fanaticism that has increasingly driven consumers to pay secondary market prices for whiskey from primary market retailers. In the process, they’ve already shattered the idea of “MSRP” on numerous brands, and as time goes by, it’s only getting worse.

Or in other words: Are you ready to pay 300 or 400% mark-ups from MSRP at the local package store on some of your favorite bourbon brands? Because it’s happening all over the U.S. right now, and retailers are becoming more bold in their price gouging with every passing month. And as much as we’d love for the distilleries or distributors to somehow stop this from happening, the limitations of federal law means that the power to affect change rests almost entirely with us, the consumers.

This is all to say the following: Bourbon pricing is getting out of control, and only we can stop it. Allow us to explain in far more detail.

![]()

Fueling the Fires of Bourbon Hype

Before we can understand how retailers are able to get away with normalizing massive mark-ups from MSRP, we need to understand the basics of how the internet has built a self-sustaining bourbon hype cycle for certain distilleries and brands. Ultimately, it’s these communities that fuel the intense hype and desire for many bourbon brands, which leads to inflated secondary pricing and eventually inflated pricing at the neighborhood package store.

Put simply, there’s a mania that exists today for certain brands, and the breadth of that mania seems to be expanding all the time. A decade ago, for instance, you had likely heard about collectors going to great lengths to secure bottles of ultra sought-after brands such as Pappy Van Winkle, a premium wheated bourbon from Buffalo Trace Distillery. As Van Winkle became increasingly impossible to get, the collecting mania shifted to Buffalo Trace’s W.L. Weller lineup of wheated bourbons, touted by collectors as the “next best thing” to Pappy because they were made from the same mash bill. Quickly, the W.L. Weller brand, which had been a bottom-shelf staple for years, disappeared from shelves and became a hot item on the secondary market. And as Weller became harder to find, the mania shifted again, and again, and again, down the line, to the point that a frenzy built for seemingly every Buffalo Trace brand. Today, it can be very hard to find (depending where you are) almost any product the distillery produces, from Blanton’s and E.H. Taylor to Eagle Rare, Sazerac Rye, and even the flagship Buffalo Trace Bourbon. In fact, even the sub-premium, bottom shelf Buffalo Trace bourbon brand, McAfee’s Benchmark Bourbon, is receiving a line extension this year with five new variations, in new, premiumized labels such as “Benchmark Top Floor,” “Benchmark Small Batch” and “Benchmark Single Barrel.” To repeat: A bourbon that is routinely sold in 750 ml bottles for LESS THAN $10—we bought a bottle for a blind tasting for $8.49 only two years ago—is expanding its line and increasing its price point by at least 100%, into the $20-25 range, in order to take advantage of this distillery-wide hype.

If it’s a Buffalo Trace product of any kind, odds are good that package stores have started charging steep mark-ups on it.

If it’s a Buffalo Trace product of any kind, odds are good that package stores have started charging steep mark-ups on it.

This sort of hype trickle-down phenomenon affects products from many different distilleries, although the starting point of Buffalo Trace’s Pappy Van Winkle is hard to replicate in terms of the power it possesses to transform the hype level of any product even tangentially related to it in any way. As a result, Buffalo Trace has a tendency to command a lineup-wide level of hype that no other American distillery can touch, and it’s the online whiskey communities that reinforce this perception.

It’s Instagram, Reddit and especially Facebook where many of these associations have been formed in the mind of the consumer, and where you can often watch hype being fomented in real time. It’s a function of attention, groupthink and positive reinforcement—discussion in these communities constantly circles around just a small handful of brands, and posts that users make about those brands (often Buffalo Trace, or other limited releases) get more attention and engagement from users than posts about whiskeys that are readily available. As a result, posters are incentivized to focus on only that short list of hype-worthy brands, and new posters—there’s been an especially big influx of new people in the bourbon scene in the last couple years—absorb the lesson that it’s exclusively these brands that are worthy of their time. The tunnel vision that sets in here can ultimately poison entire forums for whiskey discussion, especially for the newbies, who leave convinced that only a handful of brands are “the good stuff” because that’s all they ever see anyone talk about. Every post from a new user becomes a query as to where they can find Blanton’s or W.L. Weller, and seemingly every other photo is someone excitedly boasting about their “score,” with a picture of a receipt where they paid 100-200% MSRP for a bottle of something that was easily accessible 5 or 10 years ago. People who are new to the space likewise end up believing that this is the way things have always been, rather than knowing how dangerously imbalanced the hype and gouging cycle has become.

