When we discuss the different types of videogames on the market, many genres come to mind. Bullet hell, platformer, role-playing, first person shooter: these terms summarize a type of gameplay and tell us what to expect from its mechanics. But what makes a comedy game? In a medium that often defines itself by what it does and not what it says, it’s hard to establish criteria for a category that traditionally (in other formats, like film or literature) is delivered mostly through narrative and dialogue. A game like Portal 2, for example, may not be considered comedy mechanically, but it has characters like Wheatley and GLaDOS that carry the game’s sense of humor through their spoken lines. Would a game like Portal 2 be considered a comedy game, or is it a physics platformer that just happens to be funny? Does the distinction even matter if the definition includes both?

Three recent titles demonstrate how comedy can be cultivated within the confines of a subjective interactive experience. The Elizabethan spoof Astrologaster is a dramatic irony comedy, where the audience has an omniscient understanding of the events, and finds humor in the failures of the characters. What The Golf, a goofy physics game, is a subversion comedy, using a break in the player’s expectations to make them laugh. And Untitled Goose Game is straight-forward slapstick, relying on comic mischief and situational humor. For the developers of these titles, the paths to amusing their audience were disparate, but ultimately reached the same destination.

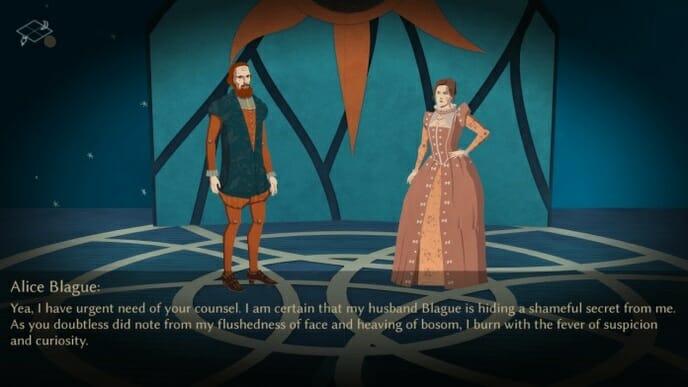

The opportunity to write from a place of personal amusement was a rare one for Astrologaster writer Katharine Neil. Game director and designer Jennifer Schneidereit, who was responsible for the game’s premise, approached Neil on the basis of her previous work in comedy games, as well as her sense of humor. A parodic take on the life of the 16th century physician Simon Forman, Neil was brought in on the game to write within the joke telling framework established by the game’s basis. “For me it was very much about approaching it from the outset as a comedy project, rather than developing a story and livening it up later with humorous dialogue. My job was to sort of ‘mine’ a large amount of historical material for comedy, and work out which comedic devices would work with the gameplay and the material.”

Schneidereit and Neil’s approach, rather than creating a set of dialogue trees that would essentially deliver funny lines directly into the player character’s mouth, was to mediate the player’s choice by the game’s astrology. This, she explains, introduced friction into the player’s decision making process, but also an element of surprise that was similar to the structure of a joke. “First, the player chooses the joke’s set up (a pastor, a priest and a rabbi walk into a bar etc.—but in our case it’s more like Mercury, Venus and Aquarius walk into a bar), then Doctor Forman combines those elements to reveal and deliver a punchline.”

Many, if not most, games offer an element of skill-based challenge. Often, the trick of that challenge is why the game exists; against the chance of failure, the player’s goal is to prevail and succeed. Astrologaster is unique in that the guesswork in Simon Forman’s astrology-based method of diagnosing his patients is meant to illustrate the incompetence of medieval medicine. “Failure” (or, rather, intuiting the correct answer through other means, like conversational clues) is not just a part of the game, it’s kind of the point.

Supplementing the ineptitude of Doctor Forman and the scandalous goings-on of his noble patients are the choral interludes between chapters, each written and sung in verse, showcasing the game’s unmerciful observations about each character’s predicament. Neil also peppered the dialogue with in-jokes and obscure references, offering additional depth and a range of surprising but satisfying outcomes. “Some [streamers] seem to get into how the astrology works and pick up on the clues, and some just play it casually. We were aiming for both styles. I was surprised how what the player seems to ‘get’ (in terms of jokes, hints, subtext, historical references) varies between players. So it made me think oh ok, so no element, no matter how obscure or tiny or subtle or buried in the subtext, is wasted. Even if there’s only one player in the world who gets a certain element, that satisfies me.”

What the Golf also tackled comedy in the pursuit of self amusement but from a different place: boredom. According to creative director Tim Garbos, the team started the game as a “Dark Souls-inspired rogue-like-golf” and went through several versions before they realized that in order to make the sport interesting, it was going to require a complete subversion of expectations. As he told Gamasutra, “If you repeat a thing enough times, people start expecting the thing to happen. That’s when you do the other thing.” From this simple concept, the team began to see golf mechanics everywhere in the world around them, developing the game’s outrageous ragdoll physics and silly level themes in parallel along the way. Talking to Paste, Garbos says, “The first couple of iterations [of the game] were way less funny and had less focus on comedy. But once we made a few fun things we just couldn’t stop.” They began by building levels where the player golfs with something other than the golf ball (“I believe the very non-ball thing we golfed was a park bench and a couch”), with wordplay ultimately playing a major role. “We did a lot of brainstorms trying to come up with a pun based levels as well. Like a tiger you golf through a forest, Tiger Woods, etc. We made a lot of levels that didn’t make the cut, so we probably cut off more than half the levels to find the ones that really worked.” The result is a mini putt putt course of the absurd, a place where the golf ball never acts the way you think it will, if it’s even a golf ball at all. The ragdoll physics, whether they’re launching your golf club or your golfer themselves across the screen, fit neatly within the game’s desire to subvert expectation.

