Each recipe is a story or a “condensed chronicle,” as Nigella Lawson wistfully says. Many of these stories proffer such riches of instructive, embodied knowledge that they have embedded themselves into infinite households.

Some stories are now so removed from their origins that they have taken on folkloric mysticism, their individual layers of penmanship—the adaptations, the tinkering with, the additional pinches of salt here and there—are no longer distinguishable. They dissolve into a milky brew of communality.

The chef and writer Rebecca May Johnson talks about meals as composition—the combination of ingredients becoming more than the sum of their parts. It is through this magical transformation we can conjure up times now bygone: our grandmother tenderly nursing a pot over the stove, our mother sharing tidbits of advice as we became newly independent at university, all the way back to ancestors who cooked and ate millennia ago.

In that sense, food becomes a means of communication in moments where words, sentiment and profoundness may otherwise escape us.

This may be particularly true where written language is literally absent. Historically, the Romani language didn’t exist in written form. The lineage of Romani Gypsies in the UK is varied and complicated, but they are thought to have begun their migration across Europe upon leaving North India around the 12th century. A combination of persecution and a preference for nomadic living kept them on the move until recent history when many have been assimilated into British society.

Despite having lived in Britain since 1515, there is little statistical information about Roma people: The category “Roma” was in fact only added to the census last year, meaning there is much work to unflatten some of the cultural distinctions that have otherwise been all but been erased.

Gypsies, Roma and Travellers (GRT) may not be overtly persecuted today, but a culture of anti-Gypsyism is still rife and, for the most part, unchecked. The recent Jimmy Carr joke about the Holocaust and the imminent Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, which will effectively criminalize nomadic living, are part and parcel of what has been termed the last “acceptable” form of racism.

I spoke to Ruth, a youth worker in Brighton who is on a personal journey to rediscover her Roma roots. When she was 12 years old, Ruth’s grandad was dying of lung cancer. He decided to finally disclose his—and subsequently the wider family’s—identity as Romani Gypsy, which he had felt the need to hide all of his life.

Since then, Ruth and her mum have been “working backwards to go forward,” making sense of clues dotted throughout their lives that together become a map of who they really are. Ruth has taken steps to reconnect with the Roma community, which she describes as giving her the feeling of “coming home.” Through the loss of her grandad, she has gained a wider family, one that reflects back “his humor and ways of respecting and treating others.”

Taking a cue from one of her earliest memories of her grandad cooking toast over an open fire (as well as his brylcreemed hair), Ruth is also finding her way back through food.

“Cooking is one of the last vestiges of our culture. When we think of resistance, it isn’t just the picking up of weapons or fighting. It’s the survival of things like recipes and the telling of stories. You can do what you want to erase someone’s way of life, but you can’t control how someone cooks,” she says.

This viewpoint in itself is not unique. The chef and author Claudia Roden, for instance, has often spoken about the ways Jews who were forced to leave Egypt after the Suez Crisis in 1956 wrote down and shared recipes. They became a thread between and in time, a glue to reconstitute the scattered “mosaic of families from the Old Ottoman Empire and around the Mediterranean.”

In the podcast series The Romani Tea Room, Nicoleta Calin describes the ways Romani food showcase “adaptation, travel, resilience and hardship.” Romani food all over the world shares core tenets, varying according to the particular seasonal and social contexts they became embedded in. Recipes are likewise often simple because of economic restraints and access to resources but are always hearty, generous and sustaining.

These foods include bountiful portions of stews with herby dumplings that use up available vegetables and meat that would once have been cooked in cauldrons over open fires. “Rib-sticking foods,” as Ruth calls them, like suet bacon pudding, which you “wrap in a clean tea towel and cook up the next day too” are also common. Rabbit pie and jam roly-poly pudding are other popular dishes.

Ruth wonders whether Gypsies’ ability to be self-sufficient—in skills of foraging, hunting and making do on relatively little—is one of the reasons why they have been seen as such a threat to society.

“You don’t have to pay a penny to cook with the nettles and wild garlic you pick, for instance. And that’s a threat because where does capitalism go?”

Ruth and her husband love foraging for mushrooms. They also make wine out of whatever is in season, like rhubarb and plums. They’ve even made mead from cherry blossom: “It was really good, although admittedly, it can get quite pokey!”

Nanna Varey, a Romani woman and one of the administrators of the Facebook group Traveller and Gypsy Recipes and Tips agrees: “There’s an old Gypsy saying that when you carry your own water, you appreciate every drop of it. And that is absolutely true.”