One might expect that when a member of these groups posts a photo of their meticulously cleared off kitchen table, acting as a shrine for a dozen or two bottles of newly acquired and carefully arranged Buffalo Trace, W.L. Weller, E.H. Taylor and Blanton’s, the other community members might reply with the likes of “hey, leave some for the rest of us.” In reality, though, this is rarely what happens. Instead, these communities become self-sustaining hype machines, because each photo a guy posts of his “score” is met with adulation—a potent mixture of envy, praise, and backslapping for whoever managed to buy up an entire case of something like W.L Weller Antique 107, which is a common target. These posters are praised for their “hunting” and hoarding abilities, and that niche, celebrity-like status fuels the desire of the community’s observers to do the same, and subsequently justifies the DMs they’re shooting off to the original poster, who is no doubt fielding offers to sell a portion of his collection on the less-than-legal secondary market at a tidy profit. Everything about the nature of these Facebook pages perpetuates the hype cycle.

The typical content of any given “check out my score” Facebook post on whiskey hunting pages.

The typical content of any given “check out my score” Facebook post on whiskey hunting pages.

Even the media plays its own role in normalizing hype, and eventually price gouging. After Buffalo Trace’s E.H. Taylor Single Barrel Bourbon won a gold medal at the recent 2020 International Wine and Spirits Competition, Forbes wrote a piece noting that the whiskey, with an MSRP of $70, was “frankly still a bargain at $235.” There’s no doubt this is a quality bourbon, but if you’re asking us, that’s an irresponsible statement for a publication to make, and one that encourages bourbon neophytes to think 300% mark-ups are normal or acceptable. The “still a bargain” comment rightly received some criticism from other whiskey critics online, but this kind of thing is par for the course when it comes to how we write about hyped bourbon.

But that brings us to the meat of this piece, which is this: If everything around the consumer has convinced them that 300% MSRP is a reasonable price to pay for bourbon, what’s stopping the retailers from just charging whatever they think they can get away with? What’s stopping them from bringing secondary pricing to the primary? And as it turns out, the answer is “very little.”

![]()

The Primary Market Becomes the Secondary Market

Type the right brand names into Google, cruise over to the “shopping” tab, and get ready to be disgusted by the thought that people throughout the U.S. are currently tripping over themselves to spend the same amount on 6 or 8-year-old bottles of bourbon that many scotch or cognac collectors are shelling out for 20-year-old vintages. And they’re not paying those prices via less-than-legal transactions between buyers and collectors who double as “flippers”—they’re paying package stores more than you’d likely believe in order to snatch allocated or limited release bottles. Welcome to the post-MSRP experience, where package stores simply charge whatever they want for any given bottle of bourbon, and people are still desperate enough to pay it.

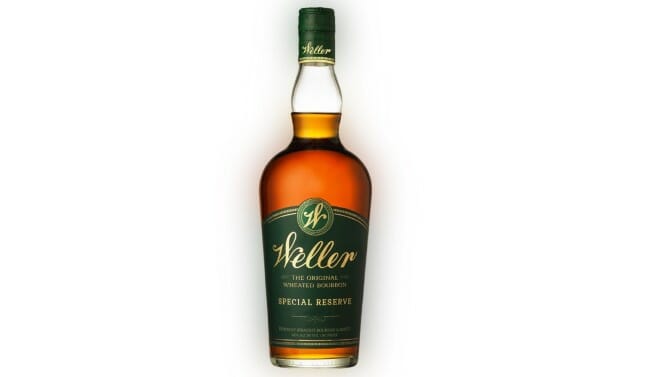

The most common targets for package store gouging are of course those sought-after Buffalo Trace brands, such as W.L. Weller. In order to illustrate the range of pricing you’ll come across, let’s quickly look at one brand in particular: The flagship W.L. Weller Special Reserve.

Five years ago, a common sight at $15-20. Today, package stores will try to charge you $100 for a bottle.

Five years ago, a common sight at $15-20. Today, package stores will try to charge you $100 for a bottle.