One of the better parts of demoing What the Golf in its early days was the simplicity of the build: the levels came in a bite sized barrage that let the player enjoy them before their gimmick had a chance to go stale. The addition of the campaign mode, which brought in a little mini golf course and a neat, neo-chic office aesthetic to hold the levels together, provided a cool contrast to the silliness of the game. This is on purpose, Garbos says, “making everything very clear. For slapstick comedy to clearly translate, especially on a small screen, it needs to be easy to read”—a fun choice of words, given how little text is actually used in What the Golf. The puns are among the only words that appear on screen, but the reticency works to the game’s advantage. It provides a contrast to the wacky physics that works similar to pantomime.

Ultimately those same physics make the case that technology alone, without the additional context provided by written dialogue or narrative, can touch on the classic frameworks of comedy. Puns informed the creation of each level, but how the ball or club (or in many cases, the alternate item assigned that role) physically respond to touch is where the objective-based challenge lies. In that sense, What the Golf demonstrates that some forms of comedy may even be unique to games alone.

Like What the Golf, the majority of the Untitled Goose Game’s humor is delivered without text or narrative. It’s almost a situational comedy, in that the premise of the game is the jumping point for its humor. It stars an animal who lacks both opposable thumbs and sophisticated speech but somehow still manages to terrorize an entire village in the pursuit of love. It’s funny before the game can even begin.

Developed by House House, a team of four friends, the process of designing Untitled Goose Game involved a lot of open collaboration. The goal was mostly to make themselves and each other laugh. Together they created both the means and the scenarios for the titular goose to act out, choosing their villainous protagonist based on the universally aggressive experiences people have had with geese—though not any personal experience of their own. Says House House’s Stuart Gillespie-Cook, “We were very lucky to stumble onto this thing that had such concrete associations for so many people. For us, it was more about this kind of mythical status a goose has. We loved the idea of an animal that is universally accepted as ‘naughty’.”

For a game that was so funny, the response to it was even funnier: few have inspired so many adoring memes on social media, especially for a game that’s so short. In many ways, the community surrounding Untitled Goose Game gave it new life outside of the developers’ original intent. Fans fiddled with the game’s boundaries and extended the gameplay by creating new self-imposed challenges, like one person who collected every single item in the game, taking on a quality that almost seems as collaborative as the original design process itself.

This two-way street sort of interaction, facilitated by the inherently interactive nature of games, gives the game an almost conversational quality. But Gillespie-Cook says that for them, it’s less about how players subvert the intentions of their design, and more about how certain jokes and set-ups find new life in fresh hands. “When people do things with the game totally outside our expectations, like using all kinds of exploits to finish the game in two and a half minutes, or using certain objects to fly around the map, it feels very special, and is super fun for us to watch. It doesn’t really feel conversational though. It’s less like they’re riffing on a shared concept and more like they’re just making the game their own.

“That conversational quality for me is in quieter moments. Even after hours and hours spent watching people play the game, I still regularly laugh out loud while watching someone performing the exact same joke I’ve seen hundreds of times before, despite the fact that we put that exact situation in the game. They make some tiny tweak to timing, or the body language of the goose, and I find it funny all over again.”

One of the challenges of designing a “funny” game is that the interactivity makes the audience’s participation levels unpredictable. It’s almost impossible to anticipate every possible variable influencing a player’s behavior, which makes it difficult to make a joke interactive. Gillespie-Cook says that addressing this meant relying on structures that the audience is already deeply familiar with. “The approach we settled on early is that for the most part the game is made up of these big, set-piece moments in which the setup and punchline are extremely obvious from the start. They’re all completely classic, timeless gags. We’ve had people ask us about our comedic influences, whether we were particularly into a particular silent-era movie star etc., but really these jokes are even more primal than that, it’s the stuff you’d see at a clown performance, or a pantomime or something. They’re completely engrained in the culture. So then enacting it becomes all about these little subtleties of movement or context, rather than directing the format of the joke. The player knows the beats of the script, and now they get to perform it.”

As these games demonstrate, there’s no single approach to designing a comedy game. Rather, the classic frameworks of comedy can be adapted to the medium in addition to those created organically by its own eccentricities. Perhaps more important than trying to establish the criteria for a genre (after all, what is a genre but a marketing device?) is what all three games have in common: the sincere desire to make people laugh. From that one design goal, so many techniques have evolved, be they mechanically based or driven by narrative. Maybe that’s the best punchline of all.

Holly Green is the assistant editor of Paste Games and a reporter and semiprofessional photographer. She is also the author of Fry Scores: An Unofficial Guide To Video Game Grub. You can find her work at Gamasutra, Polygon, Unwinnable, and other videogame news publications.