Some of Nanna’s fondest memories of childhood took place around the dinner table.

“We lived by the sea, so my dad was always putting lines out and we were always eating fish. Unless we were lucky and he’d caught a rabbit!”

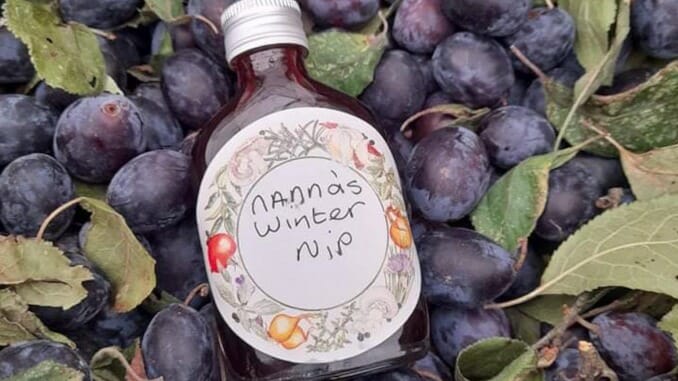

Now Nanna gleefully cherishes time spent with her grandchildren collecting blackberries, reliving “magical” moments spent with her own mother. Amidst her creations of homemade pasta, cheese and liver and onion, she is first and foremost a jam connoisseur.

“You can’t have a worry on your mind when you’re making jam because you’ve got to concentrate. There’s a fine line between jam and toffee, after all! Even if you haven’t done all your chores or you’re feeling anxious, you can always stand back and look at what you have made.”

It is here that cooking derives a magical quality. The kitchen becomes a microscopic world where it’s possible to fashion sweetness from chaos and produce something tangible to show for our efforts. Everyday hardships can be distilled, bottled up and transformed into little jars of cloudy pink and sugary damson.

For SarahJane, who identifies as an English Gypsy, food is the greatest language of love.

“I haven’t personally got a sweet tooth, but I absolutely love making cakes. For my son’s thirty-third birthday, I made a chocolate cake with Tyson Fury’s face on it! He was chuffed. And said it was delicious too!”

It all began when she cunningly avoided going to church as a little girl by offering to stay behind to cook the Sunday meal. She never looked back. The community built around food and mealtimes has been literally-life saving for SarahJane. After her husband died two years ago, having been together for forty years since they married at sixteen, she went about creating her own antidote to the newfound loneliness. She set up the “Gypsy and Gorger [non-Gypsy person] Chit Chat” group where people who might otherwise be struggling come together for support.

“There’s one girl who was so anxious she was practically silent on it for all of six months. Now, she’s the first person on it in the morning, sharing funny posts all day long, thriving. She’s told me it saved her life.”

SarahJane beams with pride whilst exclaiming, “I’ve even got stickers with ‘I’m a Gypsy!’ all over my van! Being a Gypsy teaches you to always make the best of any situation. Truthfully, I do worry about how I’ll afford to keep feeding myself sometimes, but I’ll never stop giving to others.”

Ruth observes that in the face of forced Gypsy assimilation, the Facebook groups become another archive of history.

“I’ve learned so much from these groups. All recipes seem to start with an oxo cube! People call each other Aunty, Uncle or Cousin—it’s really heart-warming.”

SarahJanes’ cakes, Nanna’s jam and Ruth’s mead are also part of this rebuilding of Romani culture that has otherwise been stamped out of history. The sharing of recipes, the practice of living off the land and the joy of a steaming bowl of joe grey, a traditional Romani stew, are small but potent and delicious acts of resistance. They are the making and re-making of the Romani people.

You can find Nanna’s recipe for damson jam in the Traveller and Gypsy Recipes and Tips cookbook.

Ruth and her husband’s recipe for bacon pudding:

200 g self-rising flour

125 g suet

120 ml water

1 large onion

Fresh thyme

1 pack of smokey bacon

1. Mix the flour, water and suet together with a pinch of salt to make a dough before rolling it out into a rectangle.

2. Cover with a layer of chopped onion, the smokey bacon, a good screw of pepper and plenty of chopped thyme.

3. Roll up like a Swiss roll and seal the edges with water. Wrap it tightly in a pudding cloth with the ends tied tightly or wrapped in a good amount of cling film and boil for 2.5 hours. Keep topping up the water when needed.