Weller Special Reserve, despite the fancy sounding name, is a formerly bottom shelf, non-age stated wheated bourbon that today has an MSRP around $25. It’s a relatively low-strength (90 proof) introduction to the Weller lineup of wheated bourbons, originally intended to be an affordable mixer or no-nonsense sipper, before the demand for Weller made it something that people chase delivery trucks to acquire. As recently as 5-10 years ago, it was not particularly sought after or difficult to find, with an MSRP closer to $15. Looking at package stores that conduct sales online, you can see just how much the asking price for a 750 ml bottle of W.L. Weller Special Reserve is capable of varying today:

— A mere $33 from Total Wine, in the rare moments the whiskey is in stock.

— $70 from this retailer, who marks it “down from $130!” in order to make it look like you’re getting a great deal.

What a discount! Such value!

What a discount! Such value!

— A nice, round $100 from this retailer, which is 400% the MSRP.

— $114 from this retailer, which feels like a not-at-all random number.

— $250, if you want to just go bulk and buy a 1.75 ml bottle instead. Somehow, this retailer is offering a worse deal per oz for the larger bottle, because of course they are.

These kinds of prices aren’t just cutthroat, either—they also manage to become deeply illogical, throwing the entire idea of a “product lineup” with scaling MSRPs out the window. For example, Old Weller Antique 107 is considered the next step up the Weller family tree, and as a result you’ll find many package stores inflating its price to around $200, which is roughly 400% MSRP. But at the same time, you’ll also find random outliers—here’s a place selling Old Weller Antique 107 for $80. Now you have the strange scenario where a product that is “supposed to” cost more is actually being sold for less than the price commanded by its little brother. Did these guys not get the memo on the correct gouging levels that everyone else had agreed to?

This kind of weird cognitive dissonance becomes common when package stores aren’t applying any kind of consistent logic to their pricing. In a reddit thread on r/bourbon, commenters discussed mark-ups on various Buffalo Trace products, and one commenter from NYC in particular highlights the absurdity of this situation when he writes the following:

“One store had regular Buffalo Trace for $54, right next to Eagle Rare for $40. Oddly, this store has Wild Turkey Rare Breed for $47, the lowest local price. A nearby competitor that usually has fair prices just put out a single bottle of Weller SR for $80 and a single bottle of Blantons for $90, IIRC. E.H. Taylor SB (Small Batch) was still $52. Buffalo Trace was $37, and Eagle Rare was $42.”

Suffice to say, this kind of inconsistency obscures which products are even intended to cost more in terms of the MSRPs initially set by the distillery. A package store selling Buffalo Trace Bourbon for more than Eagle Rare makes zero sense, given that they’re produced by the same distillery, from the same mash bill, but Eagle Rare has the higher age statement and higher MSRP. It is supposed to be the more premium product, but when bourbon pricing goes off the rails, these price tags begin to defy logic. The same goes for bottles of W.L. Weller Special Reserve, with their $20 MSRP, somehow being priced higher than E.H. Taylor Small Batch, which has more than double the MSRP. There’s no rationale for this that makes sense.

And it’s not just the Buffalo Trace products, either, much as it may seem like it during a cursory examination. As time goes by, the practice of gouging on anything that generates a certain level of hype is becoming increasingly standardized. That means 300-500% mark-ups from MSRP from package stores on desired bottles such as Old Forester Birthday Bourbon (Brown-Forman), Old Fitzgerald Bottled-in-Bond (Heaven Hill), Michter’s Toasted Barrel and Four Roses Small Batch Limited Edition. Or in other words, it’s not just trickle-down from Pappy Van Winkle—anything that now generates the slightest bit of hype or excitement, or is a limited release, is fair game for retailer gouging in any state that doesn’t have state-controlled liquor stores. Those systems, while far from perfect, remain bastions where bottles of these products are still sold at MSRP, although that arguably makes them even harder to acquire.

Other bourbon limited releases are also likely to see huge mark-ups from retailers these days.

Other bourbon limited releases are also likely to see huge mark-ups from retailers these days.

This gouging phenomenon and the online hysteria surrounding certain brands is something that other whiskey industry observers have of course witnessed unfolding across Facebook and their own local whiskey communities … or even in the aisles of package stores. I spoke with two such whiskey industry observers: Jason Callori, a popular YouTube whiskey reviewer and host of The Mash and Drum, a channel with more than 24,000 subscribers, and Fred Minnick, one of the whiskey industry’s best known writers and critics. Said Minnick, when we began our phone conversation: “I think you’re writing about this at a good time.”

