Final Fantasy X-2 was the end of something. The final game released by Squaresoft before the Enix merger, the final new entry to feature ATB combat, the final game with pre-rendered backgrounds, the final game made with Hironubu Sakaguchi’s involvement. The series had always been more loose and experimental with its traditions, the Pepsi to Dragon Quest’s Coke, but the new millennium would see the doors blown off. There had been a movie, there had been an MMO, and now, with the company merging in less than ideal circumstances, there would be even bigger changes on the way. Because although it was the end of something, Final Fantasy X-2 was also the beginning. It was the series’ first sequel.

20 years later, it’s still the best one they’ve ever made.

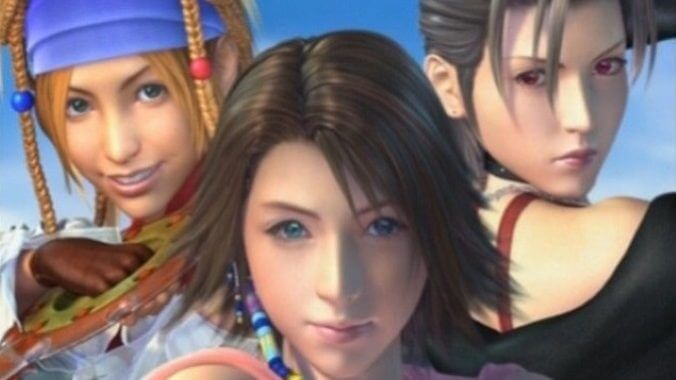

In the wake of X-2’s massive financial success for a relatively small development cost, it became the template for the series going forward. Square greenlit the compilation of Final Fantasy VII to capitalize on that game’s massive popularity. Final Fantasy XIII was announced alongside the entire doomed Fabula Nova Crystallis project, but ended up receiving lower budget sequels built, like X-2, around smart asset reuse. Final Fantasy XV was followed by a truckload of DLC that seemed to be attempting to retcon the entire game before it was unceremoniously, and somewhat hilariously, canceled. Uniting these projects is a particularly reactive sensibility in their creation; directly responding to fan complaints and demands. Vincent Valentine and Zack Fair are popular, underwritten characters, so they’re both getting a game. Fans disliked XIII’s linearity, so XIII-2 is a time traveling hub and spoke adventure. Hajime Tabata is going to make Mass Effect 3 look restrained. No one asked for J-Pop Yuna.

This is what gives X-2 such a polarizing reputation. To some, it is an unserious and disposable sequel that tarnishes and undoes the legacy of a classic game. To others (me), it is a masterpiece that continues the story of Final Fantasy X by asking seriously what happens next in a world where God is already dead, and refusing to blink by doing something stupid like, I dunno, bringing Sephiroth back 50 times.

Instead of a raising of the stakes and introducing a new terrifying threat that must be defeated, X-2’s plot is a patchwork of various character stories tied together by an undercurrent of political unrest. It is, unlike most JRPGs, and, indeed, fantasy stories in general, not a restorative fantasy. There is nothing to restore. You may have killed God and freed Spira from its constant torment by Sin, but the Eternal Calm is not victory. Something new must be built in the vacuum. The main plot of X-2 focuses on the conflict between the Youth League and New Yevon. The Youth League feel rightly betrayed by the teachings of Yevon that kept Spira in its cycle of destruction, but are quick to arm themselves with the very Machina that led to war in the first place. New Yevon want to hold onto the cultural traditions that have been central to Spira’s history for a thousand years, refusing to throw out the moral practice of their religion in day to day life even as its leaders were revealed to be corrupt.

But X-2 is not really a debate between two dogmatic factions, so much as these factions form the touchstones for each character’s perspective on the changing Spira. The road trip structure of the original’s solemn pilgrimage is replaced by the ability to travel around the world by airship immediately, completely re-contextualising a familiar world. Where before Spira was a lonely, quiet world of disparate villages separated by dangerous roads, now it is an overly crowded archipelago, bustling with different cultures and histories all with their own perspective and desire for the future. From the lost traditionalists of Besaid to the disgraced Guado fleeing their now vestigial home to—in the game’s most famous flourish—your uncle turning the holy land of Zanarkand into a kitschy tourist trap, it’s Yuna’s job to listen, and to find some path forward for everyone. Many Final Fantasies end with your main character as king of the land, leading the world into a new future with the darkness defeated, but X-2 is a game about the labor of leadership, the uniqueness of Yuna’s position and the burden on her to not run away, as much as she wants to be a normal girl again.

At its most extreme, X-2’s commitment to refusing the easy way out is somewhat of a thematic door slam on the franchise that the series struggles to move past, to this day. The game’s final act features its protagonist loudly stating that there is no silver bullet, there is no act of violence or sacrifice large enough to solve our problems. There is in reality no god to kill, and to invent one is turning your back on reality when you could be helping people. I don’t like your plan. It sucks.

It’s little wonder then that when revisiting X years later, instead of imagining more uncharted futures, scenario writer Nojima doubled down on the game’s most controversial and out of place plot point: bringing back Tidus. So much of the game is about Yuna moving on and finding a new sense of self outside of her role as a summoner, that to throw all that away in the true ending produces a sense of disquiet. To bring him back you even have to say “yes, I still want this” to an NPC explicitly asking you hey isn’t this against every lesson you’ve learned? The return of Tidus leads to the return of Sin, to a world unable to let go, to do nothing but retell the same stories again and again. The good ending for Spira is for Yuna to simply walk away from his ghost.

While the proposed X-3 did not (at the time) continue, these ideas instead led directly into Final Fantasy VII Remake, as we ask such tantalizing questions as will Aerith die this time? Will Zack replace Cloud and ruin the entire series? Will we really fight Sephiroth at the end of three games in a row? For as fun as Remake is—and to be clear, it’s great so far!—it’s hard not to look back at Final Fantasy X-2 and see a game too structurally ambitious, too tonally incongruent, too fucking annoying (I speak here of that damn monkey minigame) to be embraced as the masterpiece it is. While well reviewed and financially successful, X-2 has gone down not as the series’ creative zenith but as just another polarizing experiment, and unsurprisingly Final Fantasy’s future franchising efforts would tend towards playing the hits: We Still Don’t Know Sephiroth.

And I think it deserves better. Final Fantasy X-2 isn’t just a good game, it is a model of the series at its best, pushing the form and theme of classic JRPGs to their limits and finding something new. 20 years on, Yuna is still right. We have to move forward, or we will dream the monster back to life.

Jackson Tyler is an nb critic and podcaster at Abnormal Mapping. They’re always tweeting at @headfallsoff.