“The secondary market could best be thought of as living, breathing data,” said the Louisville-based Minnick, who has authored numerous bourbon books and hosts an influential whiskey podcast. “That’s where you see the real demand right before your eyes. So it did become sort of laughable to see SRPs coming out in more recent years and they’re nowhere near what people are paying on the secondary market. Ultimately, the retailers, distributors and distillers are all watching the secondary market at the same time. They’re all trying to make a decision of how to fix this problem. Meanwhile, retailers are tired of seeing those bottles purchased in their store and taken to the secondary market to be sold for 50-200% more, so they’re increasingly saying ‘screw it, I’m going to start pricing like it’s the secondary market.’”

If you’re wondering why the distilleries don’t just step in at this point and say “Hey, don’t mark our product up by 500%,” it’s because they legally can’t. Although distributors are effectively able to set minimum pricing, the distilleries are legally barred in the U.S. from setting any kind of maximum pricing, thanks to the three-tier system that separates distilleries, distributors and retailers. Nor can distillers realistically attempt to punish those package stores that choose to gouge by threatening to withhold their products in the future, because they’re selling to large distributors rather than the stores themselves—and each distributor likely supplies hundreds of stores, further complicating matters. This can be as frustrating for the distilleries as you would no doubt assume—although a rabid fandom is undoubtedly a good thing when it comes to the health of a company like Buffalo Trace, seeing package stores gouging consumers for your products is less than ideal for the company’s image, if it makes customers resent the brand. I reached out to Buffalo Trace for comment, and received the following statement back, from spokesperson Amy Preske:

We are in the middle of investing $1.2 billion in expanding capacity, and we are currently making and shipping record amounts of whiskey, so we are pleased to be bringing additional amounts to consumers as we continue to try and catch up to demand, it just takes a while to wait for the aging process! We remain committed to selling to our distributors and the government operated markets at prices that allow their retailers to purchase and sell for our MRSP while making a fair profit. We are pleased to see the number of retailers that do sell at our MSRPs and have developed innovative and fair methods of distributing limited stocks such as raffles and lotteries. We understand the difficulties these retailers face given that supplies do not come close to matching demand, with no way for us to rapidly expand supply of available stocks. Given the regulatory and legal structure of the three-tier alcohol distribution system in the U.S., we are not in a position to comment on retailers who adopt a different approach to their pricing since we do not have a direct business relationship.

Ultimately, then, this sort of situation might not benefit a distillery such as Buffalo Trace as much as the consumer might assume—although it’s hard to say if the same would be true about a parent company such as Sazerac Co. If the current, hype-fueled buying climate incentivizes package stores to buy as much cheap, Sazerac-owned vodka and gin from their distributors as they can, in order to get access to some premium Weller or Pappy bourbons from Buffalo Trace to be sold at extreme, profit-generating mark-ups, then the ultimate effect of such hype would be a boost to the parent company’s bottom line. They’re able to sell more cheap bulk brands to distributors, who force package stores to buy those cheap brands for access to premium whiskey bottles, and the store makes its profit by massively marking up those bottles. Everyone benefits … except the consumer.

Being as massively popular as Buffalo Trace presents its own set of PR challenges for the distillery.

Being as massively popular as Buffalo Trace presents its own set of PR challenges for the distillery.

Prominent whiskey YouTuber Jason Callori, meanwhile, lives in the state-controlled liquor market of Ohio, and is thus able to get bottles (when available) for around MSRP, but has nonetheless observed the same bleed of secondary pricing into retail shops in other states. He expressed some frustration at trying to shop for whiskey during his travels through the U.S., saying “If shops need to mark things up somewhat, I get it, but they’re still buying these bottles at cost—they’d still be making a profit selling it at a basic mark-up rather than an extreme mark-up.”

“When a new product hits the market, you can see the same process unfold,” he continued. “The first person who gets a bottle sets it at a premium price on the secondary market, usually very high. They’re trying to set the market, to see if they get any bites. The difference with online package stores in particular, though, is that they’ll observe those secondary prices and then just keep their price that high until someone buys it. There’s no alteration or fluidity in their pricing, it’s just a statement: ‘This is going to sit here and collect dust until someone buys it.’ It drives me nuts to visit those types of stores. I think I accepted it when I first got into the whiskey game, but to see how far it’s gone, and the pricing that people are still willing to pay, it boggles the mind.”

What Callori describes has become the name of the game for many stores: Set something rare at a truly ridiculous price, ranging from 500% to 1000% mark-up from MSRP, and just play the waiting game. Physical stores may keep these bottles displayed behind the counter, or behind glass, secure in their confidence that eventually, a big enough fool will come along to pay any asking price.

The response of more rational whiskey geeks, meanwhile, might be to tell other consumers that they shouldn’t set a precedent by paying outrageous prices on the secondary market, but can you really tell consumers that when the same pricing comes directly to store shelves? When the ONLY way that these consumers are able to buy the product is by paying secondary prices, they’re left with severely limited options.

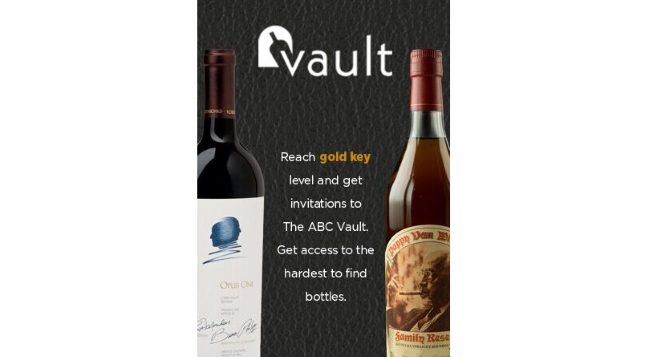

Other package stores and chains, meanwhile, have come up with more clever ways to profit off bourbon hype/mania than simply selling bottles for five times their MSRPs. In Florida, a large chain called ABC Fine Wine & Spirits (confusingly named, as it is not state operated) with more than 100 locations has found a truly creative, different way to gouge. They sell all brands of bourbon at MSRP, but anything that is the least bit desired—including essentially the entire Buffalo Trace lineup, of course—are all set aside into ABC’s “Vault” program, where they can only be purchased by members of the chain’s rewards program who have “Gold Key” access. How do you earn Gold Key access, you ask? By spending at least $500 at ABC in any given year, that’s how. So effectively, you earn the right to purchase a $30-50 bottle of bourbon at MSRP by spending at least $500 previously.

Reach platinum key status, and we’ll let you press your face up against the glass case where we keep the Pappy Van Winkle!

Reach platinum key status, and we’ll let you press your face up against the glass case where we keep the Pappy Van Winkle!

Wait, did we say “the right to purchase”? What I meant to type was you earn the right to maybe purchase those whiskeys, depending on what may or may not be available, with no guarantee at all that you’ll get what you’re after even after you drop half a grand to access the Vault. To soften the blow, Gold Key access also comes with a variety of other perks, freebies and discounts, but the Vault is clearly the point of the endeavor. As the liquor chain puts it:

The program was set up to give more people a fair shot at getting a bottle and to reward guests. Access members who reach Gold key level are eligible for at least one invitation to purchase from the Vault. An invitation to the Vault does not guarantee a purchase. There is a very limited quantity of every item sold in the Vault, so products are sold on a first come, first served basis. Members who receive an invitation may purchase one bottle from the available selection while supplies last.

And because points on customer accounts are cleared every year, this presumably guarantees the ABC chain a sudden, massive influx of spending in January/February as customers try to earn their Gold Key access back, in order to be among the first to access the Vault in the new year. It’s a system that allows the chain to claim “we sell at MSRP!” while simultaneously demanding at least $500 in compensation from each customer before giving them access to the products that people want most. Truly, it’s a brilliant innovation.

By the way—before you say that a product like W.L. Weller 12 Year should be priced by retailers at $250 or $300 because it’s a 12-year-old, sought-after bourbon in the modern bourbon market, consider the many well-aged, comparable bourbons that are regularly available for far less. Elijah Craig Barrel Proof is 12 years old and often as high as 130 proof, but is still regularly available for less than $80. You can get a 12-year-old bourbon straight from MGP in their Remus lineup for the same price. Likewise with Knob Creek 12 Year Old, which is only $60. Hell, Wild Turkey has Russell’s Reserve Single Barrel, with at least a 10 year age statement and 110 proof, for $60 as well. Every one of those has a proof point significantly higher than the 90 proof of the W.L. Weller, and many regularly defeat it in blind tastings. So think about that, before you try to justify that kind of pricing.

![]()

Whiskey Experts Respond: What Can We Do About Runaway Gouging?

Speaking in more depth with Jason Callori and Fred Minnick, each expressed similar thoughts on several tangents: The hype on certain brands has gotten out of control, and the consumers are the ones who wield the only real power in terms of reversing these trends.

Callori, on his Mash and Drum YouTube channel, recently posted a video on “overhyped and overpriced” bourbons, taking square aim at numerous brands such as Blanton’s and W.L. Weller that have been especially likely to draw retailer gouging. Specifically, he was inspired to put together the video after an incident he witnessed in person at an Ohio package store, involving a customer who really wanted his weekly allotment of Blanton’s, ultimately “throwing an absolute fit” and cursing store employees because the unloading of a shipment of the bourbon was late. Said Callori: “I was sitting there watching this grown man have a tantrum because he couldn’t get one brand, and that kind of put me over the edge.”

“This video was really targeted at store owners, people on the secondary market and people who are paying over-the-top prices for whiskeys,” he continued. “In some cases it may be because people are fairly new to it, but I see guys who buy some of these bottles and think they’re drinking rare unicorn tears, and that’s just not the case.”

Callori went on to say that he has some empathy for package store owners, who are often made to buy vast amounts of cheap, bottom-shelf liquor from their distributors in exchange for the right to buy a few sought-after, allocated bottles, but that still doesn’t justify marking those bottles up by 200-500% in his mind. According to this whiskey critic, only the consumers have any real power.

“I think that ultimately, the real issue is with us as consumers,” Callori said. “Until these guys stop buying these bottles at ridiculous prices, I don’t know when it will ever stop. I was in New York recently and stopped at a package store to see what prices would be like, there they were selling Old Rip Van Winkle for $700, and Weller C.Y.P.B. for $650 or $700. So I just sort of laughed and shrugged, because I’m never going to pay that, but I’m sure someone will eventually come along who will.”

Minnick likewise agrees that the situation feels like it’s gotten out of hand, “making everyone look bad,” from the distilleries, to the distributors, to the retailers and buyers lining up to be gouged. In particular, he believes more focus should be on the distributors and the consumers for the roles they play.

“The people who get a pass in this conversation are usually the distributors, when we should probably look at them closer,” Minnick said. “The distributors have allowed these kinds of mark-ups to happen. They do have the power to dictate where things are sold. If a retailer is selling a bottle at 400% over MSRP, I think the distributor should have a serious conversation with that retailer about how badly he wants some of this allocated stuff in his portfolio. But it gets dicey, because the retailer can counter by saying ‘well you’re only giving me one or two bottles, what am I supposed to do? I’ve got to make money.’ It all feels a bit absurd.”

On the positive side, Minnick points toward the emergence of new brands in the last few years that aim to deliver both value and quality, citing examples such as Heaven Hill’s Elijah Craig Rye, or Jim Beam’s recent unfiltered bourbon Old Tub. These affordable line extensions have helped to beef up the mid-shelf somewhat, but when push comes to shove, Minnick’s biggest advice to bourbon devotees is simply to refuse to pay absurd premiums for whiskey.

“I think we all have at least a little bit of blame here,” he said. “The best thing you can do as a consumer is honestly just not to follow the hype train. I can tell you that something like Blanton’s is a good bourbon, but it’s NOT freaking $200 good, and people should not pay that from a retailer. And I know that when I say something is good in a review, it means that others will go out and try to get that whiskey, but I try to also stress that I’m just one taster. I recommend that everyone figure out what they personally like—find your own flavor profile rather than seeking out what everyone else is chasing. But that’s going to take a psychological change in our country, because unfortunately that’s not how we operate.”

![]()

A Retailer Price Gouging Case Study

Finally, to illustrate what this sort of retailer pricing looks like on the ground level, I will present a case study of a single package store. This store was chosen not to shame a single, specific establishment, but to illustrate from top to bottom the way business is currently being conducted at many similar stores, with full-on secondary market pricing becoming the norm on store shelves. These prices are all readily available via the store’s website, as is the publicly available price list of the store’s distributor, which clearly states the legal minimum pricing of these brands, but obviously no maximum. That leaves the store free to charge whatever they will.

The point is: This store is not an exception, not in any way, shape or form. In fact, when I contacted the store, they made it clear that they’re only doing what they see other stores doing.

The store: Woods Wholesale Wine, a popular boutique wine and spirits shop in the affluent Detroit, Michigan suburb of Grosse Pointe Woods. All of these prices can be confirmed via Woods Wholesale Wine’s website.

— W.L. Weller Special Reserve: $99, which is 400% the MSRP.

— Blanton’s Single Barrel Bourbon: $214, which is a bit more than 300% the MSRP, although you can also pay an incredible $200 for a half-sized 375 ml bottle of Blanton’s instead.

For $14 less than the 750 ml bottle, you can buy … half the whiskey! Woo!

For $14 less than the 750 ml bottle, you can buy … half the whiskey! Woo!

— W.L. Weller 12 Year: $299, which is 600% the MSRP.

— Elmer T. Lee: $349, which is 875% the MSRP.

— George T. Stagg: $700, which is 700% the MSRP, and well above even secondary market prices.

— William Larue Weller: $900, which is 900% the MSRP.

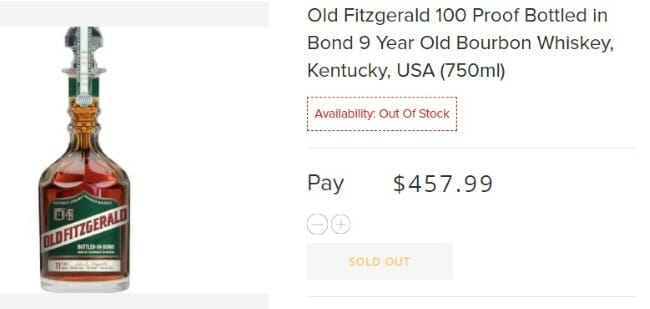

— Old Fitzgerald 9 Year: $458, which is 450% the MSRP.

It’s definitely not just Buffalo Trace products commanding these absurd prices.

It’s definitely not just Buffalo Trace products commanding these absurd prices.

— Old Forester Birthday Bourbon: $600, which is roughly 460% the MSRP.

This is just a general sampling of the types of mark-ups we’re talking about here, and although you could argue that this sort of package store is meant to cater exclusively to affluent suburban clientele, that fact that it’s selling these bottles online (the W.L. Weller SR and Elmer T. Lee are available now, if you’ll pay the price) means that they know exactly who they’re ultimately catering to—the inveterate bourbon geek who is willing to pay any price for hype.

Wanting to confirm these prices, I called Woods Wholesale Wine on the phone and spoke with an unnamed employee behind the counter. They confirmed the prices were accurate, and said the following when I asked how they justified charging 500% or more above MSRP: “We’re just going off what else is out there, available online. We sell every single bottle we offer at those prices. That’s what people are spending on those items.”

I then placed a call to Michigan’s Republic National Distributing Company, who serves as the primary spirits distributor to Woods Wholesale Wine. I already knew what I was going to be told, but I wanted to hear it directly from someone else’s mouth: Is the distributor fine with their package store account marking up so many brands more than 500% from the distributor’s publicly available price book? The answers were as expected.

“My company has nothing to do with the prices,” said an RNDC employee I spoke with about the situation. “We sell everything to our customers at a level that they can make a profit when pricing them at the state minimum, but obviously there are some people that charge a few dollars more, with whatever prices they have. It’s not something that my company has any control over. We can suggest all these things to our customers, but if they don’t listen to us, what can we do then? Sometimes people are willing to pay those prices, because they think those items are special.”

And that’s really the crux of this whole issue: No one entity is going to take responsibility for bourbon price gouging, so it’s ultimately on us, the consumers, to do something about it. The retailers will disavow responsibility, saying they’re only matching what other retailers are doing. The distributors will likewise disavow responsibility for how retailers are operating. The distilleries are legally unable to intervene. At each level, the response is the same: “We have no control.”

Whether or not that’s true almost doesn’t matter. The one group that does possess true control is the consumer, and this entire system is predicated upon the idea that we’re all so desperate for the latest hyped bottles that we’ll pay any absurd amount for them. What conclusion can you draw, other than the fact that we have to stop enabling the system that is increasingly taking advantage of us?

And so, as both Fred Minnick and Jason Callori earlier suggested, there’s really only one course of action: Stop paying vastly inflated prices from your neighborhood package store. Try some new brands. Give up on the hype cycle. Find some good values that you appreciate, and let others chase after bottles with 500% mark-ups from MSRP until such time as the hype finally dies down, bringing prices back down to earth with it. For what it’s worth, history suggests that the demand empowering such ridiculous pricing won’t last forever, and that balance will eventually be restored. Until then, perhaps we’ll just have to do without that W.L. Weller, and somehow find a way to go on.

Jim Vorel is a Paste staff writer and resident liquor geek. You can follow him on Twitter for more drink writing.